Other non-ferrous metal alloys

Although materials science most often refers to steels and alloys of aluminum and copper, many key technical applications are based on more specialized non-ferrous metal alloys. These alloys enable the design of friction joints with controlled wear, the creation of tight and durable soldered joints, the construction of safety elements that operate by melting, and the achievement of high corrosion resistance or an exceptionally favorable strength-to-weight ratio.

This study discusses six groups of materials: bearing alloys, soldering alloys, low-melting alloys, zinc and its alloys, titanium and its alloys, and precious metal alloys. The table shows how the choice of composition and microstructure translates into specific operational requirements: from lubrication and “running-in” to chemical resistance and retention of properties at elevated temperatures.

This article was based on the textbook “Metaloznawstwo” by Professor Stanisław Rudnik. The following content is only a general overview of the topic. For those interested in the subject, we highly recommend delving deeper into the literature.

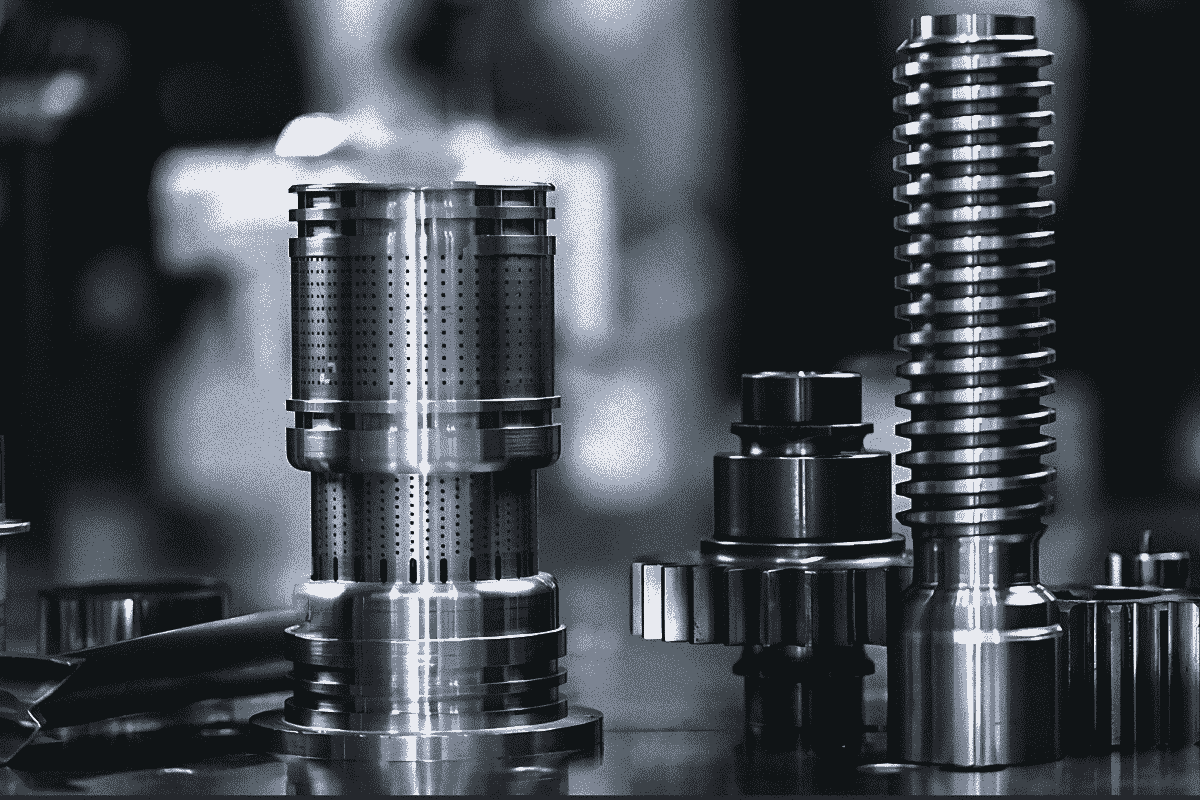

Bearing alloys

Bearing alloys are used to make bearing shells in sliding bearings, where the surface of the bearing shell interacts directly with the shaft journal. The bearing shell material must therefore ensure a low coefficient of friction, reduce wear on both rubbing surfaces, and at the same time withstand high unit pressures. It is very important that the bearing shell is less hard than the journal, so that any damage occurs in the element that is easier to replace, and not on the shaft. Scuffing resistance is also important: the bearing shell should be plastic enough to adapt to the micro-irregularities of the journal, but at the same time it must not be too soft so that it does not stick to the surface of the journal at operating temperature.

