Polymer biomaterials

Table of contents

Synthetic polymers have become one of the most important groups of biomaterials today, alongside metals and ceramics. In medicine, they are used in disposable products, prostheses, dental materials, implants, dressings, extracorporeal devices, controlled drug delivery systems, and tissue engineering.

Their position is due to several key advantages. Polymers are relatively easy to process – they can be used to produce latex, films, fibres, tubes, porous scaffolds, and complex shapes using well-developed plastics processing technologies. They are characterised by a wide range of mechanical and physical properties, from hard and rigid structural materials to soft elastomers and hydrogels. In addition, they are often cheaper and lighter than metals and easier to modify chemically and superficially.

The requirements for polymeric biomaterials do not differ significantly from those for other implant materials. Above all, they are expected to be biocompatible (non-toxic, non-carcinogenic, non-pyrogenic and non-allergenic), sterilisable by typical methods (autoclave, ethylene oxide, radiation), as well as having appropriate mechanical and physical properties adapted to the function of the product and good processability (possibility of forming, extruding, injection moulding, fibre forming).

Basics of polymerisation and polymer structure

Polymers are formed by combining small molecules – monomers – into long chains. This process can take place through condensation polymerisation (stepwise) or addition polymerisation (chain, e.g., free radical).

In condensation polymerisation (step reaction), each stage of chain growth is accompanied by the release of a small molecule, most often water or alcohol. A classic example is the formation of polyamides (nylons) through the reaction of an amino group with a carboxyl group to form an amide bond and release water. This is how polyesters, polyamides, polyurethanes, polysiloxanes, as well as natural proteins and polysaccharides are formed, which are also produced by condensation with the release of water molecules.

In addition to polymerisation, typical for many medical plastics, the monomer usually contains a double bond, which is broken under the influence of an initiator – usually a free radical generated, for example, by peroxides (benzoyl peroxide) in the presence of heat or UV radiation. This is how a number of popular polymers are formed, such as polyethylene, polypropylene, polyvinyl chloride, polystyrene, and poly(methyl methacrylate).

The structure of a polymer macromolecule determines its properties. Chains can be linear, branched, or cross-linked. Linear polymers (e.g., classic polyesters or polyamides) can crystallise to a significant extent, forming a semi-crystalline system in which ordered areas coexist with amorphous ones. Cross-linking – as in the case of silicone elastomers or natural rubber after vulcanisation – limits the mobility of the chains, often prevents crystallisation, and leads to the formation of rigid three-dimensional networks.

The properties of polymers strongly depend on the degree of polymerisation, i.e., the number of repeating units in the chain, and on the location and distribution of substituents. The higher the molecular weight, the lower the mobility of the chains, which translates into greater strength and thermal stability, but also more difficult processing. The material is usually described by the average Mn (number-average mass) and Mw (weight-average mass), and the Mw/Mn ratio determines the polydispersity, which is important for the viscosity of the melt and the course of processing.

Another important parameter is tacticity, i.e., the order of substituents along the chain. In vinyl polymers, depending on the arrangement of side groups, isotactic, syndiotactic, and atactic configurations are distinguished. Iso- and syndiotactic arrangements favour crystallisation, even if the side groups are large, while the atactic configuration usually leads to an amorphous structure, as in the case of typical polystyrene.

Polymers are also characterised by transition temperatures: glass transition temperature (Tg) and melting temperature (Tm). Below Tg, an amorphous polymer behaves like glass – stiff and brittle, above – like a rubber body or viscous liquid. For semi-crystalline polymers, Tm describes the transition from the crystalline phase to the liquid state. The position of Tg and Tm depends, among other things, on the molecular weight, the presence of side groups, the degree of cross-linking, and crystallinity.

The most important polymers used as biomaterials

Although hundreds of polymers can be obtained relatively easily, in medical practice, a dozen or so types are commonly used, which have gained a good reputation in terms of biocompatibility, mechanical properties, and sterilisability.

