Basics of heat treatment of steel and cast iron

Table of contents

Heat treatment is a set of activities aimed at changing the structure of an alloy in a solid state, thereby obtaining desired mechanical, physical, or chemical properties. In practice, this means that we do not ‘improve’ the metal by simply heating it, but by ensuring that a properly planned temperature curve over time triggers structural changes: the formation of new phases, the decomposition of unstable phases, changes in grain size, as well as the separation of carbides or the removal of internal stresses. Heat treatment includes both simple processes involving heating and cooling, as well as more complex processes combined with chemical interaction with the environment, plastic deformation, or a magnetic field.

The importance of heat treatment is particularly evident in the case of steel and cast iron. Iron as a base material is common, cheap, and easy to process, but it is the ability to control its structure that makes the range of steel applications so wide. The existence of allotropic varieties of iron plays a key role here: different varieties of crystal structure are stable at different temperatures, which makes it possible to produce and ‘freeze’ different microstructures depending on how quickly we cool the material and whether we perform additional annealing. This is why steel can be used as a material for springs, cutting tools, machine components, and load-bearing structures – and the differences in behaviour result not so much from the ‘composition itself’ as from the microstructure obtained during heat treatment.

Modern industry is placing greater demands on materials, which is driving the development of heat treatment methods and greater quality control. Even minor errors – too high a tempering temperature, too short a heating time, inadequate cooling – can cause undesirable structures (e.g., too coarse grain) and, as a result, impair the functional properties of the product. Therefore, heat treatment is not an ‘addition’ to the manufacturing technology, but one of its critical stages.

The relationship between phase equilibrium systems and heat treatment

Phase equilibrium systems describe which phases are stable under given temperature and composition conditions, but they do so on the assumption of very slow transformations, i.e., those in which time does not limit diffusion and the system has a chance to reach equilibrium. For this reason, the equilibrium diagram itself does not take into account the effect of heating and cooling rates. Nevertheless, equilibrium systems form the basis for planning heat treatment because they indicate what transformations are possible and in what temperature ranges they can be expected.

This distinction is very practical. If an alloy does not exhibit transformations in the solid state (there are no areas on the diagram where a different phase or mixture of phases appears in the solid state), then such an alloy is essentially not heat treatable in the classical sense, because it has no ‘mechanism’ for changing its structure. The situation is different in systems where the solubility of a component in the solid state depends on temperature. In this case, it is possible to obtain a supersaturated solution by rapid cooling from a temperature at which solubility is high, and then forcing precipitation during reheating. This scheme leads to a deliberate change in structure and properties.

Yet another situation occurs in alloys undergoing allotropic transformations in the solid state: at high temperatures, one phase is stable (e.g., a solid solution with a different lattice), and after exceeding critical temperatures, the system tends to form a mixture of other phases. Then, the very speed at which we pass through the transformation range is of fundamental importance, because with slow cooling, diffusion keeps pace and equilibrium structures are formed, while with rapid cooling, non-equilibrium structures such as martensite are possible.

For steel, the key part of the equilibrium system is iron–cementite (Fe–Fe₃C) up to about 2.11% carbon, which is the range relevant to steel. This is what gives meaning to austenitisation (heating to the austenite range) and the fact that during cooling, austenite can transform into different structures depending on the cooling rate. The equilibrium system tells us ‘what is possible’ and ‘where the critical temperatures lie’, while the kinetics of the transformations (time and cooling) determine ‘what we actually get’.

Heating, soaking, and cooling

Each heat treatment process can be treated as a scenario of temperature changes over time, in which three main stages can be distinguished: heating, soaking, and cooling. Heating involves raising the temperature to the value specified for a given process. Gradual heating is often used: first, heating to a lower temperature, and only then further heating to the correct temperature. This division is not artificial – it is technologically significant because it limits temperature gradients across the cross-section of the element and reduces the risk of cracks or excessive stresses.

Aging is maintaining the temperature at the target level for the time needed to equalise the temperature throughout the cross-section and for the intended changes to take place. In practice, annealing has a dual purpose: on the one hand, the element must ‘reach’ the temperature thermally (otherwise the surface and core will be in different states), and on the other hand, many transformations – especially diffusion – require time to homogenise the phase composition or dissolve certain components (e.g. carbides).

