Phase equilibrium systems of alloys

Table of contents

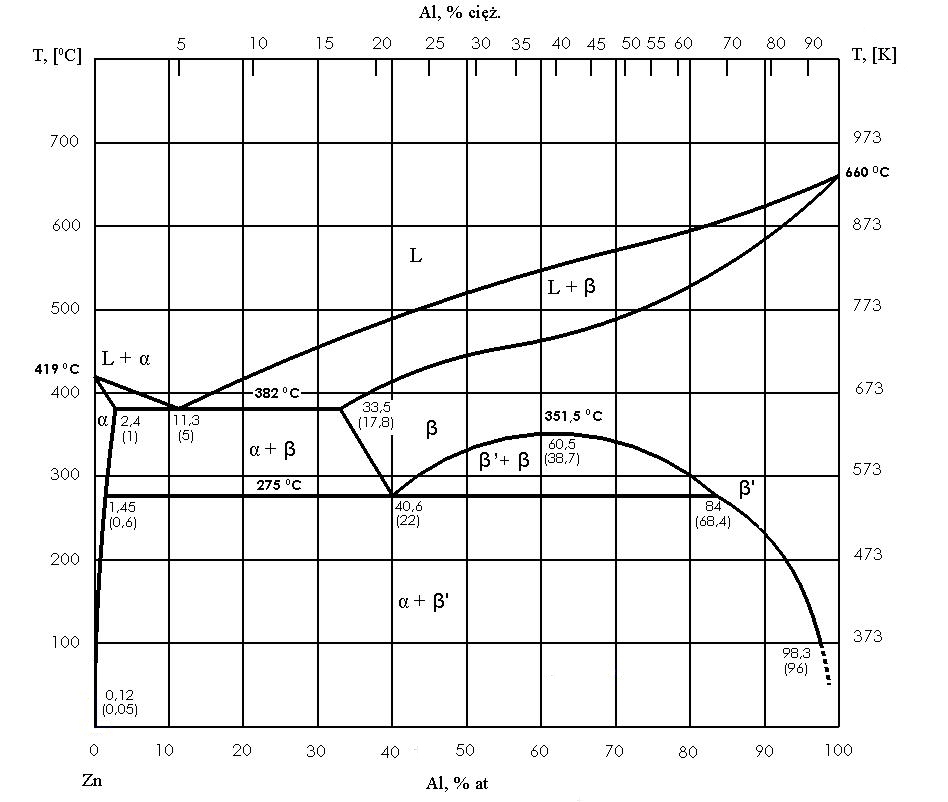

In pure metals, the course of transformations is usually easy to grasp: melting and solidification occur at a single, precisely defined temperature, as do some structural transformations in the solid state. Cooling curves then show characteristic pauses, because energy is absorbed or released for the transformation itself, rather than for the temperature change. In the case of alloys, the situation is no longer so ‘point-like’. It often happens that an alloy begins to solidify at one temperature but ends at another, and during the process, phases with varying compositions coexist.

This is why phase equilibrium diagrams, also known as phase diagrams, are used in materials science. Such a diagram can be treated as a map: it shows which phases are stable depending on temperature and composition, and in what order the transformations occur during heating and cooling. This makes it possible to predict both the course of crystallisation and subsequent transformations in the solid state, and, as a consequence, the structure and properties of the finished alloy.

Key concepts: system, phase, and components

To read equilibrium diagrams correctly, you need to understand the language they ‘speak’. In thermodynamic terms, a system is a separate fragment of reality analysed under given conditions, for example, a sample of alloy that we are cooling. A phase means a homogeneous part of a system with identical properties and a constant chemical composition, separated from other phases by a phase boundary. A phase can be a liquid, a solid solution, or a specific intermetallic phase, if one is formed.

The constituents, i.e., the substances (usually elements) that make up the alloy and from which phases can form, are also important. In the context of binary diagrams, we usually refer to a system composed of two constituents whose proportions vary in the alloy. In practice, this means that the diagram does not describe a single ‘material’, but rather a whole family of alloys with different compositions, and each change in composition moves us to a different place on the phase map.

