Ceramics as a biomedical material

Table of contents

Ceramics are commonly associated with porcelain, glass, or architectural elements. In biomedical engineering, however, the term has a much broader meaning. Ceramics are inorganic, non-metallic materials whose main components are usually metal oxides, silicates, carbides, or nitrides. They are characterised by high hardness, high compressive strength, high melting point, and very low electrical and thermal conductivity. At the atomic level, their properties result mainly from the predominance of ionic or covalent bonds and the limited number of possible slip planes in the crystal lattice. This is why ceramics, unlike metals, do not undergo easy plastic deformation.

The main consequence of this structure is fragility. Ceramics tend to crack in the presence of microcracks, inclusions, or sharp notches. Instead of gradually deforming, as metals do, they break suddenly and relatively violently when the stress near an existing defect exceeds a critical value. This explains why their tensile strength is much lower than their compressive strength. Interestingly, under ideal conditions, when the material is virtually defect-free, ceramics can be extremely strong – an example is glass microfibres with a tensile strength of several gigapascals, exceeding the strength of many high-strength steels.

Ceramics are also materials that practically do not creep at room temperature. While metals can gradually deform under prolonged stress, ceramics, due to their rigid bond structure, retain their dimensionality until a crack initiates. This feature is both an advantage when we think about stable load transfer and a disadvantage, because the inability to “release” stresses through plastic deformation promotes sudden fractures.

The field of bioceramics was born when ceramics began to be consciously used for contact with body tissues. It turned out that appropriately selected ceramic compositions can be used not only in electronics or high-temperature industries, but also to replace bone fragments, rebuild teeth, construct joint implants, and even elements that come into contact with blood, such as artificial heart valves. However, several basic biological criteria must be met.

In order for a ceramic material to be considered bioceramic, it must be non-toxic, non-carcinogenic, non-allergenic, should not cause chronic inflammatory reactions, and must be biocompatible and retain its biofunctionality throughout the entire expected implantation period. In other words, it must not cause harm, must fulfil its mechanical or biological function, and should not degrade unpredictably.

On this basis, bioceramics are divided into three main classes. The first class consists of non-absorbable ceramics, i.e., relatively biocompatible ceramics, which, after implantation, practically do not dissolve or undergo significant structural changes and are designed to serve for many years. The second group consists of biodegradable (resorbable) ceramics, which are designed to be gradually replaced by the host’s growing tissue. The third category consists of bioactive, surface-reactive bioceramics, whose task is to form a strong chemical bond with bone or other tissue, primarily through reactions that occur only in the surface zone.

Relatively biocompatible bioceramics

Relatively biocompatible bioceramics retain their physical and mechanical properties during long-term use in the body. They do not dissolve to any significant extent, are resistant to corrosion and wear, and contact with tissues usually boils down to mechanical adaptation or integration without significant chemical reactions. Aluminium oxide, zirconium oxide, and various types of carbon, including pyrolytic carbon, are particularly important in this group.

Aluminium oxide, also known as alumina (Al₂O₃), is one of the most commonly used ceramic materials in implantology. In biomedical applications, a high-purity alpha variety is used, in which the Al₂O₃ content exceeds 99.5% and the amount of impurities, such as silica and alkali oxides, is limited to tenths of a percent. Alumina has a rhombohedral crystal structure and occurs naturally as sapphire or ruby, depending on the colour-giving impurities present. Single-crystal forms of this material can be obtained by gradually melting powder on a crystal seed, from which the growing crystal is “pulled”.

The mechanical properties of alumina are impressive. Its Young’s modulus reaches several hundred gigapascals, its flexural strength exceeds 400 MPa, and its hardness ranges from 20 to 30 GPa. The latter value means that aluminium oxide ranks very high on the Mohs scale (9/10), second only to diamond. However, the strength and reliability of polycrystalline alumina depend significantly on grain size and porosity. Reducing porosity and using a fine-grained structure increases strength and reduces the spread of results.

This combination of hardness, wear resistance, and chemical inertness in the body environment makes alumina the material of choice for the construction of sliding elements in joint endoprostheses, especially hip prosthesis heads that interact with ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene cups. Studies of aluminium oxide implants inserted into the skull have shown no toxicity, no signs of rejection, and very good tolerance over long periods of observation. Alumina has also found application in dental implants, bone plates and screws, middle ear reconstructions, and components requiring high hardness and chemical inertness.

