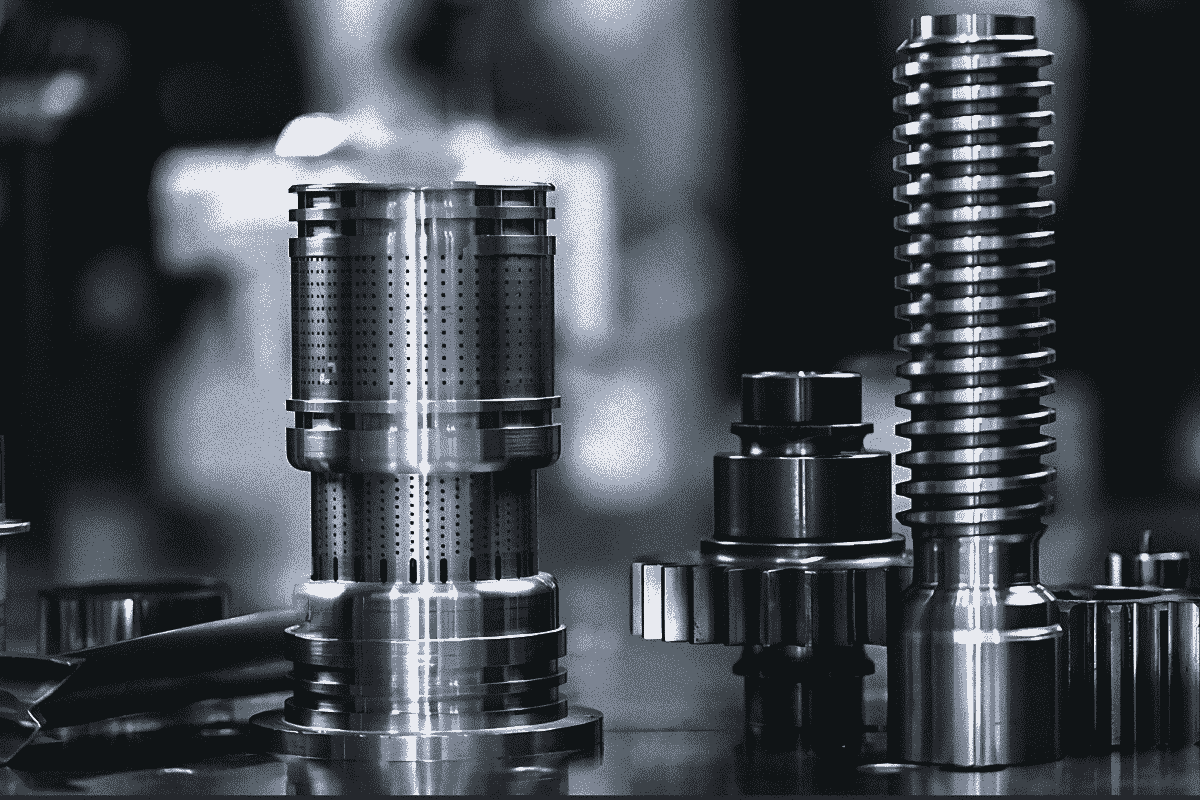

Structural alloy steels

Table of contents

Structural alloy steels are steels intended for machine and equipment components that operate in conditions considered typical for structural mechanics, i.e., at temperatures ranging from approximately –40°C to 300°C and in environments that are not particularly chemically aggressive. In practice, this means that where mechanical loads dominate, and the environment does not require corrosion resistance or heat resistance, the basic selection criterion is a set of mechanical properties rather than ‘special’ properties.

The most frequently required parameter is not ‘tensile strength’ itself, but high yield strength, as this determines whether the component will begin to deform permanently under working load. At the same time, structural elements rarely operate in perfectly static conditions – in reality, variable loads, impacts, and vibrations occur, which is why fatigue strength and resistance to brittle fracture are very important. In this context, an important concept is the ductile-brittle transition temperature (Tpk), because at low temperatures, steel can behave much more brittle, and then even local stress concentrations (e.g., notches, cross-section transitions, surface defects) become dangerous. If a component is to operate under friction and sliding or rolling contacts, there is a requirement for high hardness and wear resistance, usually achieved by producing a hard surface layer while maintaining a ductile core.