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is an amorphous, rigid polymer whose chain contains large chloride groups. Its high glass transition temperature (approx. 75–105°C) makes it hard and brittle in its pure state. Therefore, plasticisers such as di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), as well as thermal stabilisers and processing lubricants, are added to PVC. The composition of the additives determines its flexibility, resistance to the extraction of components by blood and fluids, and stability during autoclave sterilisation. PVC is the basic material for blood and infusion fluid storage bags, infusion sets, dialyser components, tubes, catheters, and medical containers.

Polyethylene (PE) comes in many varieties: LDPE, HDPE, LLDPE, VLDPE, and UHMWPE with ultra-high molecular weight. By changing the polymerisation conditions and the type of catalyst, the degree of chain branching, crystallinity, and density can be controlled. LDPE is more branched and soft, while HDPE is linear and highly crystalline. Of particular importance is UHMWPE (Mw > 2·10⁶ g/mol), which combines high abrasion resistance, good mechanical properties, and biocompatibility, making it suitable for use in joint endoprosthetics as a hip socket or joint surface in knee prostheses.

Polypropylene (PP) has properties similar to polyethylene, but due to the presence of methyl groups, it has slightly higher stiffness and a higher melting point. Stereospecific polymerisation with Ziegler–Natta catalysts, which produces an isotactic polymer, plays an important role here. PP is distinguished by its excellent resistance to stress cracking and high ‘bending life’, which is why it is used, among other things, in disposable syringes, oxygenator membranes, surgical sutures, nonwovens, and some vascular prostheses.

Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) is an amorphous polymer with exceptional optical transparency, high refractive index, and good resistance to atmospheric ageing. It is one of the most biocompatible plastics and has therefore long been used as a material for eyeglasses and intraocular lenses, dental prostheses, blood pump components, reservoirs, dialyser membranes, and, in the form of a monomer-powder composite, as ‘bone cement’ for fixing joint prostheses. Thinly cross-linked derivatives, such as PHEMA or PAAm, form hydrogels used, among other things, in soft contact lenses.

Polystyrene (PS), obtained by free-radical polymerisation, is usually atactic and amorphous. In the GPPS version, it is transparent, rigid, and well-suited for injection moulding, while the rubber modification (HIPS) increases impact strength and crack resistance. In biomedicine, PS is primarily used as a material for cell culture vessels, rotary bottles, diagnostic and filtration kit components. ABS copolymer, containing acrylonitrile and butadiene, offers greater chemical resistance and better dimensional stability, used, for example, in medical device housings and dialyzer components.

In the polyester group, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is of key importance. It is a highly crystalline polymer with a high melting point, hydrophobic, and resistant to hydrolysis in weak acid environments. PET in the form of fibres is known as Dacron® and has been used for years in vascular prostheses, surgical sutures, surgical meshes, and heart valve components.

Polyamides (nylons), thanks to numerous hydrogen bonds between amide groups, form fibres with very good mechanical strength, ideal for forming threads. However, polyamides are hygroscopic – they absorb water, which acts as a plasticiser, reducing their elastic modulus and strength, and in biological conditions, they can undergo hydrolysis with the participation of proteolytic enzymes. For this reason, classic nylons lose their properties over time in an in vivo environment and today are more often used as suture materials with a limited residence time in the body than as permanent implants.

