Metallic biomaterials

Table of contents

Metals play a completely different role in biomedical engineering than ceramics or polymers. They are distinguished primarily by their excellent mechanical properties and high electrical and thermal conductivity. This is due to the nature of metallic bonding – some of the electrons are delocalised, forming a cloud of ‘free electrons’ which are responsible for conductivity and for the strong, albeit non-directional, bonding between metal ions. This structure enables atoms in the crystal lattice to move relative to each other without disrupting the order, resulting in the plasticity characteristic of metals and the ability to undergo large deformations without sudden destruction.

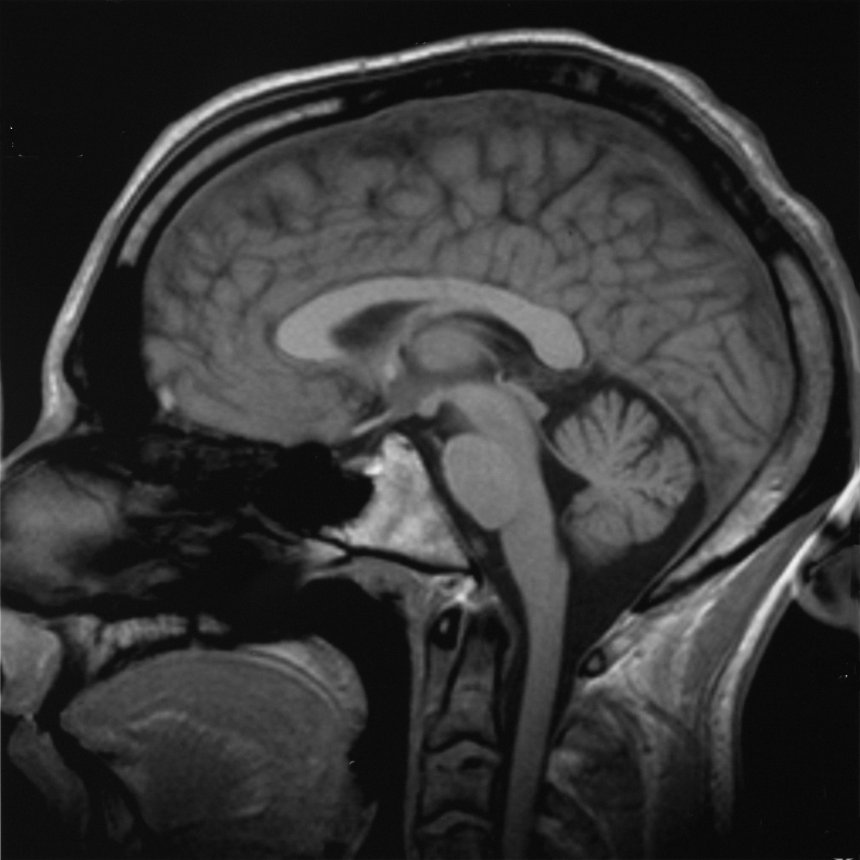

This feature is used very consciously in biomaterials. Metals serve both as passive replacements for hard tissue – in hip and knee prostheses, bone plates, screws, intramedullary nails, dental implants – and as materials for more ‘active’ devices such as vascular stents, catheter guides, orthodontic wires and cochlear implants. In these applications, it is not only strength that counts, but also formability, elasticity, conductivity and susceptibility to precision manufacturing.

The history of metallic biomaterials began with steel alloys. The first alloy developed specifically for orthopaedic applications was vanadium steel, used to manufacture plates and screws for fracture fixation (known as Sherman plates). Over time, it was replaced by stainless steels, and later by cobalt and chromium alloys and titanium alloys. These alloys use a number of metals – iron (Fe), chromium (Cr), cobalt (Co), nickel (Ni), titanium (Ti), tantalum (Ta), niobium (Nb), molybdenum (Mo) and tungsten (W) – which, as elements in larger doses, are toxic to the body, but in the form of stable, corrosion-resistant alloys can be well tolerated.

The key challenge in the use of metals is corrosion in the in vivo environment. Corrosion products can lead to both weakening of the implant itself and adverse biological reactions – local inflammation, tissue discolouration, organ damage or immune responses. Therefore, modern engineering of metallic biomaterials focuses on alloys capable of forming durable, passive protective layers on the surface and on conscious surface modification to combine good strength, high corrosion resistance and an appropriate biological response.