The second key material in this group is zirconium oxide (ZrO₂). In its pure form, it has a complex phase diagram – at different temperatures, it takes on different crystal structures, accompanied by significant changes in volume. Such variability is unfavourable from the point of view of dimensional stability, which is why zirconia partially stabilised with oxides such as Y₂O₃ is used in practice. Thanks to such additives, it is possible to stabilise high-temperature phases (tetragonal or cubic) also at lower temperatures, which improves the stability of the structure after sintering.

Partially stabilised zirconia has a lower modulus of elasticity than alumina, which makes it slightly more similar to bone, while also exhibiting particularly good resistance to fracture. This is due to the mechanism of transformational strengthening – a local phase transition occurs near the propagating fracture, accompanied by a slight increase in volume, which “closes” the fracture and hinders its further growth. The biocompatibility of zirconia is very good, and its friction and wear parameters when used with UHMWPE are so favourable that this material has found application in joint endoprosthesis heads and other load-bearing elements.

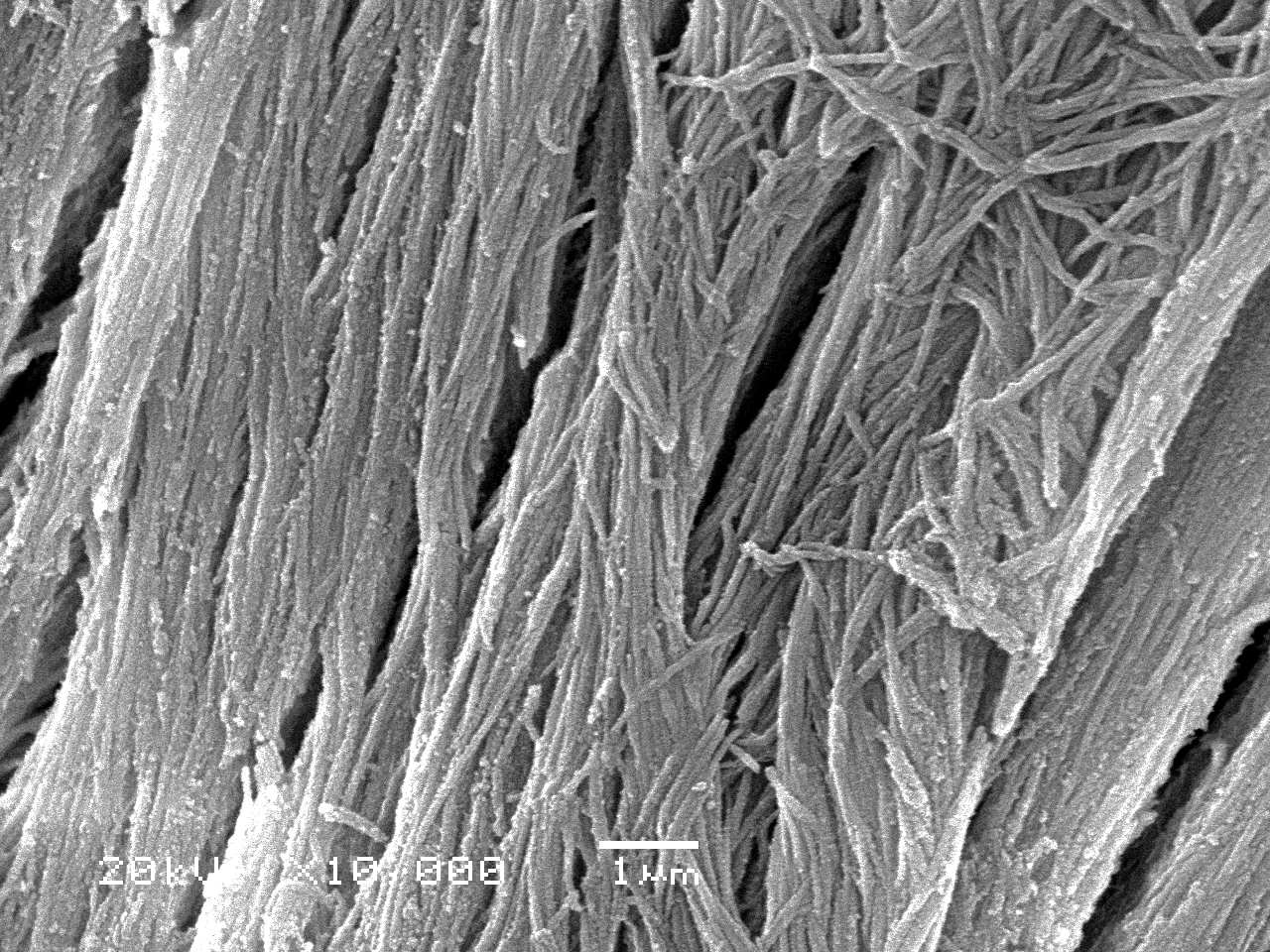

Various forms of carbon play a special role among bio-inert ceramics. The crystal structure of graphite, a classic form of carbon, consists of flat, hexagonal networks of atoms connected by strong covalent bonds, arranged in layers. Weaker interactions occur between the layers, which facilitates their movement relative to each other and explains the lubricity of graphite. In materials such as pyrolytic carbon or vitreous carbon, these hexagonal layers are partially disturbed, deformed, and mixed with amorphous areas. On a macro scale, this leads to more isotropic mechanical properties.

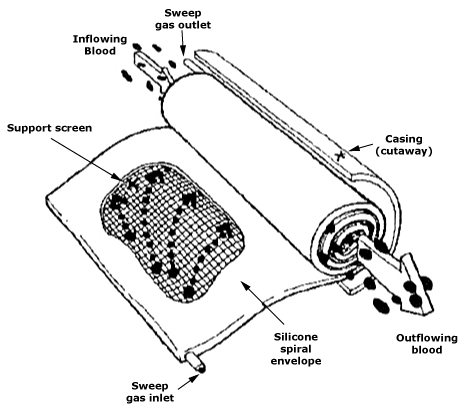