In practice, these requirements are complemented by technological and operational properties: the alloy should be easily meltable (to facilitate the casting of cups), but its melting point must not be too low, so that the cup does not soften when heated during operation. Other important factors include good adhesion of the alloy to the bearing shell material, adequate thermal conductivity (friction heat dissipation), corrosion resistance, and the lowest possible cost.

The best properties are obtained by an alloy with a structure in which hard inclusions of appropriate size and quantity are evenly distributed in a relatively soft and ductile matrix. The soft matrix facilitates adaptation to the shape of the journal without intense abrasion, while the hard components reduce the tendency of the matrix to adhere and promote the formation of capillary gaps in which a thin layer of lubricating oil can remain. The friction node then operates more stably, and lubrication conditions are easier to “maintain” even during temporary overloads.

The cheapest bearing material is often gray pearlitic cast iron. It can withstand high unit pressures, but due to its relatively high abrasion, it is not suitable for high-speed engines. The presence of graphite has a beneficial effect: crushed graphite mixed with grease forms a thin layer on the surface that reduces abrasion. However, in applications requiring better parameters, soft, easily meltable alloys based on tin or lead are most commonly used.

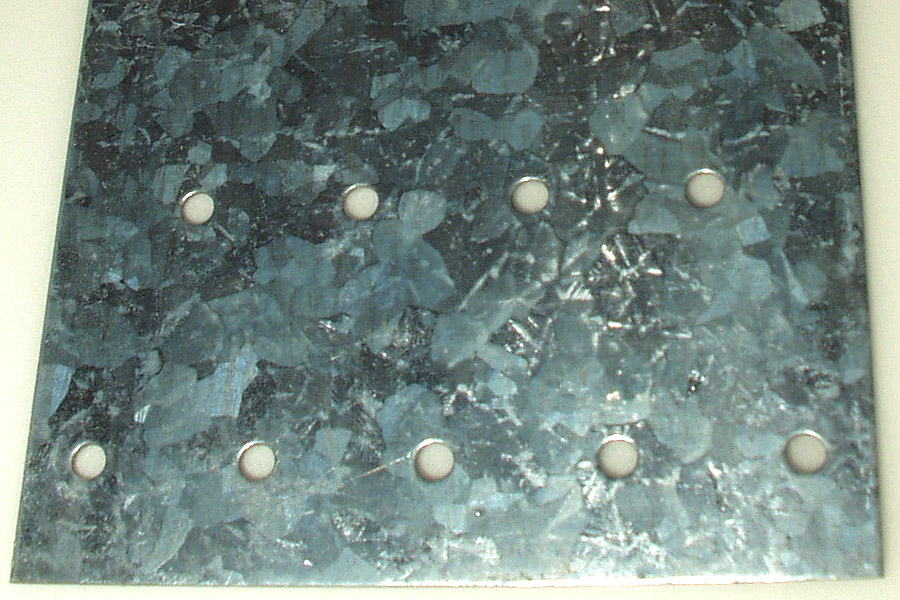

The best group of bearing alloys is tin-antimony-copper alloys, known as babbitt. Copper and antimony increase the strength of these alloys with a slight reduction in plasticity, so it is crucial to balance them. For the commonly found copper content of 3-6%, the highest strength is achieved at around 9-10% Sb, and compositions not exceeding 10-12% Sb and 6-7% Cu are considered particularly favorable. This group includes, among others, SnSb8Cu3 and SnSb11Cu6. The matrix is a solution of antimony and copper in tin – soft and ductile, although harder than pure tin – and against this background, there are cubic crystals of the SnSb compound and Cu6Sn5 crystals in the form of stars and needles. The hard phases act as load “carriers” and stabilize friction conditions, but babbits are expensive, so they are mainly used in bearings operating under high loads and speeds.