Stainless steels as implant materials

Stainless steel was one of the first materials to successfully replace vanadium steel in implants. Initially, 18-8 steel (type 302) was used, containing approximately 18% chromium and 8% nickel, with significantly better corrosion resistance than classic carbon steels. Over time, a variant of 18-8 with the addition of molybdenum (18-8sMo) appeared, known today as 316 steel, followed by a modification with reduced carbon content – 316L steel. Reducing the carbon content from approx. 0.08% to a maximum of 0.03% reduces the tendency for chromium carbides to form at grain boundaries, which improves corrosion resistance in chloride-rich environments such as body fluids.

Chromium is primarily responsible for the corrosion resistance of stainless steels. Even with a Cr content of 11%, a thin protective oxide layer forms on the surface, giving the steel a so-called passive state. The addition of molybdenum increases resistance to pitting corrosion in chloride environments, making 316/316L steels more suitable for physiological conditions. Nickel, in turn, stabilises the austenitic phase (γ, fcc structure) at room temperature, making the material non-magnetic and improving its corrosion resistance.

Austenitic steels cannot be hardened by conventional heat treatment, but they respond very well to work hardening. This allows for a wide range of mechanical properties to be adjusted – from more ductile, soft structures to significantly hardened ones with high tensile strength. Mechanical data for 316L steel show that, depending on the degree of cold deformation, different combinations of strength and ductility can be achieved, which is important for matching the material to the specific function of the implant.

Despite their many advantages, 316 and 316L steels are not ideal materials. Under high stress conditions, especially in areas with limited oxygen access, such as around screw threads or bone plate connections, crevice and pitting corrosion may occur, and in the long term, fatigue corrosion may also occur. For this reason, stainless steels are most commonly used in temporary implants such as plates, screws, nails and fixation wires, which can be removed once the bone has healed. To improve their properties, surface modifications are widely used – from polishing and passivation in nitric acid to anodising or nitrogen implantation by glow discharge, which increases resistance to corrosion, wear and fatigue.

Cobalt and chromium alloys

When mechanical requirements exceed the capabilities of stainless steels, cobalt and chromium alloys come into play. There are two main groups of such alloys in biomaterials: cast CoCrMo alloy, used, among other things, in endoprosthesis cups and heads, and forged CoNiCrMo alloy, used in high-load components such as hip or knee prosthesis stems. ASTM standards describe several versions of such materials (F75, F90, F562, F563), but in clinical practice, CoCrMo and CoNiCrMo dominate.

Cobalt and chromium form a solid solution up to about 65% Co, and the addition of molybdenum causes grain refinement and, as a result, increased strength after casting or forging. Chromium plays a dual role: it increases corrosion resistance by forming a passive oxide layer and participates in solution strengthening. In clinical practice, Co–Cr alloys are characterised by a very high modulus of elasticity – in the range of 220–234 GPa, higher than stainless steels, and very good wear resistance.

However, this high stiffness has its consequences. An implant that is too stiff can take on too much of the load, leading to stress shielding – a reduction in the load on the patient’s own bone and its gradual resorption. Although the clinical significance of this effect is not entirely clear, it is an important factor in the design and shape of prosthetic stems. On the other hand, hardness and abrasion resistance make cobalt and chromium alloys an excellent choice for ‘metal-metal’ friction pairs, where minimising long-term wear is crucial. Studies of long-term endoprostheses with such pairs indicate a very low rate of linear wear, in the order of a few micrometres per year.

Another important issue is the release of ions from Co-Cr alloys and their potential toxicity. Experiments in Ringer’s solution have shown that the rate of nickel release from CoNiCrMo alloy and 316L steel is very similar after a certain period of time, even though the cobalt alloy contains about three times more nickel. In vitro studies have shown that cobalt particles can be toxic to bone-building cells, while chromium and Co-Cr alloy particles are much better tolerated. High concentrations of Co and Ni ion extracts clearly disrupt cell metabolism in cultures, while chromium ions show lower toxicity.

Titanium and its alloys

Among the metals used as biomaterials, titanium occupies a special position. In the electrochemical series, it is an ‘active’ element, but in a physiological environment it is covered with a very stable, passive oxide layer, thanks to which its corrosion current in physiological solutions is extremely low, on the order of 10⁻⁸ A/cm². In practice, titanium implants remain visually unchanged after a long period of time in the body.

Pure titanium (cp-Ti) and the most popular Ti–6Al–4V alloy combine very good corrosion resistance with a favourable strength-to-weight ratio. Their modulus of elasticity is lower than that of steel or Co–Cr alloys, which brings them closer to bone and potentially reduces the risk of stress shielding. On the other hand, titanium is not as rigid or as strong in tension as the best steels or cobalt alloys, so the design of load-bearing elements requires precise stress analysis and often a larger cross-section.