Pyrolytic carbon is particularly valuable in implantology, as it is characterised by high strength, decent elastic modulus, and excellent blood compatibility. This material is most often used as a coating applied from the gas phase to the final shapes of implants, e.g., heart valve components or vascular prostheses. Process parameters such as temperature, pressure, gas composition, reactor geometry, and deposition time allow for very precise adjustment of the density, anisotropy, crystallite size, and presence of defects in the carbon. Higher density usually means higher strength and elastic modulus, which is crucial for the long-term safety of implants.

There are also carbon-carbon composites, in which carbon fibres reinforce the carbon matrix. They achieve very high strength along the direction of the fibres, but are distinctly anisotropic and porous. From a mechanical point of view, they may be attractive, but their use requires extremely careful planning of load distribution in the body.

Biodegradable bioceramics

In many applications, the goal is not to permanently replace tissue, but to temporarily fill a defect, provide mechanical support, or deliver a drug, after which the implant should gradually be replaced by regenerating host tissue. In such situations, resorbable ceramics, which degrade in a controlled manner, are the ideal choice.

Historically, one of the first materials of this type was plaster, or calcium sulphate dihydrate, which was already being used at the end of the 19th century as a bone substitute. However, the real breakthrough came in the second half of the 20th century, when fully synthetic calcium phosphates and more complex systems such as aluminium-calcium-phosphate ceramics (ALCAP), zinc-calcium-phosphate (ZCAP), zinc-sulphate-calcium-phosphate (ZSCAP), and iron-calcium-phosphate (FECAP).

The most important representative of this group is hydroxyapatite (HA), chemically similar to the mineral phase of bones and teeth. It has a formula similar to Ca₁₀(PO₄)₆(OH)₂ and belongs to the apatite family. Structurally, it forms hexagonal prisms in which hydroxyl ions are arranged in columns along the c-axis, and some of the calcium ions are strongly bound to them. The remaining Ca²⁺ ions complete the crystal lattice, ensuring the stability of the structure. The molar ratio of calcium to phosphorus is 10:6, and the theoretical density is close to 3.2 g/cm³. The replacement of OH⁻ ions with F⁻ ions results in increased chemical stability, which explains why fluoridation strengthens tooth enamel.