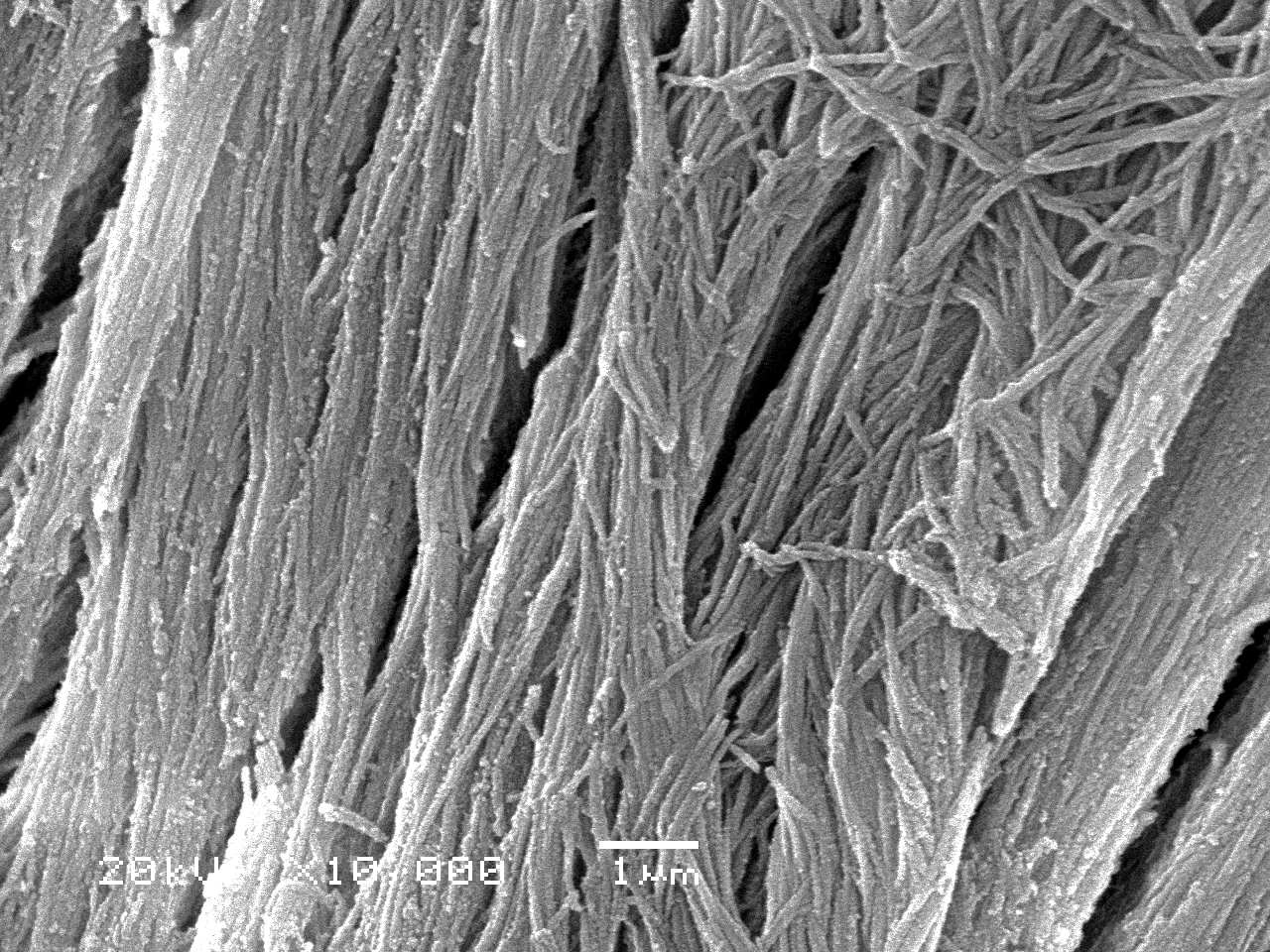

Fluoropolymers, primarily PTFE (Teflon®), are distinguished by a unique set of characteristics: very high crystallinity, low friction coefficient, low surface energy, and excellent chemical resistance. PTFE has relatively low tensile strength, but it can be processed by powder sintering and, after appropriate treatment, microporous, forming an ePTFE structure. This material is widely used as a vascular implant, catheter material, and components requiring excellent slipperiness and chemical inertness.

Among rubbers and elastomers, silicone rubber, composed of polysiloxane chains with methyl groups, occupies a special place. In its cross-linked form, it creates a soft, flexible material with very good biocompatibility, used, among other things, in breast implants, pacemaker leads, drains, and various soft prosthetic components.

Polyurethanes can be designed to achieve a wide range of modules – from soft elastomers to rigid foams. In medicine, they are used as coatings, tubes, components of mechanical devices, and as materials with increased resistance to abrasion in contact with blood and soft tissues. Thanks to the presence of soft and hard segments and the possibility of chemical modification, polyurethanes are one of the most versatile polymers for biomedical applications.

