Sintered products

Powder metallurgy is a method of producing machine parts and tools by sintering metal powders in a solid state, and the resulting components are referred to as sintered products. Although the manufacture of certain items from powders (especially jewelry made from sintered fine gold grains) has been known for a long time, the development of modern sintering technology is relatively recent. The symbolic beginning of the modern approach to sintering is considered to be 1825, when platinum coins were minted in Russia using chemically obtained powder.

The rapid development of the electrical engineering industry accelerated the development of powder metallurgy. In 1909, light bulb filaments were made from tungsten, tantalum, and molybdenum powders, which was an important step in the use of metal powders in technology. After World War I, sintering began to be used in the production of tools, and during World War II, machine parts were increasingly obtained by sintering.

After the war, the technology developed dynamically, especially with the development of the automotive industry, which in some countries accounts for more than half of the sintered products. Apart from the automotive industry, sintered products are used, among others, in electrical engineering, the metal products industry, the machine tool industry, and the construction industry (e.g., fittings). In practical terms, it is difficult to identify an industry in which sintered products are not used.

Why sintering is sometimes better than melting

The most noticeable advantage of sintering is the ability to obtain components with a very precise shape, often so close to the final shape that costly and labor-intensive machining can be reduced. This results in lower material losses, which in this technology usually do not exceed about 7-10%.

Sintering also facilitates the production of high-purity materials without impurities, which sometimes cannot be removed in conventional metallurgical processes. Sintered materials do not undergo the segregation phenomena typical of alloy crystallization and thus do not exhibit the characteristic defects of the solidification process. Another important advantage is the possibility of combining components that could not be combined by melting, for example, due to large differences in solidification temperatures or a lack of mutual solubility. This also makes it easier to produce metal-ceramic materials (composites), which are practically unattainable in classical metallurgy.

The limitation is the economy of scale: sintering technology is mainly profitable in mass production due to the high cost of obtaining powders and expensive equipment and tools. It should also be remembered that the mechanical properties of sintered materials are usually lower than those of solid materials, as sintered materials retain a certain porosity. Depending on the application, porosity can be a disadvantage (when load-bearing capacity is important), but it can also be deliberately used as a functional feature (e.g., in self-lubricating bearings).

Metal powders as raw materials

The basic raw materials for the production of sintered products are pure metal powders (e.g., iron, copper, manganese) and alloy powders (e.g., bronzes, brasses, stainless steels). Powders can be produced by mechanical or physicochemical methods. Mechanical methods involve the fragmentation of the material by external forces without changing its chemical composition, while in physicochemical methods, the powder is produced as a result of physicochemical transformations and, as a rule, differs in composition from the starting material.

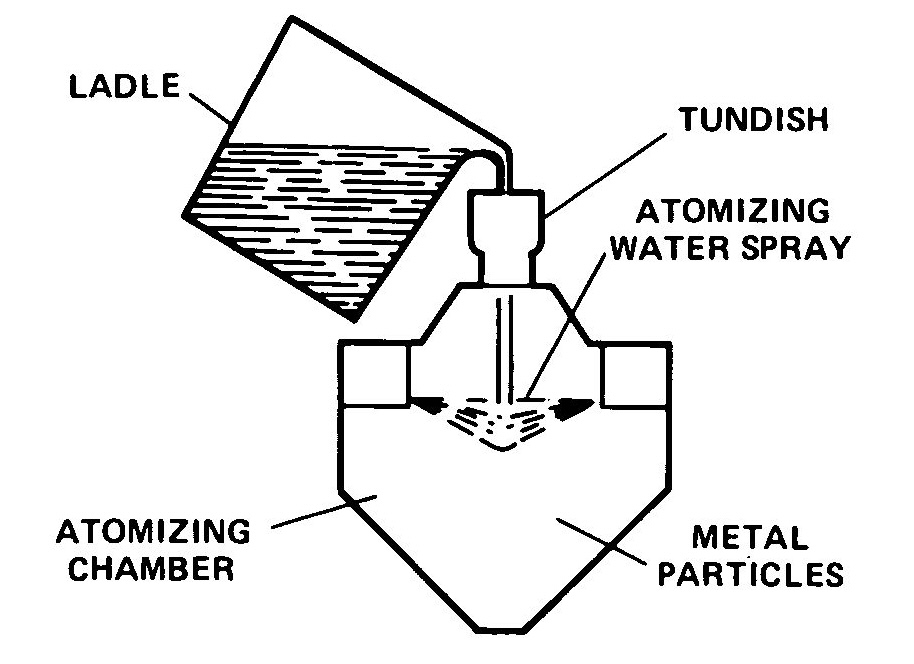

Mechanical methods include grinding metal in mills (e.g., ball, vortex-impact, hammer mills), grinding by machining (chips, filings), spray drying of liquid metal with water or pressurized gas, and granulation, which involves pouring liquid metal into water, where it solidifies into fine particles. The more commonly used physicochemical methods include oxide reduction (economical because it allows the use of ores or waste oxides from the smelting process), electrolysis from aqueous solutions or molten salts (important but costly due to energy consumption and lower efficiency), decomposition of carbonyls (producing very pure powders but expensive), condensation of metal vapors on a cold surface, and electroerosion methods, which historically remained underdeveloped for a long time.