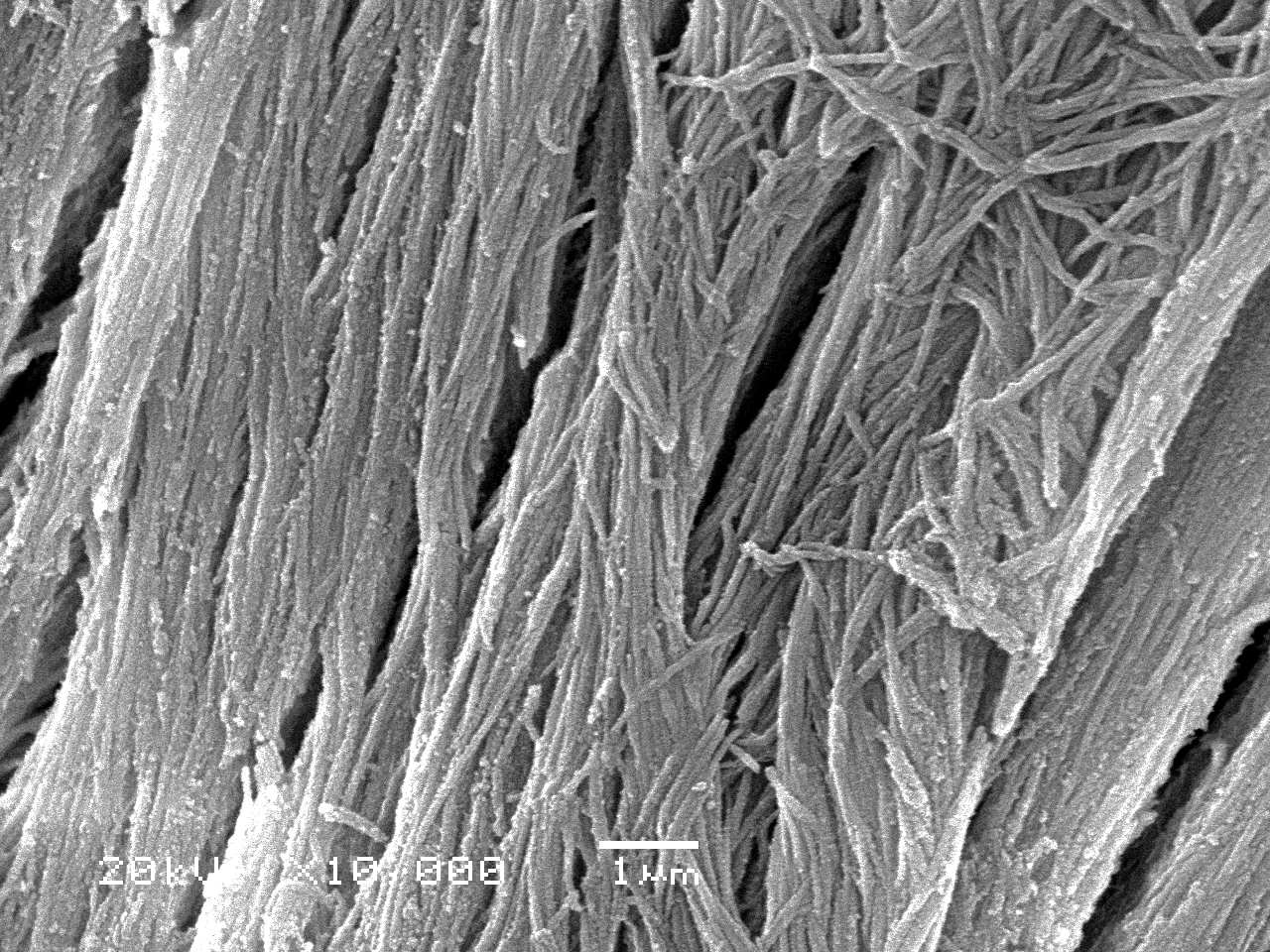

In recent decades, titanium alloys with reduced elastic modulus and increased corrosion resistance have also been developed, containing, among others, Nb and Zr, e.g. Ti–13Nb–13Zr, designed specifically for joint prostheses. In addition, surface hardening of Ti alloys (e.g. thermochemical treatment, nitriding) has been developed, which allows good biocompatibility of the substrate to be combined with high wear resistance in friction zones.