Hydroxyapatite is a material with exceptional biocompatibility, as its structure and chemical composition closely resemble those of natural bone tissue. After implantation in the form of granules or porous blocks, new cancellous bone is quickly formed, and the boundary between the implant and the bone often takes the form of a direct chemical bond, without a distinct fibrous zone.

The mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite can vary significantly depending on the manufacturing method, grain size, and porosity. The modulus of elasticity can reach a value comparable to that of natural hard tissues such as enamel, dentine, or compact bone. This allows the design of implants whose stiffness is matched to the surrounding tissue, reducing the risk of the adverse phenomenon known as stress shielding, i.e, unloading and gradual bone loss.

In addition to hydroxyapatite, β-calcium triphosphate (β-TCP) plays an important role. It is more soluble than HA, which results in faster resorption in vivo, while maintaining good osteoconductivity. This makes the material well-suited as a temporary bone defect filler, which gradually disappears as the patient’s own bone grows. Like hydroxyapatite, TCP is often produced by wet synthesis from appropriate calcium and phosphate salts, followed by calcination and sintering. It can form composites with amino acids such as cysteine, which, when mixed with water, bind and harden at the implantation site, allowing the material to form directly in the defect.

More complex ceramic systems, such as ALCAP, ZCAP, ZSCAP, and FECAP, are usually polyphase. This means that their structure contains several different crystalline phases with varying solubility and resorption rates. This structure allows for the design of materials that degrade in multiple stages: some phases disappear faster, others slower, and during this process, biologically important ions, such as zinc or iron, are released. They can also be used as drug carriers – the active substance is enclosed in a ceramic matrix and gradually released as the implant resorbs.