This is where we can see why alloy steels are so often chosen over carbon steels. Carbon steel can achieve high hardness after hardening, but its main limitation is its low hardenability, which means that with larger cross-sections (the material specifies a limit of approximately 25 mm), a uniform hardened state cannot be achieved across the cross-section. As a result, after subsequent tempering, the component has different properties at the surface and in the core, which is particularly disadvantageous in dynamically loaded structures. Alloy steel, thanks to additives, allows for a more ‘predictable’ and uniform response of the material throughout the entire cross-section of the component.

Why alloying works

In structural steels, alloying is a tool that primarily changes the kinetics of austenite transformations and thus influences the structure obtained after cooling. The most important practical effect is an increase in hardenability, i.e., the ability of steel to form hardening structures (martensitic or bainitic) not only at the surface but also deep within the material. In practice, this has two key effects. Firstly, it allows larger components to be hardened in milder cooling media (e.g., in oil instead of water), which reduces the risk of cracks and limits deformation. Secondly, it allows for through-hardening after quenching and tempering, i.e., a set of core and surface properties that is consistent throughout the cross-section.

The second important mechanism is the effect of additives on the fragmentation of structural components and on the behaviour of steel during tempering. A finer structure after the transformation of supercooled austenite usually means higher strength while maintaining better fracture resistance. At the same time, many alloying additives cause the steel to ‘retain’ its beneficial properties during tempering and not lose them so easily, as the softening processes are delayed or require a higher temperature. This is important because in machine designs it is not about maximum hardness, but about a lasting compromise: high yield strength + impact strength + stability of properties.

For this reason, alloy steels very often work in a heat-treated state. The chemical composition alone rarely ‘does the job’. If steel is to function as a highly reliable structural material, in practice, the entire package is designed: steel selection + process selection (normalising, heat treatment, carburising, nitriding, surface hardening) + selection of cooling and tempering parameters. Only then does alloying become real ‘structure control’ and not just the addition of elements to the chemical analysis.

Low-alloy steels with increased strength

Low-alloy steels with increased strength, which are often used in a normalised state, occupy an important place among structural alloy steels. Their specificity lies in the fact that they must combine increased yield strength (the material indicates a range of approximately 300-460 MPa) with practical weldability. In order to maintain weldability, the carbon content is limited – the material specifies that it does not exceed approx. 0.22%. This is very important: in this group, the aim is not to increase properties by ‘raising carbon’, but by controlling the structure and using moderate alloying additives.

In the normalised state, there are two ‘models’ of microstructure. The first is pearlitic steels with a ferritic-pearlitic structure, where alloying elements are present in the solid solution in ferrite or are part of carbides in pearlite. The increase in strength compared to carbon steels with similar carbon content is due to the fact that the additives harden the ferrite, promote a higher proportion of harder components, and support grain refinement. The typical additives in this group are primarily manganese, copper, silicon, and aluminium, and in some varieties also vanadium and niobium; typical ranges are also given, including manganese in the range of 1.0–1.8% and silicon in the range of 0.20–0.60%.

The second model is bainitic steels, which in a normalised state obtain a bainitic structure thanks to a set of additives that delay diffusion transformations and promote the formation of bainite during cooling. The material notes that this group may contain small amounts of additives such as molybdenum and boron, as well as additives that affect the kinetics of transformations, such as manganese and chromium, which allows very high strength levels to be achieved even when cooled in air (the material gives a range of 1100–1200 MPa). This shows the logic of this family of materials: weldability is maintained thanks to low carbon content, and the ‘strength’ is provided by the structure obtained by normalising, supported by appropriate alloying.

Steels for carburising and surface hardening

Steels for carburising are selected primarily on the basis that the component is to have a very hard surface layer, while the core should retain ductility and resistance to cracking. Therefore, these are steels with a low carbon content in the core; the material is typically in the range of approximately 0.14-0.25% C. The technological rationale is simple: the core remains ‘soft’ (less brittle), and high hardness only appears in the surface zone, where carbon has been introduced during the carburising process, and this layer is then hardened.