Another group is formed by high-strength polymers: polyacetals (POM, Delrin®), polysulfones (Udel®), and polycarbonates (Lexan®). They have rigid main chains, high thermal and chemical resistance, and good mechanical properties. For this reason, they are used in structural elements of medical devices, pump components, valves, housings, and some of them are being tested as potential implant materials.

Biodegradable polymers are becoming increasingly important, in particular PLA, PGA, PLGA copolymers, polydioxanone, polyalkanolactones, and carbonates. These are mostly polyesters from the α-hydroxy acid group, which undergo degradation by hydrolysis of ester bonds, leading to metabolites that are incorporated into the Krebs cycle (lactic acid, glycolic acid) and ultimately excreted as carbon dioxide and water. The degradation time of PLGA can be regulated by the composition of the copolymer and processing parameters, making it an excellent material for tissue engineering scaffolds and drug carriers in the form of microspheres. PGA works well as an absorbable suture and surgical mesh material, while PLA, due to its higher stiffness, can serve as a temporary support element in osteosynthesis.

Sterilisation of polymer biomaterials

Unlike metals and many ceramics, polymers have limited thermal and chemical resistance, which makes the choice of sterilisation method a crucial step in the design of a medical device.

Dry air sterilisation, carried out at temperatures of 160–190°C, is only suitable for polymers with very high thermal stability, such as PTFE or silicone. For most plastics, including polyethylene and PMMA, these temperatures exceed their softening and melting points, leading to deformation and degradation.

Autoclaving, or steam sterilisation under pressure at a temperature of approximately 125–130°C, is gentler in terms of heat, but has other requirements: the material must be resistant to hot water and steam. Polymers susceptible to hydrolysis, such as certain polyamides, PVC, or POM, may degrade or suffer stress cracking and are not suitable for repeated steam sterilisation.

Ethylene oxide gas is very often used, as it allows products to be sterilised at low temperatures. Although this method is relatively gentle on the material, it requires control of gas residues and sufficiently long aeration. However, some polymers may undergo gradual degradation or discolouration even under such conditions.

Radiation sterilisation using Co-60 sources is very effective, but ionising radiation can cause scission (chain breaking) or additional cross-linking, depending on the polymer structure. In polyethylene, a high dose leads to the formation of a hard, brittle material as a result of simultaneous chain cutting and bonding. Polypropylene, on the other hand, is susceptible to discolouration and brittleness after irradiation, with degradation of properties continuing over time after sterilisation. Therefore, for some applications, radiation-sensitive additives are avoided, and the composition is selected to minimise adverse effects.

Surface modifications

Since most biological interactions occur in the first few nanometres of the surface, a key tool in polymer engineering is the modification of the surface layer, often without significantly altering the bulk properties.

In devices that come into contact with blood – dialysers, vascular prostheses, artificial valves, extracorporeal circulation systems – the most important problem is thrombosis and platelet adhesion. The classic approach is to immobilise heparin and its analogues on the polymer surface. Heparin, an acidic glycosaminoglycan, inhibits the coagulation cascade, but its permanent binding to the surface is difficult, and slow release can be both desirable and problematic – too rapid ‘overgrowth’ of the surface with a layer of plasma proteins can reduce the availability of heparin to the blood.

Another strategy is to create surfaces that preferentially adsorb albumin, which is observed as a phenomenon associated with reduced platelet adhesion. Fibronectin coatings are used where the goal is to colonise the surface with endothelial cells, e.g., in attempts to create ‘biological’ vascular surfaces on synthetic grafts. Alginate coatings, due to their good biocompatibility and controllable degradation, have been tested as layers to improve the compatibility of vascular prostheses.

A large group consists of physicochemical modifications that change wettability, surface energy, charge, and topography. These include plasma treatments (oxygen, nitrogen, and fluorine plasma), vapour deposition of thin silicon and fluoropolymer coatings, hydrogel grafting, and ion implantation. The aim may be to increase resistance to abrasion and corrosion (e.g., diamond coatings, anodising) or to control protein adsorption and cell adhesion.