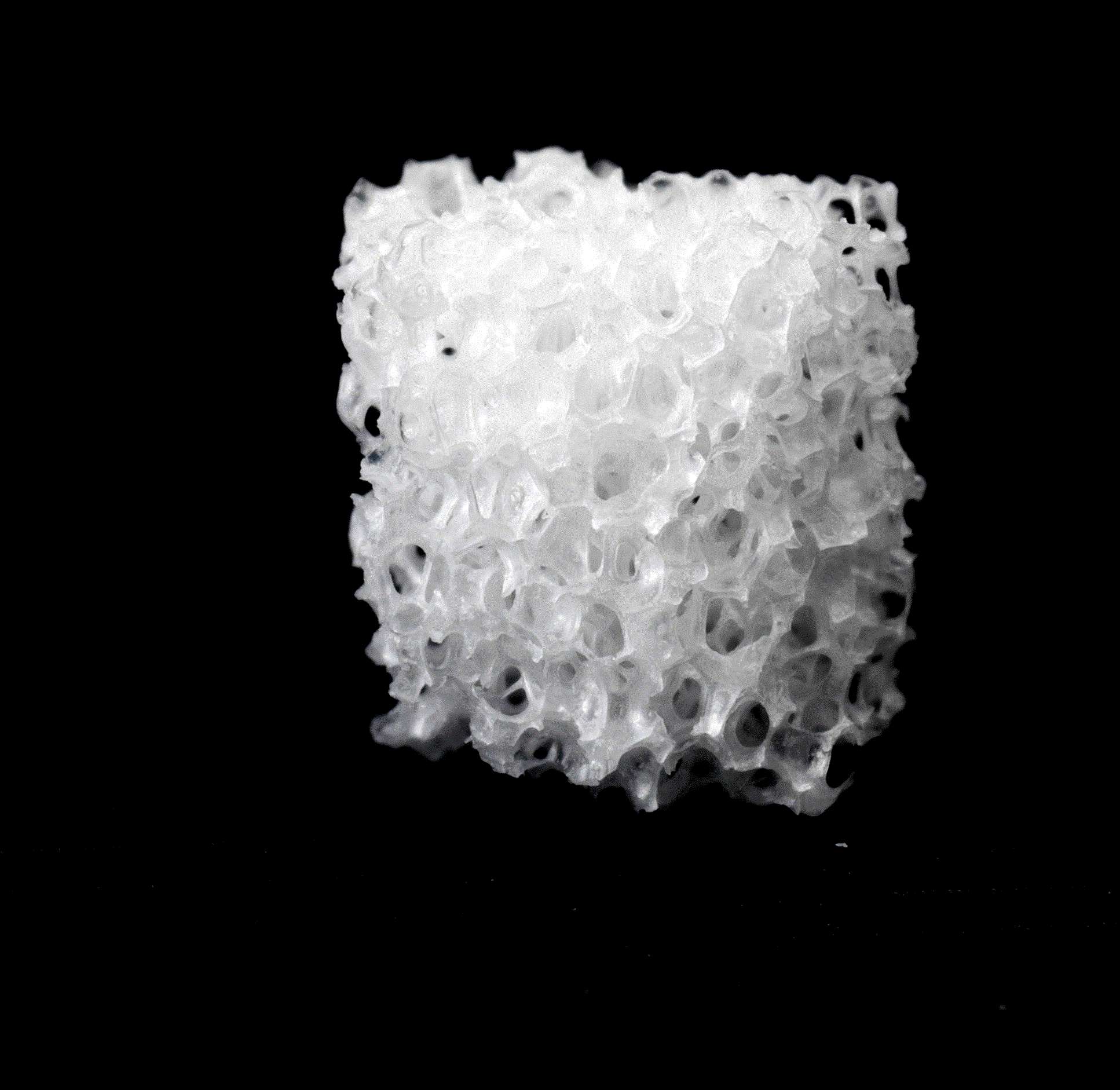

An interesting example of a naturally occurring resorbable material is corallina, i.e., the skeleton of corals, composed mainly of calcium carbonate in the form of aragonite. Individual coral species form unique, three-dimensional porous structures that resemble trabecular bone in terms of size and pore distribution. This makes materials such as Biocoral ideal for filling bone defects. Calcium carbonate undergoes gradual resorption and is replaced by bone. In addition, coral skeletons can be hydrothermally converted into hydroxyapatite while retaining their natural pore architecture, combining the advantages of close chemical similarity to bone with a very favourable spatial microstructure.

Bioactive surface-reactive bioceramics

Between extremely inert ceramics and more rapidly resorbable materials, there is a third, extremely important group – bioactive bioceramics, i.e., surface-reactive glasses, glass-ceramics, and certain forms of hydroxyapatite. Their special feature is that, although the bulk volume of the material remains relatively stable, the surface actively reacts with body fluids, forming a layer that can create a strong chemical bond with bone.

A classic example is bioactive silicate glasses, such as materials from the Bioglass family, and their crystallised counterparts – glass-ceramics. These systems are based on silica (SiO₂) with additives of calcium oxide, sodium oxide, and phosphorus(V) oxide. After implantation into the body, a series of reactions takes place on the surface of such materials: first, Na⁺ and Ca²⁺ ions are exchanged with the environment, causing a local change in pH and ionic activity. Next, a gel layer rich in silica is formed, on which calcium phosphates precipitate, which over time transform into a structure similar to apatite. This surface apatite layer allows the bone to anchor directly into the glass, without the mediation of fibrous tissue.

The bioactivity of glass is strongly dependent on its chemical composition, primarily the SiO₂ content and the proportions of CaO, Na₂O, and P₂O₅. There is a specific range of composition in which both a silica and phosphate layer are formed simultaneously. Outside this range, the material is either too unreactive to form a durable bond with tissue or too susceptible to dissolution.

Glass-ceramics, such as crystallised Bioglass or Ceravital forms, are produced as a result of controlled glass crystallisation. During production, the material undergoes a sequence of heat treatments, which lead to the formation of a huge number of tiny crystallites (with diameters of a fraction of a micrometre) evenly distributed throughout the volume. As a result, glass-ceramics combine high density, high strength, good scratch resistance, and appropriate thermal properties. A carefully selected composition allows bioactivity to be maintained while improving mechanical parameters compared to purely amorphous glass.

Despite these advantages, bioactive glass and glass ceramics remain relatively brittle materials. Their tensile strength, although improved, is still too low to be used as standalone components in large, load-bearing implants such as joint prosthesis stems. However, they are widely used as coatings on metal implants, where they form a direct connection with the bone, and as fillers in dental composites, materials for middle ear reconstruction, and small cranial implants.