It is possible to carburise carbon steels, but the material emphasises that this solution makes sense mainly for small components with small cross-sections or where abrasion resistance is important but high core strength is not required. With larger cross-sections, carbon steel can provide a hard surface, but the core does not achieve the desired strength because the component does not harden in cross-section. Furthermore, to ensure the hardness of the layer in carbon steel, more rapid cooling is often required, which increases deformation and the risk of cracks.

Therefore, in practice, alloy steels for carburising dominate, as alloy additives provide greater hardenability and allow for favourable properties not only of the layer but also of the core, often when hardened in oil. The material draws attention to an important limit: excessive alloying, especially in a layer with an increased carbon content, can promote the formation of more residual austenite, which in turn can reduce the hardness of the carburised layer. This is an important practical conclusion, as it shows that carburising is not about maximising additives, but about their optimal selection.

The article emphasises the role of chromium, which is present in virtually all steels for carburising, usually in amounts of 1-2%, as it effectively increases hardenability and facilitates the formation of a hard layer during oil cooling. Further improvement in hardenability and core properties is achieved by adding nickel, which is why important components are often made of chromium-nickel steels. At the same time, it is pointed out that nickel is a scarce component, so its use is justified by operational requirements rather than ‘custom’. In practice, manganese solutions are also used, but then it is necessary to control adverse phenomena (e.g., concerning grain), and additives such as molybdenum or titanium are used as aids to improve properties and promote fragmentation.

Steels for surface hardening are selected using a similar logic, where the aim is to achieve a hard surface with a strong core. The material often indicates a carbon content range of 0.4-0.6% for steels used for this type of treatment, and in the case of higher requirements for core properties (especially in larger cross-sections), the practice is to first perform heat treatment of the entire element and only then surface hardening.

Steels for heat treatment and specialised groups

Steels for heat treatment are designed to achieve a very favourable compromise after hardening and high tempering: high strength and yield strength while maintaining ductility and impact strength.