For example, polyethylene oxide (PEO) coatings significantly reduce protein adsorption and cell adhesion, making them promising candidates for ‘anti-adhesive’ surfaces for blood and cells. In turn, hydrophilic coatings, with a selected ratio of polar and dispersion interactions, can promote the adsorption of ‘passive’ proteins and reduce platelet activation.

Another interesting concept is the method of saline perfusion through the walls of porous tubes. The flow of saline solution through the micropores creates a thin layer of fluid separating the blood from the material, which can significantly reduce cell adhesion and clot formation. This method has been tested on porous tubes made of PE, ePTFE, polysulfone, and oxide ceramics, among others, with promising results both in vitro and in vivo.

Chemogradient surfaces

Classic studies of the influence of surface properties on the behaviour of cells or proteins require the preparation of many samples with different modifications, which is time-consuming and sensitive to biological variability. The answer to this problem is chemogradient surfaces – substrates whose properties change gradually along a single axis.

In the case of polymers, methods have been developed to create wettability gradients on polyethylene substrates using RF plasma or corona discharge. A polymer sheet is moved under an electrode so that the exposure time to the plasma gradually changes. The longer the exposure, the higher the content of oxygenated polar groups on the surface and the lower the water wetting angle, which corresponds to greater hydrophilicity. In this way, it is possible to obtain a surface on which the wetting angle decreases smoothly, e.g., from 95° to 45° over a length of several centimetres.

This type of substrate was used to study the adhesion and proliferation of various cell types, including Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. It was found that maximum adhesion, spreading, and growth occurred in the area of medium hydrophilicity, corresponding to a contact angle of approximately 50–55°. Both highly hydrophobic and highly hydrophilic surface fragments showed poorer cell colonisation.

A similar trend was observed for serum protein adsorption. The maximum amount of proteins, including fibronectin and vitronectin, was also adsorbed in the area of intermediate wettability, which correlates with optimal cell adhesion and growth. It follows that, from a surface engineering perspective, there is a wettability ‘window’ in which favourable adsorption of adhesive proteins and cell preservation are simultaneously promoted.

The chemogradient technique was then extended to functional group gradients – for example, –COOH, –CH₂OH, –CONH₂, or –CH₂NH₂ – obtained by a combination of corona treatment, vinyl monomer grafting, and substitution reactions. This made it possible to study the effect of surface charge, ionisable group density or polarity on cell behaviour, platelet adhesion and protein adsorption, still in a single experiment.

Chemically gradient surfaces prepared in this way are a powerful tool for rapidly mapping the relationship between surface properties and biological response, reducing the number of samples and decreasing the variation in results resulting from differences between cell lines or culture conditions. In the future, similar concepts may be applied in separation devices, biosensors, and surface ‘libraries’ for high-throughput screening of biomaterials.

Summary – Polymer biomaterials

Polymer biomaterials are an extremely diverse group of materials, including hard, structural thermoplastics (PE, PP, PET, POM, polysulfones, polycarbonates), soft elastomers (silicones, polyurethanes), hydrogels (PHEMA, PAAm), fluoropolymers (PTFE), and increasingly important biodegradable polymers (PLA, PGA, PLGA, polydioxanone). Thanks to the possibility of precisely shaping the chain structure, molecular weight, degree of cross-linking, and crystallinity, it is possible to design materials that are perfectly suited to the requirements of specific applications – from disposable infusion sets to long-term implants and controlled drug delivery systems.

Sterilisation and control of surface interactions with blood and tissues remain key challenges. This requires not only the selection of the appropriate polymer, but also the careful choice of sterilisation method and, most importantly, surface modification to achieve the desired biocompatibility profile. Modern techniques such as plasma treatment, hydrophilic and hydrophobic coatings, biomolecule immobilisation, hydrogel grafting, and chemically gradient surface design are paving the way for more precise control of biological responses.

As a result, polymers are no longer just ‘plastic in medicine,’ but highly engineered tools that can be tailored in terms of composition, structure, and surface to the requirements of a specific clinical task. Combining this flexibility with growing knowledge of cell-material interactions means that polymer biomaterials are likely to play an even greater role in the future of implantology, tissue engineering, and medical technologies.