Cooling is the lowering of the temperature to ambient temperature or to a specific intermediate value. Slow cooling, e.g., in a furnace or in still air, is called annealing, while rapid cooling in water or oil is called quenching. Gradual cooling is also common, where undercooling to a temperature higher than the final temperature and overcooling to the final temperature occur. This method of control is sometimes necessary when we want to pass through certain temperature ranges more slowly (to allow diffusion) or more quickly (to avoid pearlitic diffusion transformations and obtain martensite).

Since the essence of heat treatment is the relationship between temperature and time, it is described by the curve t = f(τ). In practice, we talk about the average heating and cooling rates, but the actual instantaneous rate is equally important, as it determines how quickly we pass through critical temperature ranges. For this reason, two processes with ‘similar total times’ can produce different results if they differ in the cooling process in critical ranges.

Classification of heat treatment

The division of heat treatment is not purely ‘encyclopaedic’ – it results from the tools we use to change properties. In conventional heat treatment, the desired characteristics are obtained by changing the structure without changing the chemical composition. This includes classic processes such as annealing, hardening, and tempering, but also supersaturation and ageing, where the mechanism involves obtaining a supersaturated solution and subsequent precipitation.

In chemical heat treatment, in addition to temperature, a chemical environment is used to saturate the surface with elements such as carbon or nitrogen. The result is a change in the composition of the surface layer, and thus a change in structure and properties, especially wear or fatigue resistance. This is an important distinction: in ordinary heat treatment, we ‘work’ on what is already in the alloy, while in thermochemical treatment, we additionally supply a component.

Thermoplastic treatment, on the other hand, combines temperature with plastic deformation, which allows the structure to be influenced in a more complex way, e.g., by grain refinement and mechanical strengthening. Thermomagnetic treatment uses a magnetic field to obtain specific physical properties. In the context of steel and the basics of heat treatment, however, the focus remains on conventional heat treatment, as it is directly related to the transformation of austenite and its decomposition products.

Transformations during heating

In the heat treatment of steel, the heating stage is not limited to ‘heating the element’. Its purpose is to obtain an austenitic structure, because austenite is the starting point for many subsequent structures after cooling. After reaching the critical temperature A₁ (approximately 727°C), a fundamental transformation takes place: pearlite transforms into austenite. The subsequent heating process depends on whether the steel is hypoeutectoid, eutectoid, or hypereutectoid. In hypoeutectoid steels, after the formation of austenite from pearlite, as heating continues, the remaining ferrite also transforms into austenite, and the process ends at the Ac₃ temperature. In hypereutectoid steels, after the transformation of pearlite into austenite, secondary cementite dissolves in austenite, and the process continues up to the Ac_cm temperature. In both cases, the aim is to obtain austenite that is as homogeneous as possible.

The transformation of pearlite into austenite itself has a distinct ‘internal’ process structure. It begins with the formation of austenite nuclei at the boundaries of ferrite and cementite, and then the nuclei grow, filling the pearlite grains. At the same time, cementite dissolves in austenite. Importantly, the allotropic transformation of iron occurs faster than the complete dissolution of carbides, so at some point, we may have austenite that still contains carbide residues and is also chemically heterogeneous. Only with time does homogenisation occur through carbon diffusion. As a result, the material distinguishes between stages: the formation of heterogeneous austenite, the dissolution of carbide residues, and only then complete homogenisation.

The heating rate is also of great importance. Under very slow heating conditions, the transformation begins at around 727°C, but with faster heating, it shifts to higher temperatures. This means that in practical terms, it is not enough to know the ‘textbook’ critical temperatures – it must be taken into account that the actual range of transformation depends on kinetics and the initial microstructure. The rate of austenitisation is also influenced by the dispersion of pearlite and the form of cementite, as well as the chemical composition of the steel, including alloying additives.

Grain size in steel

In steel, a distinction is made between primary grain (after solidification) and secondary grain, i.e., the actual grain – the last austenite grain formed as a result of heat and plastic treatment. This actual grain is crucial for properties, especially impact strength. A material with a coarse-grained structure after cooling tends to be brittle and have low impact strength, which is why the technology aims to obtain fine austenite grain and then ‘transfer’ this fine grain size to the structure after cooling.

It is worth noting the mechanism of grain changes during heating. The transformation of pearlite into austenite itself promotes fragmentation, but further annealing at high temperatures causes austenite grain growth, as the metal tends to reduce the energy of the grain boundaries. The higher the heating temperature and the longer the annealing time, the greater the grain growth. This explains why ‘too hot and too long’ can be destructive: even if we obtain full austenite, it can become coarse-grained, which impairs fracture resistance.