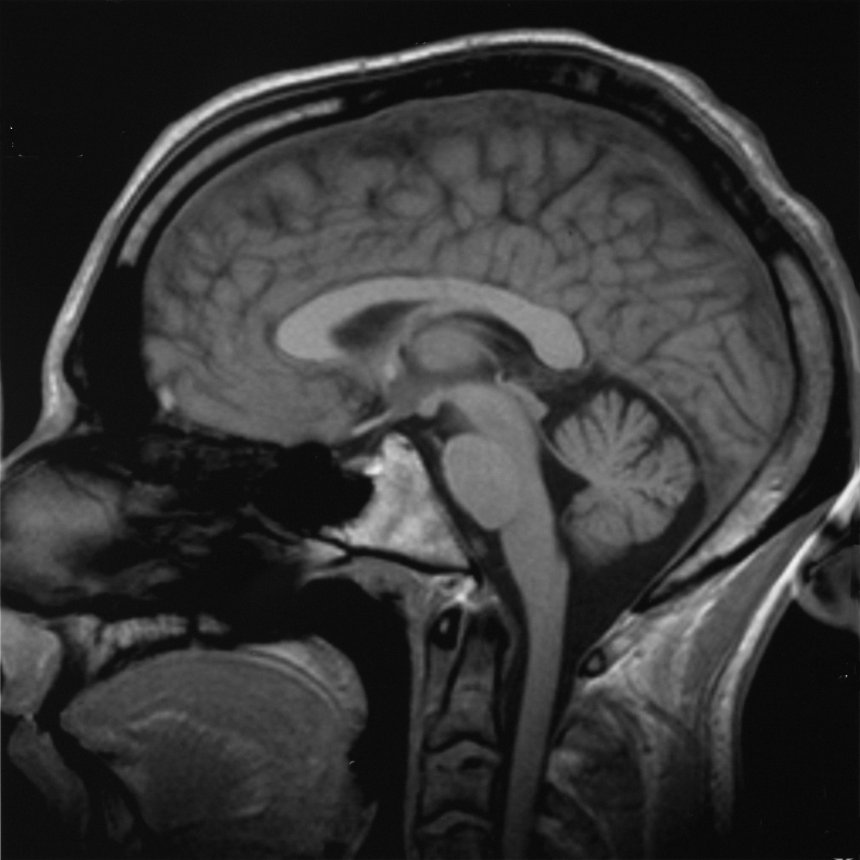

Heat treatment (hardening + high tempering) leads to sorbite structures and is the basic way to obtain high properties in machine components. The material states that typical tempering temperatures are in the range of approximately 500–700°C, and property levels can reach Rm 750–1500 MPa and Re 550–1350 MPa. It is also crucial that alloy steel allows this state to be achieved throughout with larger cross-sections, while carbon steels are usually sufficient mainly for cross-sections up to about 20–25 mm.

In this group of process parameters, the selection is not made ‘blindly’, because tempering is a compromise: a higher temperature usually improves plasticity at the expense of strength, while a lower temperature gives higher strength at the expense of greater sensitivity to cracking. The material also highlights the phenomenon of temper brittleness, which manifests itself in decreases in impact strength in certain temperature ranges. A characteristic decrease around 300°C and a second decrease above 500°C have been identified, whereby in the latter case it is practically important that the cooling rate after tempering is significant: accelerated cooling (e.g., in water or oil) can reduce the adverse effect compared to slow cooling. This shows that the ‘tempering temperature’ is not the only variable – the way the process is completed is also important.

With regard to alloying in steels for heat treatment, the material emphasises the role of additives such as chromium (increases hardenability and affects tempering behaviour), molybdenum (helps to reduce some adverse effects, including the tendency to temper brittleness, and increases hardenability) and nickel, which is particularly valuable because it increases hardenability and improves plastic properties, and additionally lowers the ductile-brittle transition temperature, which is important when working at reduced temperatures.

The material indicates that chromium-nickel steels are among the best in this group, although they require control of tempering-related phenomena, hence the practice of adding molybdenum and sometimes also vanadium.

Apart from steels for strengthening, there are groups of structural alloy steels with a fairly clearly defined function. Steels for nitriding are selected to produce a hard layer of nitrides; therefore, additives such as aluminium, chromium, and molybdenum are used, and the process is usually preceded by heat treatment, with the tempering temperature having to be higher than the nitriding temperature so that the core does not change its structure during nitriding itself. Spring steels are designed for high elastic limit and fatigue life; the material emphasises the role of silicon and the importance of surface quality (oxidation and decarburisation severely impair fatigue life), and typical processing includes hardening and tempering to maintain high strength. Bearing steels must provide very high hardness and resistance to abrasion and contact pressures, and the material refers to typical high-carbon, high-chromium steel and typical processing: oil hardening and low tempering at around 180°C to obtain fine-grained structures with fine carbides.

The material also indicates more specialised solutions, but still within the ‘structural’ field in the broad sense. Maraging steels (iron alloys with nickel) form ductile martensite after hardening and only achieve high strength after ageing, when intermetallic phase precipitates appear; this is the path to exceptional properties at the cost of a high price. In turn, heat and plastic treatment combine the plastic deformation of austenite with hardening, so that martensite ‘inherits’ a denser dislocation structure and fragmentation, which results in a significant increase in strength (the material states that by as much as several to several dozen per cent), but makes subsequent machining difficult.

Alloy structural steels – summary

Alloy structural steels are used when it is necessary to obtain certain, repeatable mechanical properties under typical operating conditions and at the same time maintain the safety of the component under variable loads. Their advantage over carbon steels is mainly due to their greater hardenability, which allows heat treatment and shaping of properties on larger cross-sections, often with gentler cooling, and therefore with less risk of cracks and deformations. In practice, the selection of alloy structural steel is the selection of the entire system: composition + type of heat treatment (normalising, refining, carburising, nitriding, surface hardening) + process parameters, because only this set determines the microstructure, and the microstructure determines the properties.

Within this group, the following stand out: low-alloy normalised steels (where weldability and yield strength are key), steels for carburising and surface hardening (where a hard layer and ductile core are important, with control of phenomena such as residual austenite), steels for heat treatment (where the compromise between properties and conscious selection of tempering, including consideration of temper brittleness, is critical), and specialised groups such as steels for nitriding, spring and bearing steels.