Before the powder is formed, preparatory operations are carried out, which strongly influence the quality of the products. Annealing increases the plasticity of powders by reducing residual oxides and removing crushing; it is carried out in a reducing atmosphere or in a vacuum at a temperature of 0.4-0.6 of the powder’s melting point. Screening allows for separation into fractions of different particle sizes and enables control of the granulometric composition of the mixtures. Mixing is intended to produce as homogeneous a mixture as possible – its quality determines the subsequent repeatability of the density of the moldings and the parameters of the sintered products.

Forming of mouldings

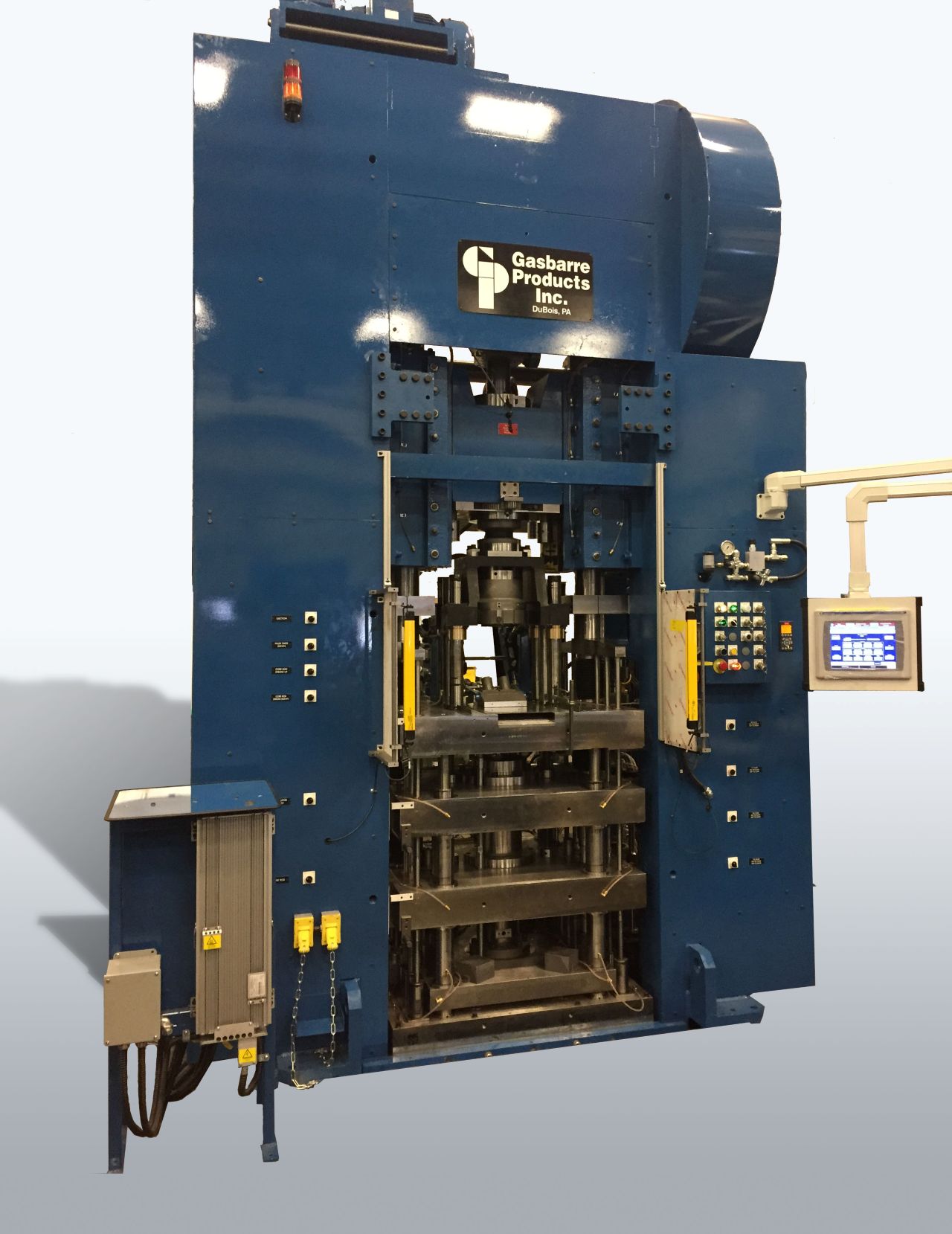

The prepared powder mixture is pressed to obtain semi-finished products, i.e., mouldings, with the desired shape and dimensions and the strength necessary for transport and further sintering. Most often, pressing is carried out in steel presses. The shape and dimensions of sintered products are largely limited by the pressing capabilities, which is why this operation determines whether a given part can be manufactured using the powder method at all.

