Magnesium and its alloys

Table of contents

Magnesium is a silvery-grey metal and, most importantly from an engineering point of view, has the lowest specific weight of any metal commonly used in technology, at around 17.1 kN/m³. For this reason, magnesium-based alloys are referred to as ultra-light alloys, as they allow for the construction of structures with very low weight. At the same time, magnesium has no allotropic forms, so it does not ‘offer’ as many structural transformations as iron; its properties are mainly determined by the alloy composition, the state of casting/processing, and any heat treatment.

However, pure magnesium has clear mechanical limitations. In its cast state, its properties are relatively low: Rm approx. 80–120 MPa, Re approx. 20 MPa, A5 approx. 4–6% and hardness approx. 30 HB. This means that as a structural material ‘on its own’ it is too weak and not ductile enough to compete with typical aluminium alloys or steels. In addition, at room temperature, magnesium is brittle and can only be plastically processed at temperatures above approximately 220°C, which affects both the choice of manufacturing technology and costs. In practice, this is why magnesium in the form of alloys, rather than as a pure metal, is of primary importance.

Chemical activity, corrosion, and safety

Magnesium is a chemically very active metal, which has direct operational implications. It dissolves easily in many inorganic acids, but behaves more neutrally in alkalis. When exposed to air, it is covered with a thin layer of oxide, which gives it a poorer appearance, but at the same time can act as a protective layer, provided that there are no chlorine salts in the atmosphere. In the presence of chlorides (e.g., near the sea), soluble magnesium chlorides are formed, which do not form a tight barrier and constantly expose fresh metal, allowing corrosion to easily penetrate deep into the metal. This is one of the reasons why the choice of magnesium alloy and possible surface protection is critical in ‘salty’ environments.

Another important issue is the reaction of magnesium with water at elevated temperatures. Water heated to approximately 100°C in the presence of magnesium can decompose, leading to the oxidation of magnesium, and at higher temperatures, the process can be violent, as the hydrogen released can burn explosively. For this reason, the material clearly states that extinguishing burning magnesium with water is unacceptable.

The flammability of magnesium strongly depends on its form. Large elements, finished products, scrap, or sheets are practically non-flammable under normal conditions – to ignite them, they must first be partially melted. However, magnesium in the form of sawdust, shavings, strips, or powder can ignite easily because small particles heat up and melt quickly; once ignited, the shavings can burn until the material is completely consumed, and moisture can accelerate the explosive nature of the combustion. This aspect is not a ‘curiosity’ but a practical safety requirement in machining and storage of production waste.

Applications of pure magnesium and the meaning of alloying

The application of pure magnesium is limited, but not zero. Due to its high combustion heat and bright flame, it is sometimes used in the production of artificial light, in ignition and explosive materials, in thermotechnical reduction, and as a deoxidiser in the metallurgy of many metals. At the same time, magnesium is of major industrial importance as a matrix for alloys, because only alloying additives allow for the achievement of mechanical properties and corrosion resistance that are useful in construction.

The material also indicates the grades of metallurgical magnesium according to the standard (e.g., Mg 99.95 and Mg 99.9) and their typical uses, which shows that the purity of magnesium is selected depending on whether it is to be used in chemical applications and special alloys or in the production of standard magnesium alloys. In practice, it is alloying that ‘transfers’ magnesium from niche applications to classic structural applications where weight is a key parameter.

The most important magnesium alloy systems

Three additives are of fundamental importance in magnesium alloys: aluminium, zinc, and manganese. Aluminium significantly improves the mechanical properties of magnesium alloys; the material shows that the highest strength is achieved by an alloy with a content of approximately 5% Al, and the highest elongation by an alloy with a content of approximately 6% Al. Zinc acts similarly to aluminium, and the best properties are exhibited by an alloy with a content of approximately 5% Zn. These values are important because they suggest that there is a certain ‘optimal’ level of additive, above which proportional benefits are no longer achieved.

Manganese plays a special role in magnesium alloys because it not only improves mechanical properties but also increases corrosion resistance. In practice, this means that manganese is sometimes a ‘strategic’ additive for alloys that are to be used in more difficult environments or in conditions where surface protection is limited. It is the Mg–Al–Zn combination (often with Mn) that forms the most important family of magnesium alloys, known as electrons, widely used where weight minimisation is important.