In this context, the concept of overheating arises, i.e., the tendency of austenite grains to grow under the influence of temperature and time. In practice, fine-grained and coarse-grained steels are referred to not in terms of ‘what grain they happen to have’, but in terms of ‘how easily that grain grows during austenitisation’. Nominal fine-grained steel can have a coarse grain if it has been overheated; conversely, steel with a greater tendency to grow can produce a fine grain at the right temperature. This is important because it teaches caution: the name of the steel does not exempt you from controlling temperature and time.

The material also indicates the role of additives such as aluminium, which can inhibit grain growth by forming oxides or nitrides. From a technological point of view, this translates into greater process tolerance: steels less prone to overheating have a wider safe hardening temperature range and a lower risk of impact strength deterioration due to accidental overheating.

Austenite transformation kinetics

After austenitisation, the key question is: what happens to austenite during cooling? Below 727°C, austenite becomes an unstable phase and tends to transform into structures with lower free energy, such as pearlite. However, the course of the transformation depends on two opposing factors. On the one hand, greater supercooling increases the thermodynamic ‘drive’ of the transformation, while on the other hand, lowering the temperature slows down diffusion, without which pearlitic transformations cannot proceed efficiently. As a result, the rate of transformation increases to a certain maximum (approximately 550°C) and then decreases with a further drop in temperature, down to a range where diffusion is practically ‘frozen’ and non-diffusive transformations occur.

To describe this quantitatively and clearly, austenite transformation diagrams are used. Under isothermal conditions, when austenite rapidly cools to a constant temperature and remains there, a characteristic period is observed in which nothing happens – this is the incubation period (austenite stability). Only after this period does the transformation begin and proceed to completion. If we perform such experiments for different temperatures and plot the start and end times of the transformation, we obtain a CTPi (time-temperature-isothermal transformation) diagram with C-shaped curves. The distance between the start and end curves indicates the rate of transformation in a given temperature range.

Isothermal graphs allow us to distinguish three main ranges: at temperatures close to A₁, a pearlitic transformation with high austenite stability occurs; in the medium temperature range (approximately 550–200°C), bainite appears; and below the Ms line, the diffusion curves disappear because a martensitic transformation with a different mechanism begins. This picture is fundamental because it shows that ‘austenite’ is not a single transformation path – it is a starting point from which different structures can be reached depending on the cooling path.

Pearlitic transformation

Pearlitic transformation is a diffusion process. It usually begins with the appearance of cementite nuclei at the boundaries of austenite grains, after which, thanks to carbon diffusion, cementite grows into plates, and carbon-depleted austenite transforms into ferrite. Repetition of this mechanism leads to the formation of alternating bands of ferrite and cementite, i.e., a pearlite structure. Several pearlitic colonies usually form in a single austenite grain, and their geometry and fineness depend on the transformation temperature.

A key consequence of the kinetics is that as the undercooling increases, the number of nuclei and the rate of crystallisation of the transformation products increase, but at the same time, the possibility of long-range diffusion decreases. As a result, pearlite with an increasingly smaller interplate spacing is formed – from coarse-grained pearlite at temperatures close to A₁ to very fine pearlite at lower transformation temperatures. This change in microstructure has a direct impact on properties: the finer the pearlite, the higher the hardness and strength, but usually at the expense of plasticity. The material indicates that pearlite formed at around 700°C can have a hardness of ~220 HB, while at around 500°C, very fine pearlite with significantly higher hardness is formed.

For hypoeutectoid and hypereutectoid steels, it is important that, under certain conditions, ferrite (hypoeutectoid) or secondary cementite (hypereutectoid) may be secreted before the pearlitic transformation. However, as the undercooling increases, this stage may disappear, and the transformation may proceed more ‘directly’, which is associated with the observed widening of the ranges in which pearlitic structures are formed without a distinct ferrite or cementite network.

Martensitic transformation

Below the Ms temperature, the transformation of austenite occurs in a completely different way, as carbon diffusion is practically inhibited. In this case, no products requiring the separation of carbon into ferrite and cementite are formed, but rather a non-diffusive restructuring of the iron crystal lattice occurs. Austenite transforms into martensite without changing the average carbon content in the solid solution, which means that martensite is a supersaturated solution of carbon in α iron. This supersaturation distorts the lattice into a tetragonal form, and it is this distortion that is responsible for the very high hardness of martensite, but also for its brittleness.