A typical press consists of a die and upper and lower punches. The die shapes the side surfaces of the molding, the lower punch prevents the powder from spilling out and shapes the bottom surface, and the upper punch forms the top surface. The press may have additional elements, such as pins for shaping holes. There are double-sided pressing systems with a fixed die and solutions with a movable die, which facilitate the ejection of the molding.

The process of powder compaction during pressing takes place in stages. First, the particles fill the gaps and arrange themselves more and more compactly, striving for the densest possible arrangement. Further compaction occurs through the deformation of the particles and their mutual displacement. In practice, these mechanisms overlap: some particles deform even at lower pressures, and displacements can also occur at high pressures. Since pressing affects the initial density of the molded part and the porosity distribution, it directly influences the sintering process and the properties of the finished product.

Alternative forming methods when pressing is not sufficient

Classic pressing in a die imposes geometric limitations (especially in the direction of force) and can lead to an uneven density distribution in the molding. For this reason, special forming methods have been developed that allow elements with different proportions to be shaped, a more uniform density to be obtained, or details that are difficult to produce in a simple press to be made.

The materials cite hydrostatic pressing, die casting, powder rolling, extrusion, vibration forming, and dynamic forming with high deformation rates as examples of such methods. In practice, the choice of method is a compromise: on the one hand, the aim is to obtain a “non-machined” detail, while on the other hand, the costs of tooling, the required tolerances, the repeatability of density, and how the particular forming method affects subsequent sintering must be taken into account.

Sintering

Sintering involves heating the molded parts at high temperatures, during which the compressed powder is transformed into a sintered product with properties similar to those of a solid material. This is an essential stage of production and therefore attracts the most interest, but at the same time, it has long been emphasized that there is no single general theory covering the entire range of sintering phenomena. The process is carried out in a protective atmosphere or in a vacuum to protect the material from oxidation, and the sintering temperature is usually lower than the melting point of the most easily melted component.

The sintering process and the properties of sintered materials are primarily influenced by: powder granulation (greater dispersion accelerates sintering and promotes an increase in mechanical and electrical properties), pressing pressure (increasing it usually increases the strength of sintered materials), sintering temperature (the higher the temperature, the greater the density of the sintered material), and annealing time (at a constant temperature, the density increases rapidly at first and then more slowly, which affects the properties). The atmosphere of the process is also important: sintering in a reducing atmosphere results in sintered materials with a higher density than sintering in an inert atmosphere.

After sintering, finishing is often used, especially when tighter tolerances or better surface smoothness are required. Structural components may also undergo heat treatment and thermochemical treatment to increase wear and fatigue resistance or improve load-bearing capacity. This is why powder metallurgy is sometimes seen as a complete manufacturing technology: from powder, through forming and sintering, to final adjustment of dimensions and structure.

Introduction to powder metallurgy: from powders, through pressing, to sintering and typical applications (material in English).

Sintered materials and products

Among the more important sintered products are porous sintered materials, electrical engineering materials, materials with special magnetic properties, structural materials, sintered refractory metals, and sintered tools. Porous sintered materials are particularly characteristic and are used for slide bearings, filters, catalysts, washers, and components with a high friction coefficient.

Sintered bearings have very good sliding properties because lubricant circulates in the existing pores during operation. This facilitates the formation of an oil film between the journal and the bearing shell and produces a self-lubricating effect; in many cases, external lubrication may be unnecessary, which is important in hard-to-reach machine components. The porosity of sintered bearings is typically 10-35%, and an additional advantage is their quiet operation compared to rolling bearings. Their technology is simple, often does not require machining, and installation and operation are facilitated. The materials used for sintered bearings do not contain scarce components, which is why they are cheaper than cast solutions in many applications.

Historically, bronzes with compositions similar to casting bronzes were used for sintered bearings, and then additives were introduced to improve anti-friction properties, primarily graphite. It is indicated that the friction coefficient of such bearings could be 7–8 times lower than that of babbitt, and the wear of the journals was negligible. Porous iron and iron-graphite sintered materials were introduced as cheaper alternatives. The most commonly used bearing materials include porous iron, iron-graphite sintered materials with a graphite content of approximately 1-3% (the rest being iron), and graphite bronzes with a composition of approximately 86-88% Cu, 9-10% Sn, and 2-4% graphite. There are also sintered bearings on an aluminum base, for example, with a composition of approximately 10% Cu and 3% graphite (the rest is Al).