Nickel-titanium (NiTi) alloys, which exhibit shape memory and superelasticity, constitute a special group. Thanks to martensitic transformation, they can reproduce a previously recorded shape when heated above the transformation temperature or exhibit very high elastic deformability in a narrow stress range. This feature is used, among other things, in vascular stents, orthodontic arches and catheter guides, allowing for atraumatic insertion of devices and their stable expansion after dilation.

In the case of titanium, surface properties are particularly important. Studies show that both roughness and surface chemistry regulate the behaviour of osteoblasts and bone-forming cells – they affect adhesion, proliferation, and the production of growth factors and cytokines. Appropriate chemical treatment of the surface of Ti and its alloys can make them bioactive, i.e. capable of forming an apatite layer in contact with body fluids, which promotes direct bonding with bone.

Metals in dentistry and other special applications

Both precious metals and base metals are used in dentistry. Gold is practically corrosion-resistant (immunity-type resistance) and provides excellent durability and chemical stability in prosthetic reconstructions. However, its limitations are high density, insufficient strength for heavy loads and cost, which means that it is practically not used in orthopaedics.

Dental amalgam, an alloy of silver, tin, and mercury, is commonly used. Although the individual phases of this material are passive at neutral pH, in practice, amalgam often corrodes, especially in the presence of aeration differences under the bacterial plaque and local galvanic microcells. It is, in fact, the most corrosion-prone material used in dentistry, which manifests itself in discolouration and the formation of corrosion products on the surface of fillings.

The group of special metals also includes platinum metals and their alloys, used where chemical resistance and conductivity control are crucial, as well as Ni-Cu alloys and other systems used in hyperthermia – the deliberate heating of cancerous tissues using an induced magnetic field. These types of alloys are designed so that their thermal response in an electromagnetic field is well controlled, enabling precise delivery of heat energy to the tumour.

Corrosion of metallic implants in a biological environment

Corrosion is a central phenomenon for metallic biomaterials. In the body, we are dealing with an electrolyte fluid containing ions (Na⁺, Cl⁻, HCO₃⁻, phosphates), variable pH and potential differences between different areas – all these factors favour electrochemical reactions.

Pourbaix diagrams, which show the relationship between electrochemical potential and pH, are used to describe the stability of metals. They distinguish between areas of corrosion (activity), passivity and immunity. In the human body, different fluids have different pH and oxygenation levels: tissue fluid usually has a pH of around 7.4, but in the vicinity of a wound it can drop to as low as 3.5, and in an infected wound it can rise to 9.0. This means that a metal that performs well in one area of the body may corrode in another.

However, Pourbaix diagrams have limitations – they are based on equilibrium states in a simple metal-water-reaction products system. The presence of chloride ions or complex organic molecules can significantly alter the behaviour of the metal, and the predicted passivity may in practice prove to be overly optimistic. Therefore, polarisation curves are used in addition to these diagrams, which allow the corrosion current to be determined and, on this basis, the number of ions released into the tissues and the rate of material loss to be calculated. Alternatively, the loss of sample mass during exposure in a solution similar to body fluid is measured.

Corrosion of implant materials can take various forms. Uniform corrosion leads to relatively homogeneous material loss, but localised forms are much more dangerous. Pitting corrosion causes deep, localised losses – stainless steels are particularly susceptible to this in the presence of chlorides. Crevice corrosion occurs in areas with limited oxygen access, such as the gaps between the screw and the plate, where local chemical conditions (pH, ion concentration) differ significantly from the surrounding environment. Fretting is corrosion associated with micro-movements of two contacting surfaces – mechanical abrasion destroys the passive layer, exposing fresh metal and accelerating corrosion.

Stress corrosion and fatigue corrosion are special forms of corrosion. In the presence of mechanical stresses, especially repetitive ones, the rate of corrosion may increase and microcracks may propagate more rapidly. In stainless steel implants, for example, fractures of hip nails and pins have been observed where bending loads and an aggressive physiological environment were simultaneously present. In such cases, it is difficult to speak of ‘pure’ corrosion – it is always a dynamic interaction of chemistry, mechanics and microstructure.

Different metals behave differently in this respect. Precious metals, such as gold, are virtually corrosion-resistant – their standard electrochemical potential is positive, and in Pourbaix diagrams they occupy the immunity area. Titanium and Co–Cr alloys are based on passivity – they form a well-adhering, tight oxide layer, thanks to which their corrosion currents are very low and the surface remains stable. Stainless steels also benefit from the passivity of chromium, but their passive layer is less stable, making them more susceptible to pitting and crevice corrosion. Dental amalgam, on the other hand, although thermodynamically partially passive, is in practice a material highly susceptible to corrosion, especially in the presence of biofilm.