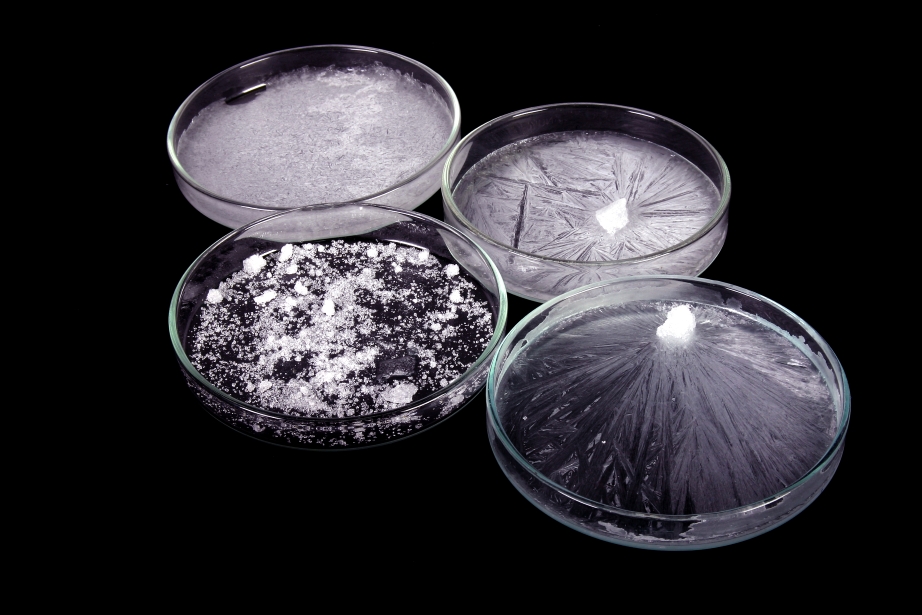

An important, often overlooked consequence of martensitic transformation is a volume change. Of the products of austenite transformation, martensite has the highest specific volume. In practice, this means that hardening involves the risk of significant stresses, deformations, and even cracks, especially in components with complex geometries. The material refers to dilatometric observations, which show characteristic volume changes associated with transformations during heating and cooling.

Martensite is formed without an incubation period: once Ms is exceeded, the transformation begins immediately, and the increase in the amount of martensite occurs through the formation of new plates (needles) rather than through the growth of existing ones. It is also very important that the transformation ends at the Mf temperature, but despite this, some austenite may remain untransformed as remanent austenite. Its amount depends heavily on the carbon content – at higher carbon contents, the proportion of remanence austenite increases after hardening, which affects hardness and dimensional stability.

Bainitic transformation

In the intermediate temperature range (for carbon steels, approximately between 550°C and 200°C), a bainitic transformation takes place, which combines the characteristics of diffusive and non-diffusive transformations. At these temperatures, carbon diffusion in austenite is already very low, but not zero. Carbon-saturated ferrite plates are formed from austenite, and then, because carbon diffusion in ferrite is greater than in austenite, carbides (cementite) are released from the saturated ferrite. As a result, bainite is a mixture of ferrite and carbides, with their fragmentation increasing as the transformation temperature decreases.

A distinction is made between upper bainite (formed at higher temperatures in this range) and lower bainite (at lower temperatures), which differ in morphology and hardness. The material provides approximate values indicating that upper bainite can have a hardness of about 45 HRC and lower bainite about 55 HRC, which shows its ‘position’ between typical pearlite and martensite. In addition, it is indicated that in carbon steels, the pearlitic and bainitic ranges may partially overlap, leading to mixed structures.

Austenite transformation during continuous cooling

Although isothermal diagrams are very informative, most actual technological processes take place under continuous cooling rather than isothermal cooling. Therefore, CTPc (time-temperature-transformation for continuous cooling) diagrams are constructed, which take into account the fact that the temperature decreases over time and the material ‘crosses’ different transformation ranges. Such diagrams are particularly useful because they allow direct comparison of cooling curves with transformation lines and predict what structure will be formed in a specific process.

With very slow cooling, the transformations are similar to equilibrium transformations: in hypoeutectoid steels, ferrite is first secreted (from Ar₃), and then a pearlitic transformation occurs in Ar₁. As the cooling rate increases, the transformation temperatures decrease, and some stages may disappear, e.g., the earlier precipitation of ferrite before pearlite may gradually disappear, leading to a more homogeneous pearlitic structure. A further increase in the cooling rate shifts the system towards bainite, and at even higher rates, bainite-martensite structures appear, until finally, at a sufficiently high rate, it is possible to obtain almost exclusively martensite.