A cheaper alternative is tin-lead-antimony alloys, in which some of the tin is replaced by lead. The soft matrix in these alloys is a triple eutectic with a high lead content, and the structure still contains cubic SnSb crystals. In practice, copper is often added to reduce segregation resulting from differences in the density of the components; the copper then forms hard needle-shaped Cu2Sb compounds. An example is the PbSn16Sb16Cu2 alloy, which is cheaper than babbitt but usually operates in less demanding conditions (lower loads and speeds).

The third group consists of lead alloys with alkali metals such as calcium, barium, or strontium. These elements form hard compounds with lead (e.g., Pb3Ca, Pb3Ba) distributed in a soft matrix of almost pure lead; a small amount of sodium is also sometimes added to increase hardness. The advantage is low cost with good quality, which promotes wide use, especially in railways. The limitations include low resistance to atmospheric corrosion and the burning out of alloying elements during remelting. In bearings operating under particularly harsh conditions (high pressures and speeds), tin bronzes or lead bronzes are also used.

Solder alloys

Soldering is the process of joining metals using an additional metal – solder – which is melted, flows, and fills the joint gap. The melting point of the solder must be lower than the melting point of the metals being joined so as not to cause them to melt. A good solder should wet the soldered surfaces well, dissolve to a limited extent in the metals being joined, exhibit good fluidity in the liquid state, and its solidification range should not be too wide, as this makes it difficult to obtain a homogeneous, tight joint.

Due to their melting point, there are soft solders (up to 450°C) and hard solders (above 450°C). Soft solders have low hardness and low tensile strength (approximately 50-70 MPa), but they are ductile, which is why they provide good tightness, although they are not usually designed to carry heavy loads. The most common are tin-lead solders, in which an important reference point is the eutectic composition of 61.9% Sn and a melting point of 183°C.

Tin-lead solder is covered by the PN-76/M-69400 standard, and individual solders are marked with the letters LC and a number corresponding to the average tin content in percent. Variants with the addition of antimony have the letter “A” at the end of the designation, e.g., LC30A contains approximately 30% Sn, 68% Pb, and 2% Sb. Solder LC60 (60% Sn and 40% Pb) has a composition close to eutectic, so it is the most easily melted and has a very narrow solidification range of around 7°C. As the lead content increases, the solidification range increases; in a binder with 20% Sn and 80% Pb, it can exceed 100°C, which promotes the formation of pores and impairs the tightness and strength of the joint. At room temperature, the hardness and strength of Sn-Pb alloys increase with the tin content, and the highest values are usually obtained by alloys with 50-80% Sn; on the other hand, alloys with a very low tin content (5-10%) are less scarce but have poorer properties.

Hard solders work at much higher melting temperatures (from about 400°C up to 2000°C) and are used where high strength is required from the joint. The strength of joints made with hard solders can be around 200–700 MPa. In practice, there are three main groups: copper-based solders, silver-based solders, and special solders. Copper has good soldering properties and is used to join steel, cast iron, and copper alloys, but its high melting point requires soldering at temperatures of 1100–1200°C, which increases energy consumption and can impair the properties of the soldered components due to structural changes during heating. For this reason, in addition to pure copper, its alloys are widely used. Silver alloys (covered, among others, by PN-80/M-69411) are important in electrical engineering, among other fields, and the most significant are Ag-Cu-Zn alloys with good mechanical properties and corrosion resistance, allowing the joining of steel, copper alloys, precious metals, and sintered carbides. Special solders include, among others, gold and platinum-based solders (e.g., jewelry, dentistry), aluminum-based solders (joining light alloys), and magnesium-based solders (joining magnesium alloys).

Low-melting alloys

Low-melting alloys (easily melted) are alloys with a melting point lower than that of tin, i.e., below 232°C. They consist of metals with a low melting point, primarily lead, tin, and bismuth, as well as, in smaller quantities, cadmium, antimony, zinc, indium, and other additives. The composition is selected so that eutectics with the lowest possible melting point are formed, which allows the melting point of the fusible element to be precisely “set.”

A good illustration of the effect of multi-componentity is the Sn-Pb-Cd-Bi-In system, in which the eutectic alloy can have a melting point of around 47°C. In practice, the low-melting alloys used in our country are listed in the PN-71/H-87203 standard. Among the alloys listed in this standard, one of the lowest melting points (approximately 70°C) is that of the BiPb25Sn12Cd12 alloy, known as Wood’s alloy, with a composition of 25% Pb, 12% Sn, 12% Cd, and 51% Bi.