Deterioration and fatigue of ceramics in the body

When designing ceramic implants, it is important to consider not only the properties of the material immediately after manufacture, but also how these properties change over time under the influence of the biological environment and mechanical loads.

In non-absorbent ceramics, static and dynamic fatigue play a significant role. In an aquatic environment, which corresponds to physiological conditions, water can accelerate the growth of existing microcracks. If the material contains additives that facilitate water penetration, this can lead to a gradual reduction in strength under prolonged loading, even if the stresses are lower than the strength limit determined in a short-term test. This phenomenon has been studied in detail in aluminium oxide, among other materials, observing the relationship between the presence of traces of water action on the fracture surface and the decrease in strength.

Statistical strength models, such as the Weibull distribution, are often used to describe the behaviour of ceramics, in which the probability of failure depends on a constant scale and shape parameter m. The higher the value of parameter m, the smaller the strength dispersion and the greater the predictability of the material’s behaviour, which is crucial in the design of implant components. Proof tests, in which finished components are subjected to stresses higher than the expected operating loads, are also a practical reliability engineering tool. Weaker specimens are destroyed during testing, and for the remaining ones, the minimum expected lifetime at a given load level can be determined.

In the case of carbon coatings on metals, fatigue tests have shown that the integrity of the coating is strongly dependent on the behaviour of the substrate. If the metal substrate does not undergo significant plastic deformation, pyrolytic carbon can remain intact even with a very high number of load cycles, which is particularly important for coated heart valves or vascular prostheses.

Bioceramic manufacturing techniques

The choice of bioceramic manufacturing technique depends largely on the intended use of the implant. If the aim is to replace hard tissue and transfer mechanical loads, high density, high strength, and an appropriate modulus of elasticity will be the priority. In applications where tissue integration and intensive vascularisation are most important, high open porosity and the right pore size distribution play a key role.

Supporting implants use techniques such as injection moulding, gel casting, and microemulsion methods, which enable high density (above 97–99% of theoretical density) to be achieved with relatively low porosity. Appropriately selected additives, including sodium phosphates, lithium or partially stabilised zirconia, can improve sinterability, increase microhardness and fracture resistance, and influence microstructure development during sintering. It should always be borne in mind that too many additives or their inappropriate selection can lead to the formation of non-biocompatible or overly soluble phases.

If the goal is rapid integration with bone and other tissues, ceramics are designed to have high open porosity, with pores of a diameter that allows blood vessels and cells to penetrate (usually at least several dozen micrometres). Here, among other things, the starch consolidation method is used, in which starch granules are mixed with a ceramic suspension and then swell during drying. During sintering, the starch burns away, leaving pores in its place. By adjusting the proportion of starch in the mixture, it is possible to precisely control the final porosity and pore size distribution, obtaining structures with pores ranging from a few micrometres to tens of micrometres.

Another technique is drip casting, in which drops or granules are formed from a hydroxyapatite suspension, for example, by dripping them onto special moulds or into liquid nitrogen. After drying, calcination, and sintering, porous HA granules are obtained, which can be used as bone defect fillers. Regardless of the details of the process, the goal is to create a structure that is strong enough to survive implantation and the early healing phase, while providing a high degree of tissue penetration.

Summary – Ceramics as a biomedical material

Bioceramics are currently one of the key groups of biomaterials used in medicine. They include relatively bio-inert oxide ceramics, such as alumina and zirconia, as well as resorbable calcium phosphates, coral-based structures, multi-component systems containing zinc or iron, and bioactive glasses and glass-ceramics. Each of these materials has its own “role” to play in the body: some are intended to be stable, long-lasting bone replacements, others to gradually give way to new tissue, and still others to provide a strong chemical anchor for implants in bone.

The key to designing bioceramics is understanding the relationship between chemical composition, crystal structure, microstructure, manufacturing method, and behaviour in a biological environment. Modern implants very often combine different materials: metal for load-bearing, bioactive ceramics for a durable bond with bone, resorbable scaffolds to support regeneration, and carbon coatings in components that come into contact with blood. Bioceramics are no longer just a “hard material” – today, they are a precisely designed tool for tissue engineering and implantology, allowing for increasingly better imitation of the biological functions and structure of the body’s tissues.