This is where the concept of critical cooling rate comes in – the minimum rate at which a homogeneous martensitic structure is obtained (of course, with some residual austenite). This concept is practical: it tells us whether a given component can be hardened ‘through and through’ in a given cooling medium and with given dimensions. CTPc diagrams, especially when they include cooling curves and corresponding hardness values, allow us to directly read what proportion of phases (e.g., ferrite, bainite, martensite) we will obtain for a specific cooling process.

Tempering

Martensite is an unstable phase, and hardened steel, although very hard, can be too brittle and full of internal stresses. Tempering is therefore a process that uses controlled heating of hardened steel to higher temperatures to initiate changes in martensite. The key point is that tempering is not a single phenomenon, but a sequence of temperature-dependent stages. The material distinguishes four main stages, which differ in terms of the carbides that are secreted, how the carbon content in martensite changes, and when the residual austenite transformations occur.

At low tempering temperatures (around 80–200°C), the first stage occurs, involving the precipitation of ε carbide. This can even temporarily increase the hardness of high-carbon steels, which is an important, counterintuitive observation: tempering does not always mean softening from the very first minute. Then, in the range of approx. 200–300°C, further precipitation of ε carbide and diffusion transformation of residual austenite into a bainitic structure occur. In the range of approx. 300–400°C, ε carbide transforms into cementite, and a state closer to equilibrium is achieved; tempered martensite is then formed. At higher temperatures (approx. 400–650°C), cementite coagulates, stresses are removed, and a structure called sorbite is formed, offering a more favourable compromise of properties.

From a technological point of view, the purpose of tempering is that as hardness decreases, plasticity and impact strength increase. The material emphasises that optimum mechanical properties are often achieved when tempering in the range of approximately 600–650°C, and beyond that, the increase in plasticity is no longer as pronounced. In addition, it is important to distinguish between structures with similar hardness but different cementite morphology: fine pearlite and the structure after martensite tempering may look similar and have similar hardness, but they differ in the shape of carbides and thus in certain properties, e.g., yield strength or necking.

The effect of heat treatment on the properties of steel

Hardening leads to the formation of martensite, and thus to high hardness, the increase of which is related to the increase in carbon content. The material indicates that up to a certain level of carbon content (approximately 0.7%), the increase in martensite hardness is particularly strong, and then the increases are smaller. At the same time, in hypereutectoid steels hardened from very high temperatures, a higher proportion of residual austenite may appear, which can change the observed hardness and behaviour of the steel.

Tempering changes this picture: low temperatures can produce minor strengthening effects in high-carbon steels, but in general, an increase in tempering temperature leads to a decrease in hardness and strength and an increase in plasticity and impact strength. Importantly, this is not a matter of the ‘magical effect of temperature’, but of very specific transformations: the precipitation of carbides from martensite, a decrease in tetragonal structure, the transformation of carbides into cementite, and their coagulation. It is the microstructure – more specifically, the form and distribution of carbides and the state of the solid solution – that is responsible for the observed properties.

A comparison of pearlitic structures and structures obtained by tempering martensite is particularly instructive. Although they may have similar hardness and a similar ‘general’ appearance, cementite in pearlite has a striped form, while in structures after martensite tempering, it more often has a more granular (globular) form. The material points out that at the same hardness, tensile strength and elongation may be similar, but the yield strength and reduction of area are sometimes more favourable for structures after tempering. This explains why heat treatment (hardening + tempering) is so popular: it provides a set of properties that are difficult to obtain by cooling to pearlite alone.

Basics of heat treatment of steel and cast iron – summary

The theoretical basis of heat treatment of steel boils down to understanding that the process is controlled by the transformation of austenite. The Fe–Fe₃C equilibrium system indicates the critical phase and temperature areas, and the kinetics tell us which transformations will occur at a given cooling rate. The CTPi and CTPc diagrams show where austenite is stable, where it breaks down into pearlite or bainite, and where it transforms into martensite without diffusion. Tempering, on the other hand, organises the hardened state: it removes stresses and changes the form of carbides, leading to the functional properties needed in practice.

In this sense, heat treatment is not a set of ‘recipes’, but a logical consequence of the relationship: temperature + time + cooling rate → microstructure → properties. The better we understand this relationship, the more confidently we can select technological parameters, minimise the risk of defects, and consciously shape the material to meet design requirements.