Filters made of sintered materials are widely used in the chemical industry. They are made from powders of corrosion-resistant materials such as bronzes, stainless steels, nickel, silver, and platinum, as well as refractory metals or their alloys. Thanks to their high porosity, filtration rates can be very high, which, combined with the simplicity of manufacture, favors the rapid development of this type of filter. Sintered materials (especially porous iron) are also used as sealing materials in the form of washers for pipe joints, couplings, flanges, and conduits.

Sintered materials are also a good material for components with a high coefficient of friction, such as brake pads and torque transmission components. Such applications require a high and stable coefficient of friction over a wide temperature range, high abrasion resistance with sufficient strength, good thermal conductivity, and resistance to corrosion and wear. Since these requirements are sometimes contradictory, sintering facilitates the production of a material “composite” of metallic and non-metallic phases: the metallic components promote thermal conductivity, while the non-metallic components (e.g., SiO2 or Al2O3) increase the friction coefficient and reduce wear.

Functional and structural sintered products

Sintered products are important in electrical engineering and communications because they have made it possible to replace expensive, scarce materials and produce plastics with unique properties. A classic example is electrical contacts, which must simultaneously provide high electrical and thermal conductivity, high melting point and corrosion resistance, high mechanical strength, and resistance to electroerosion. Combining different components in powder processes facilitates the achievement of such a set of characteristics.

Sintering is also used to obtain materials with special magnetic properties, especially magnetically hard materials, i.e., permanent magnets. Compared to casting, the production of magnets by sintering is more efficient, results in less material loss, and usually requires only minor finishing. Iron-nickel-aluminum alloys (AlNiCo, AlNiCo, Magnico) hardened by dispersion are indicated as materials for sintered magnets; it is emphasized that the properties of sintered magnets are better than those of cast magnets, and their brittleness is lower, although the presence of pores may slightly impair the magnetic parameters.

In the field of construction materials, sintering was initially used mainly for components that could not be manufactured by other means, but over time, the technology began to compete with casting and machining in the production of typical machine parts as well. Economically, mainly due to the cost of presses, the technology is usually only profitable for mass production – the materials indicate a threshold of over 50,000 pieces. The properties of sintered parts are slightly lower than those of cast parts, but in practice, parts with a porosity of 5-20% are often produced, considering such a decrease in properties to be acceptable in exchange for production benefits. Examples of sintered components include gears, piston rings, compressor blades, hubcaps, tees, and catch wheels; if necessary, these components can be further heat-treated or thermochemically treated.

Refractory metals, sintered tools, and reinforced composites

Sintering technology plays a special role in the production and processing of refractory metals such as tungsten, molybdenum, tantalum, niobium, and zirconium. These metals are important in nuclear and rocket technology, among other things, and due to their very high melting points, they are often obtained in powder form and only later pressed and sintered to obtain the required shape and density.

Tool sintered materials are also very important. In addition to sintered carbides (usually discussed separately as a group of tool materials), there are diamond-metal sintered materials intended for grinding. In such materials, it is crucial to combine a very hard abrasive phase with a matrix that allows for load transfer and abrasive grain stabilization, which is technologically feasible in the powder approach.

An important direction in the development of powder metallurgy is composite materials, i.e., fiber-reinforced metals. Fiber reinforcement allows for a particularly high yield strength even at high temperatures and increases resistance to brittle fracture. Examples include copper reinforced with tungsten or molybdenum fibers, developed aluminum alloys reinforced with steel wire, and iron reinforced with aluminum oxides or titanium and molybdenum fibers, which can increase its strength by up to 3-5 times. In this sense, powder metallurgy is a tool not only for shaping, but also for designing the architecture of the material.

Sintered products – summary

Sintering technology (powder metallurgy) allows the production of components from metal powders in a solid state, often in a shape very similar to the final one, which reduces machining and material losses. Its strength also lies in the possibility of achieving high purity and homogeneity, as well as combining components that are difficult or impossible to combine by melting, including the production of metal-ceramic materials.

Key factors for the quality of sintered materials are: the method of obtaining and preparing powders, pressing conditions (which determine the density of the pressed material), and sintering parameters (temperature, time, and atmosphere). The cost of powders and equipment remains a limitation, which is why the technology is most cost-effective in mass production, and the mechanical properties of sintered materials may be lower due to porosity.

The potential of powder metallurgy is best seen in applications where porosity is an advantage or provides functional benefits, such as self-lubricating bearings and filters, as well as in materials with complex, sometimes conflicting requirements (friction materials, electrical contacts, permanent magnets). The technology also plays an important role in the processing of refractory metals, tool materials, and fiber-reinforced composites, where it enables the design of the material’s “architecture.”