The applications result directly from the function: low-melting alloys are used for fuse links and safety inserts, fire and alarm system components, in precision casting, as well as in the medical equipment and orthopedic industry, where low process temperatures are often crucial for safety and precision.

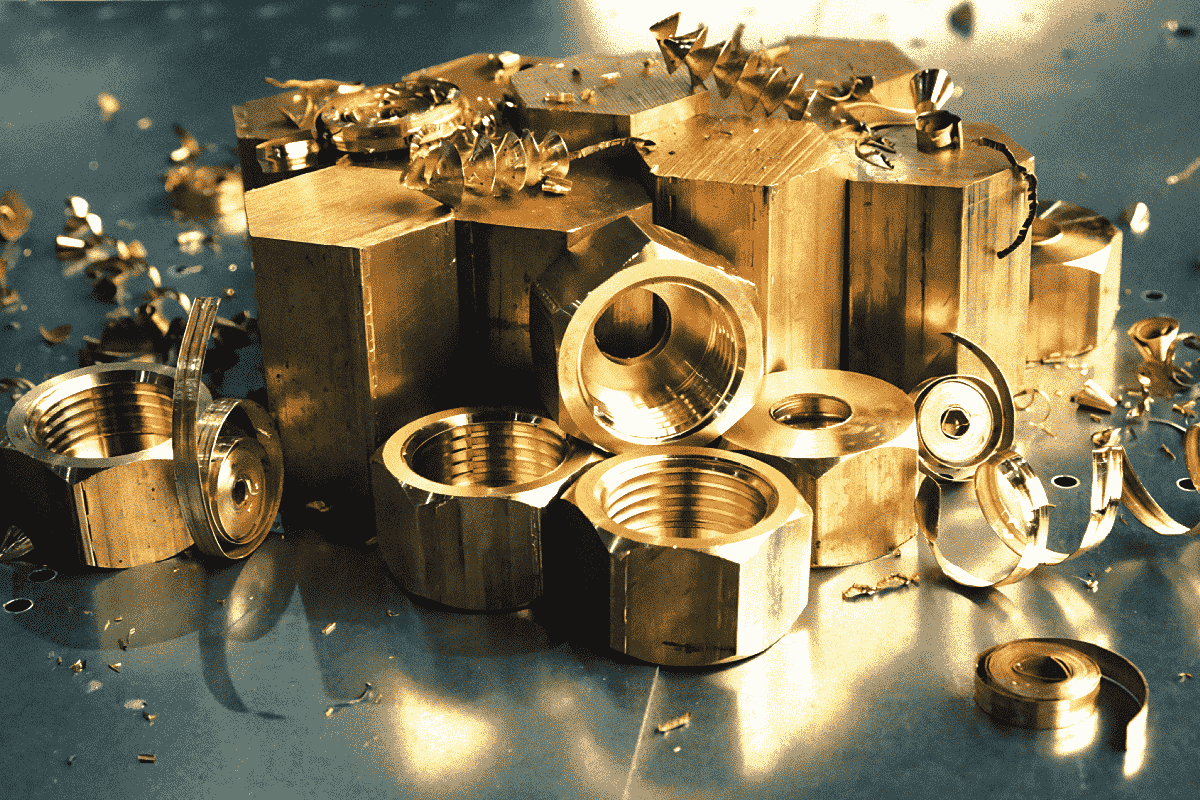

Zinc and its alloys

Zinc is a blue-white metal with a specific gravity of approximately 70 kN/m³. It has a low melting point (419.4°C) and boiling point (907°C). Its tensile strength is moderate (Rm approx. 150 MPa) with high elongation (A10 approx. 50%), but at room temperature, zinc is brittle. Only when heated above 100–150°C does it become malleable and can be rolled into thin sheets and drawn into wire.

Zinc is resistant to dry atmospheres, but in the presence of water vapor and carbon dioxide, it becomes covered with a white coating of alkaline zinc carbonate, which acts as a protective layer and limits further corrosion. Zinc dissolves in dilute acids and alkalis. The most important industrial use of zinc is in the protection of steel: zinc coatings (galvanizing) are beneficial because even with local leaks, zinc acts as a protective anode. Since it has a lower electrochemical potential than iron, zinc dissolves, and the steel is thus protected from corrosion.