Gibbs phase rule

One of the reasons why the behaviour of alloys differs from that of pure metals is the number of variables that ‘control’ the system. Gibbs’ phase rule organises the relationship between the number of components, the number of phases, and the number of degrees of freedom. In metallurgical practice, constant pressure is often assumed because its effect on metal phase transitions is usually small compared to the effect of temperature and composition.

The practical sense is this: if the system has little ‘room for manoeuvre’, the transition must occur at one temperature (hence the characteristic stops). However, when there is variability in composition and the possibility of several phases coexisting, the system may pass through areas where two phases occur simultaneously, and their compositions change with temperature. Then, solidification or solid-state transformations extend over a certain temperature range, and the structure is formed in stages.

How is a binary equilibrium diagram created?

A typical binary diagram shows the relationship between temperature and chemical composition. The horizontal axis represents the composition of the alloy (e.g., the percentage of one component), and the vertical axis represents the temperature. To construct such a diagram, a series of experiments is performed for many alloys with different proportions of components, and the temperatures at which the transformations occur are recorded – most often by thermal analysis methods, based on cooling and heating curves.

The boundaries of the phase areas are particularly important in the graph. A line called the liquidus separates the completely liquid area from the area where the liquid coexists with the solid phase. The solidus line marks the boundary below which the alloy is completely solid. Between the liquidus and the solidus, there is usually a mixture area (e.g., liquid + solid phase), which in practice means that during cooling, the alloy goes through a stage where part of the material is already solid, and part remains liquid.

It is also important how the composition of the phases at a given temperature is read. This is done by drawing a horizontal line (isotherm) through the graph: the intersection with the liquidus shows the composition of the liquid, and the intersection with the solidus shows the composition of the solid phase in equilibrium at that temperature. This is the basis for inferring what is actually happening in the alloy during cooling.

The most important types of equilibrium systems

Continuous solid solution

In some systems, the components mix freely with each other in both the liquid and solid states. In this case, below the solidus, there is one phase – a solid solution with a composition depending on the position on the composition axis. During cooling, the alloy begins to solidify at the liquidus when the first crystals of the solid solution appear, and ends at the solidus when the last portion of liquid disappears. This is a classic example of solidification in a temperature range, without a single stop.

It is worth noting that in the ‘liquid + solid solution’ area, the compositions of both phases are different and change with temperature. Reading the isotherm allows us to determine which part of the alloy is already in a solid state at a given moment and which part is still liquid.

Eutectic

A eutectic system is very characteristic when the components mix in a liquid but dissolve poorly or not at all in a solid state. In this case, there is a eutectic composition and temperature at which a homogeneous liquid transforms into two solid phases at once. Such a transformation is isothermal, so there is a clear pause on the cooling curve, as in the case of pure metal, but the mechanism is different: instead of a single solid phase, a fine mixture of two phases is formed, usually with a specific, regular morphology.

Alloys with a composition other than eutectic form a mixed structure. If the alloy is hypereutectic, primary crystals of one phase are first separated, and only then does the rest of the liquid solidify as eutectic. If the alloy is hypereutectic, primary crystals of the second phase appear first, followed by the eutectic. As a result, the microstructure depends on the composition: the eutectic may dominate, the primary crystals may dominate, or both components may have similar proportions.

Eutectic with limited solubility in the solid state

In practice, an intermediate situation is often encountered: the components mix well in the liquid state, but in the solid state, they form solid solutions only to a limited extent. Then, instead of ‘pure’ phases, solid boundary solutions are formed, commonly denoted as α and β, and the eutectic becomes a mixture of these two solutions with saturated compositions at the eutectic temperature.

This is very important because, with further cooling, solubility in the solid state often decreases, so α and β solutions can become supersaturated. As a result, secondary separations and further ‘maturation’ of the structure may occur after solidification is complete. The diagram is therefore not only a description of crystallisation, but also a guide to the changes in the solid state that affect the properties of the material.