An important feature of these additives is that their solubility in magnesium decreases with decreasing temperature, which opens the way for precipitation (dispersion) hardening. This property is the basis for the heat treatment of magnesium alloys, although, as the material emphasises, the effects of heat treatment are usually less spectacular than in aluminium alloys, so the choice of composition and manufacturing technology is often more important than heat treatment ‘for the sake of it’.

Heat treatment of magnesium alloys

Since the solubility of alloying additives in magnesium decreases with decreasing temperature, the classic dispersion hardening scheme can be used: first, a supersaturated state is created, and then controlled precipitation is induced during ageing. The material describes this process directly: the alloy is annealed at a temperature of approximately 345–420°C for 16–20 hours, then cooled in air to achieve supersaturation with alloying elements, followed by ageing at 150–200°C for approximately 12 hours, which increases the strength properties with a slight decrease in elongation.

However, it is worth grasping the practical meaning of this description. Firstly, the long annealing time suggests that it is crucial to equalise the composition and prepare the matrix for subsequent precipitation, rather than just ‘heating it’. Secondly, ageing is controlled: it is not about maximising hardness, but about achieving a stable compromise of properties. Thirdly, the material clearly indicates that although this treatment works, it does not provide as much improvement in properties as in aluminium alloys, which is why it is less important in magnesium alloys and is often used selectively, mainly where it is important to ‘squeeze’ out an additional margin of strength while maintaining low weight.

A good example of the effect of heat treatment is the MgAl10ZnMn alloy, for which the material specifies properties in different states. In the raw state, it achieves approximately Rm 150 MPa, A5 approximately 1%, and HB approximately 50. After homogenisation, approximately Rm 210 MPa, A5 approximately 3%, and HB approximately 60. After dispersion hardening, approximately Rm 210 MPa, A5 of approximately 1%, and HB of approximately 65. This set of figures shows a typical feature of some magnesium alloys: it is possible to significantly increase the strength compared to the raw state, but this is often at the expense of plasticity, and the ‘gain’ in hardness is not always so great as to justify heat treatment in every application.