Zinc is also used as a material for semi-finished products (e.g., in construction) and is an important component of many other metal alloys. There are a few alloys in which zinc is the main component, the most important being zinc alloys with aluminum, copper, and magnesium, known as znale. They are divided into casting alloys and wrought alloys. In addition to zinc, they usually contain up to 30% Al, up to 6% Cu, and small amounts of Mg; the differences between the varieties result from their intended use and manufacturing technology.

Wrought alloys achieve higher strength (approximately 280–320 MPa) with better plasticity (A5 approximately 5%). Casting alloys have a strength of 150–300 MPa, but very low plasticity (A5 approx. 1%), which is typical for castings, especially pressure castings. Despite their limited plasticity, cast zinc alloys are widely used in the machine industry (bodies, frames, covers), the automotive industry (carburetors, levers, door handles), and the electrical engineering industry (device housings). Plastically workable alloys can replace more expensive copper alloys when economy and simpler technology are important.

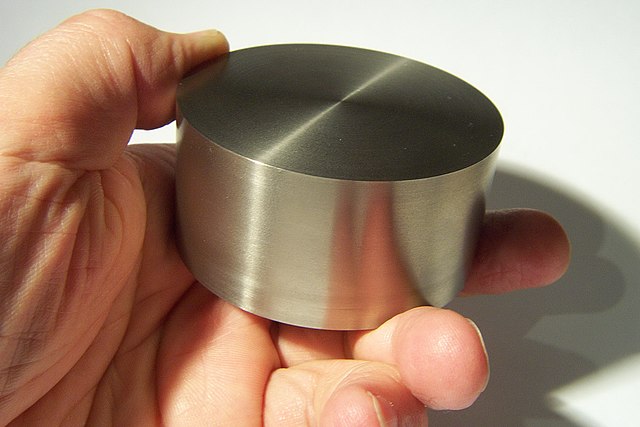

Titanium and its alloys

Titanium is one of the most abundant elements in the Earth’s crust, but its industrial production on a larger scale has only developed since 1948. It is a silvery-white metal, resembling stainless steel, with a low specific weight of about 44.1 kN/m³, which is almost half that of iron. This is why its strength-to-density ratio is particularly advantageous, which translates into applications where every kilogram counts.

Titanium occurs in two allotropic forms: Tiα (stable at low temperatures, compact hexagonal lattice) and Tiβ (stable at higher temperatures, spatially centered regular lattice). The allotropic transition temperature is 882°C. This material is characterized by very high corrosion resistance, comparable to that of austenitic chromium-nickel steels. At temperatures up to about 500°C, titanium is practically unaffected by air; only at higher temperatures does a thin, well-adhering layer of oxides and nitrides form on its surface, which protects the metal from the effects of oxygen and nitrogen, as long as the temperature does not exceed about 560°C. Above this range, the chemical activity of titanium increases significantly.

The mechanical properties of titanium depend heavily on its purity. Very pure titanium is extremely ductile and has parameters similar to those of pure iron: Rm approx. 250–300 MPa, R0.2 approx. 100–150 MPa, A10 approx. 50%, and Z approx. 70%. Additives increase strength at the expense of plasticity, which is why, in engineering practice, the purity and alloying class are selected according to requirements. Due to their corrosion resistance and high weight strength, titanium and its alloys are used in vehicles, aircraft, shipbuilding, and chemical equipment, although their high price remains a barrier.

In titanium alloys based on both allotropic varieties, there are solid solutions of α and β. Since the β phase is stable at high temperatures and the α phase at low temperatures, heat treatment based on phase transformations becomes possible. The mechanism of the β→α transformation depends on temperature: at higher temperatures it is diffusive and leads to a granular structure, while at significant supercooling – due to the low mobility of atoms – a non-diffusive martensitic transformation may occur, resulting in a needle-like (martensitic) structure often referred to as α’.

Titanium alloys used in practice are divided into single-phase α, single-phase β, and two-phase α+β alloys. α alloys include, among others, titanium alloys with aluminum, which is the only additive stabilizing the α phase; aluminum increases strength and, due to its low density, has a positive effect on the specific weight of the alloy. β alloys are relatively less common, while the most important are two-phase α+β alloys, containing additives that stabilize the β phase, such as vanadium, molybdenum, tin, iron, chromium, or magnesium. They are usually stronger than single-phase alloys, easily plastic-worked, and susceptible to heat treatment; typical Rm is around 900-1200 MPa, and in the temperature range up to 500°C, their strength per unit density is sometimes more favorable than for steel.