Peritectics

In peritectic systems, a transformation occurs in which the liquid reacts with the existing solid phase to form a new solid phase. This occurs at a specific temperature because three phases coexist at the moment of reaction. The peritectic mechanism is of practical importance because the new phase often grows on the crystals of the original phase, forming a layer that hinders further diffusion of the components. This can cause the actual course of the transformation to deviate from the ideal equilibrium, especially with faster cooling.

From a technological point of view, peritectics can be a source of heterogeneity and structures that depend not only on the equilibrium diagram itself, but also on kinetics, i.e., the speed of diffusion processes. Therefore, when interpreting diagrams, it is important to remember that the diagram describes equilibrium and not always the actual state ‘on the fly’ without time for the composition to equalise.

Limited solubility in liquid

Sometimes, even in a liquid state, the system is not completely homogeneous. It may happen that, within a certain temperature range, the liquid separates into two liquids with different compositions, which promotes segregation and the formation of areas with different properties. In such a system, a monotectic transformation is possible, in which one liquid transforms into another liquid and a solid phase.

From the point of view of casting technology, this is important because the separation of liquids can lead to undesirable heterogeneity of the alloy. In practice, this is often counteracted by appropriate process control, including the selection of the cooling rate or the method of mixing the liquid metal, in order to limit the time for segregation to develop.

Chemical compounds and intermetallic phases

In many systems, chemical compounds and intermetallic phases are formed. If a compound has a constant stoichiometric composition, it appears on the diagram as a characteristic position corresponding to this proportion of components. Such a compound may melt in a ‘pure metal-like’ manner when it transforms into a liquid of the same composition, or it may form and disappear in peritectic transformations when the process proceeds through reaction with the liquid.

Intermetallic phases are often hard and brittle, and their presence can significantly alter the properties of the alloy. For this reason, phase diagrams are particularly important in alloy design, as they allow us to predict whether, within a given range of composition and temperature, a phase will appear that will impair plasticity or, conversely, strengthen the alloy through fine precipitates.

Solid state transformations: eutectoid and peritectoid

Equilibrium diagrams do not end with solidification. In many alloys, transformations that occur after the transition to the solid state are important, especially when the solubility in solid solutions changes with temperature or when one of the components exhibits polymorphism. Of particular importance is the eutectoid transformation, which is equivalent to eutectics but occurs entirely in the solid state: one solid solution breaks down into two solid phases at a constant temperature. This transformation often leads to a fine, regular structure and can significantly alter mechanical properties.

There is also a peritectic transformation, analogous to peritectics, but without the involvement of liquid: two solid phases react to form a third solid phase. In practice, solid-state transformations can be crucial, as they can determine hardness, impact strength, or creep resistance, even if the solidification process has proceeded correctly.

Practical significance

The most important conclusion from the analysis of the diagrams is that the properties of alloys result primarily from their structure, and not only from the elements they contain. Single-phase alloys are usually more homogeneous, and their properties often change more smoothly with composition. In multiphase alloys, the situation is more complex because the behaviour of the material is determined by the type of phases, their proportion, distribution, grain size, and morphology (e.g., the form of eutectics or the nature of precipitates).

Therefore, a phase diagram is a tool that helps to link the process conditions to the result. If you know at what temperatures and compositions certain phases occur, you can consciously select the alloy composition and the cooling and heat treatment conditions. In practice, this means that it is possible to predict whether the alloy will tend to segregate, whether brittle intermetallic phases will appear, whether precipitates can be used for strengthening, or whether the structure will be stable under operating conditions.

Phase equilibrium systems of alloys – summary

Phase equilibrium systems are a tool that organises the behaviour of alloys systematically and predictably. They can be used to determine which phases will be stable, when solidification will begin and end, whether eutectic or peritectic phenomena will occur, and what transformations may take place in the solid state. In practice, this means the ability to control the microstructure and thus control the mechanical and physical properties of the material. The ability to read phase diagrams is therefore one of the most important skills in materials science and metallurgy, as it allows the theory of phase transformations to be translated into real engineering decisions.