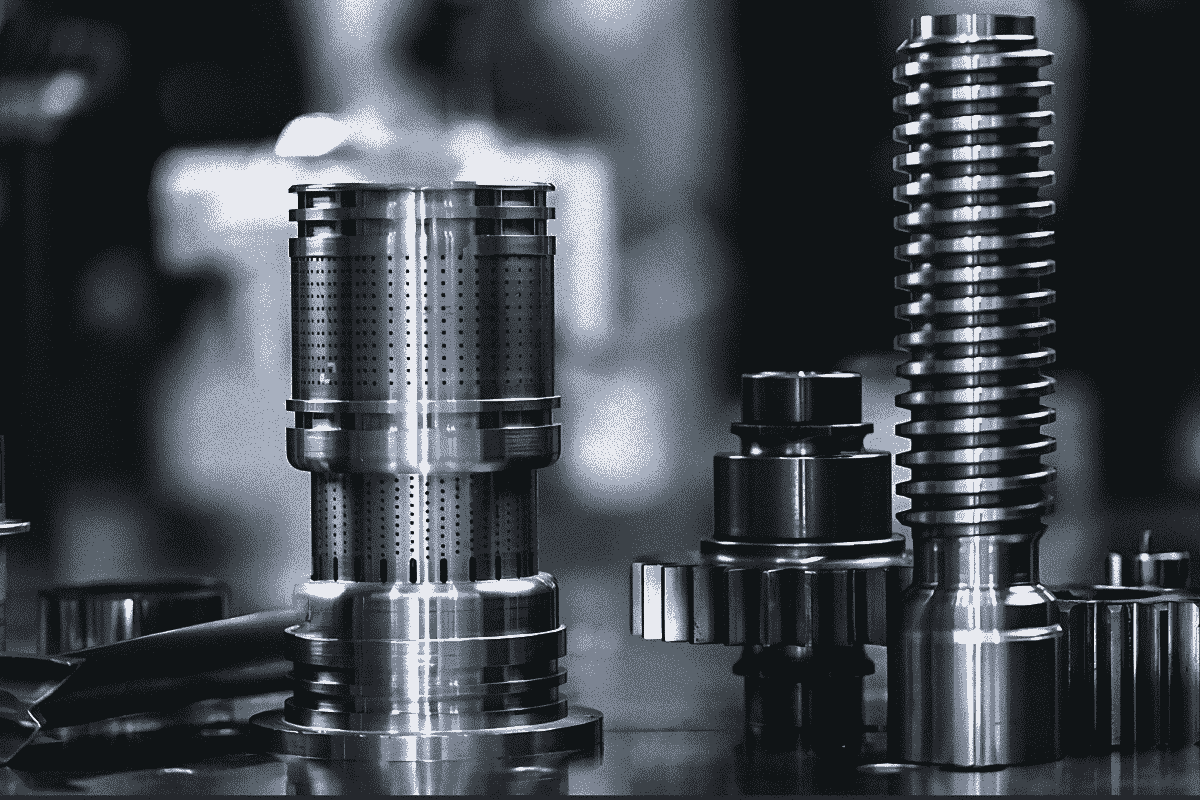

Casting alloys and wrought alloys

Magnesium alloys are divided – similarly to aluminium alloys – according to the manufacturing technology into casting alloys and wrought alloys. Both groups can be used either without heat treatment or after heat treatment, but their ‘natural’ advantages are different: casting alloys facilitate the formation of complex geometries, while wrought alloys are designed to achieve a better combination of strength and plasticity after hot deformation.

The designation of magnesium alloys is based on the general principles of marking non-ferrous metal alloys. The material gives an example that an alloy marked MgAl3ZnMn contains, in addition to magnesium, approximately 3% aluminium, approximately 1% zinc, and approximately 0.3% manganese. This notation is practical: it allows you to quickly recognise whether you are dealing with the Mg–Al–Zn–Mn family, i.e., ‘electrons’, and what level of properties and susceptibility to heat treatment you can expect.

Magnesium casting alloys typically contain aluminium, zinc, and manganese, and the material indicates that with a content of above 6% Al, they can be dispersion hardened. On the other hand, wrought alloys are usually multi-component alloys with Al, Zn, and Mn, with a lower aluminium content than casting alloys, up to a maximum of approximately 9%. They are processed at elevated temperatures: pressing in the range of approximately 250–420°C or rolling in the range of approximately 280–350°C, and, importantly, not only the material but also the tools are heated to reduce the risk of cracking during deformation. The material also points out that these alloys have good machinability, which is important in the production of thin-walled and precision components.

For plastically workable alloys, typical property ranges are given: Rm approximately 200–320 MPa, A5 approximately 12–23%, and HB approximately 40–55, with these properties remaining almost unchanged up to approximately 100°C. This set of figures clearly illustrates the technological significance of plastic working: compared to pure magnesium and many casting alloys, it is possible to achieve both higher strength and significantly better plasticity, which broadens the range of structural applications.

Applications of magnesium alloys

Magnesium alloys, both cast and wrought, have a specific weight of approximately 17.65 kN/m³, which in practice means that they are extremely advantageous materials where the weight of the structure is critical. The material has typical areas of application: the construction of cars, aeroplanes, and rolling stock, i.e, industries where weight reduction translates into energy savings, range, or load capacity. At the same time, there is also a more ‘utilitarian’ application: magnesium alloy with manganese, which colours well, is sometimes used for small items where aesthetics and low weight are important.

However, when selecting magnesium alloys, there is always a set of compromises. On the one hand, low weight offers enormous structural benefits, but on the other hand, corrosion resistance (especially in chloride environments), operating temperature, and manufacturing process safety (especially during machining and chip processing) must be carefully managed. Therefore, in practice, magnesium and its alloys are rarely a one-to-one ‘substitute’ for steel or aluminium – they are usually a deliberate choice, justified by a balance of weight, technology, and environmental conditions.

Magnesium and its alloys – summary

Magnesium is a unique material primarily because, as an engineering metal, it has the lowest specific weight, making its alloys a natural choice in designs where weight is a key constraint. At the same time, pure magnesium has poor mechanical properties and limited plasticity at room temperature, which is why magnesium alloys are of primary industrial importance. The most important alloying additives – aluminium, zinc, and manganese – increase strength, and manganese additionally improves corrosion resistance; the decrease in the solubility of these components with temperature enables dispersion hardening through supersaturation and ageing, although the effect is usually less than in aluminium alloys. Technologically, alloys are divided into cast and wrought, with the latter requiring hot working (with tool heating), but capable of achieving very favourable levels of strength and ductility. In applications ranging from aerospace to automotive, magnesium wins in terms of ‘weight’, but requires a conscious approach to corrosion, process safety, and the selection of manufacturing technologies.