Although martensitic transformation suggests the possibility of classic hardening, in practice, it is not commonly used because the effect on mechanical properties is sometimes negligible. For α+β two-phase alloys, heat treatment typically involves supersaturation and aging: supersaturation involves heating to a temperature at which the β phase is stable, followed by rapid cooling to retain this structure. During aging, the β phase partially decomposes into an α+β mixture, which allows the strength and plasticity to be shaped.

Precious metal alloys

Precious metals include gold, silver, and platinum, and their alloys. They are distinguished by their very high resistance to corrosion in atmospheric conditions, in water, and in numerous chemical environments. At the same time, these metals have relatively low strength with very good plastic properties, which is why in applications exposed to abrasion and deformation (e.g., jewelry, dental elements), they are most often used in the form of alloys rather than as technically pure metals.

The mechanical data of pure metals show this specificity: gold has an Rm of about 130 MPa, a yield strength of about 50 MPa, and a hardness of about 20 HB with a reduction of about 95% and an elongation of about 55%. Silver has an Rm of about 160 MPa and a hardness of about 25 HB, with very high plasticity (Z about 95%, A10 about 60%). Platinum reaches an Rm of about 150 MPa and a hardness of about 50 HB, also with high plasticity (Z about 90%, A10 about 50%).

Gold is resistant to most acids and bases, which is why it is used, among other things, for chemical and galvanic gilding, in laboratory equipment, and in alloys used in electronics. Silver is particularly resistant to strong bases, but is poorly soluble in organic acids; thanks to its very good electrical conductivity, it is used in wires and electrical components, as well as for silver plating. Platinum is highly chemically resistant, although it dissolves in hot aqua regia; in the chemical industry, it is used both for its corrosion resistance and catalytic properties, as well as for the manufacture of laboratory equipment (meshes, crucibles, evaporators).

Gold and silver are mainly used in jewelry and dentistry as alloys because, in their pure state, they are too soft. Copper and silver are key additives in gold alloys. Melting gold with silver does not significantly increase its hardness, while the addition of copper increases hardness more noticeably, albeit at the cost of a certain decrease in corrosion resistance. For this reason, triple Au-Ag-Cu alloys are often used, which balance color, hardness, and chemical resistance. In Poland, the legally established gold fineness corresponds to 96%, 75%, and 58.3% Au content; historically, this corresponded to 23, 18, and 14 karats, respectively (pure gold is 24 karats). The third fineness alloys have the highest hardness and abrasion resistance, but they also have a distinctly reddish color due to the high copper content.

The main components of silver alloys are copper and zinc, and the legally established silver finenesses are 94%, 87.5%, and 80% Ag. The highest fineness is not usually used due to its insufficient hardness, while the second and third finenesses are used in artistic products, tableware, and accessories. From a technical point of view, it is also important to use silver alloys as hard solders, where they combine good mechanical properties and corrosion resistance with wettability. Platinum and its alloys are mainly used in industry: Pt-Ir alloys with a hardness of approximately 265 HB at 40% iridium (used in electrical engineering, electrochemistry, medicine, and jewelry) are of great importance, while platinum alloys with rhodium are used as catalysts and in the form of wires for the manufacture of thermocouples.

Other non-ferrous metal alloys – summary

The groups of alloys discussed show that in engineering, it is often not about the “maximum” strength of a material, but about a set of precisely selected properties. Bearing alloys are designed for friction, lubrication, and running-in properties, which is why the structure of hard inclusions in a soft matrix is crucial. Solder alloys are selected to control the wetting and solidification of the joint: soft solders ensure tightness, while hard solders allow for the construction of high-strength joints.

Low-melting alloys use their low melting point as a functional feature in safety components and precision technology. Zinc and its alloys combine the role of a structural material with the extremely important function of protecting steel against corrosion and the possibility of inexpensive production of die castings. Titanium and its alloys offer high corrosion resistance and excellent weight strength, especially in heat-treated α+β varieties. On the other hand, precious metals and their alloys are irreplaceable where chemical resistance, conductivity, or controlled hardness while maintaining high plasticity are decisive.

Below is a cross-sectional overview of non-ferrous metals and their alloys – properties and applications (material in English).