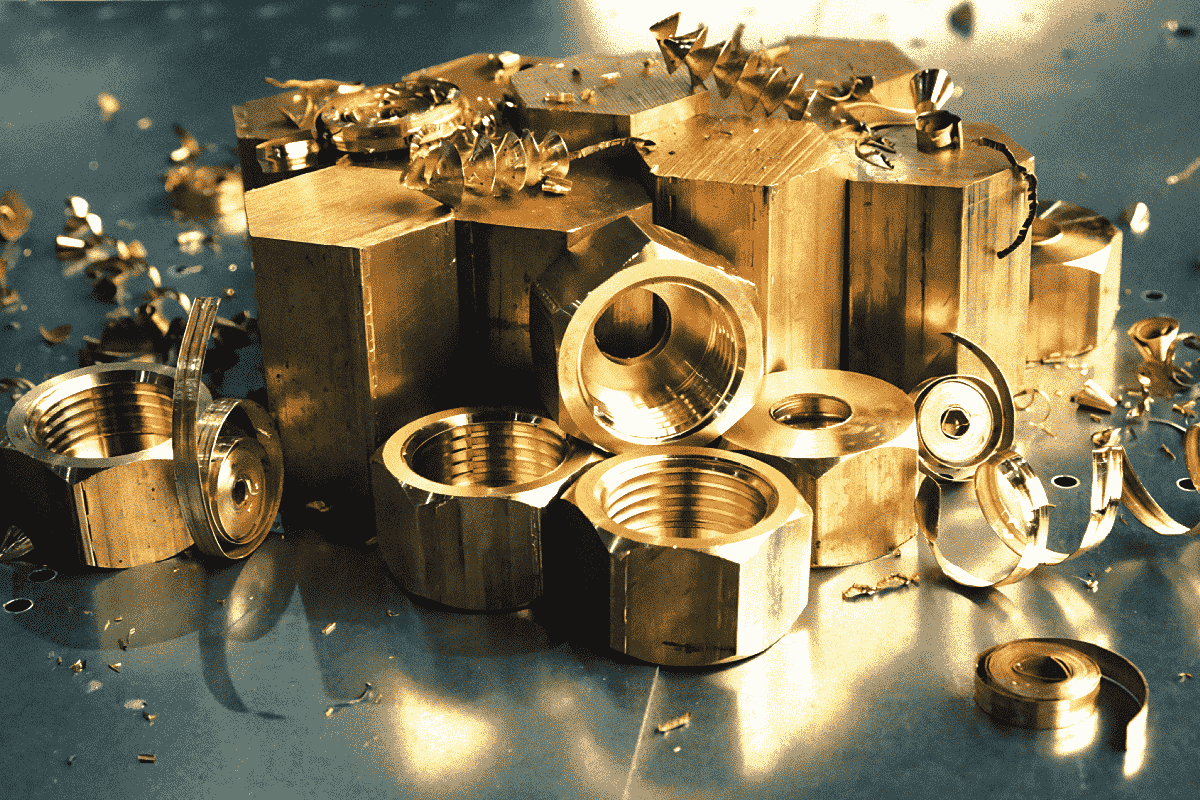

Manufacture and processing of metal implants

The manufacture of metal implants is not only a matter of shaping the geometry, but also of controlling the microstructure and surface condition, which determine fatigue strength, corrosion resistance and biological response.

In the case of stainless steels, it is crucial that austenitic steels harden very quickly under compression. This means that during cold working (rolling, drawing, bending), their strength increases, but at the same time their plasticity decreases. In order to restore the required level of deformability, intermediate annealing is used, whereby temperatures and times conducive to the precipitation of chromium carbides at the grain boundaries, which weaken corrosion resistance, must be avoided. After shaping, the components are cleaned, deoxidised (chemically or abrasively), and passivated, usually in a nitric acid solution in accordance with ASTM F86.

Co–Cr alloys behave differently – they are highly susceptible to strengthening during deformation, which in many cases makes conventional forging difficult. Therefore, components with complex geometries, such as prosthetic heads and cups, are often manufactured using precision casting (the so-called lost wax method). The process involves preparing a precise wax pattern, covering it with refractory material, burning out the wax and pouring liquid Co-CrMo alloy into the mould at high temperature. The mould temperature and cooling time affect the grain size and the size and distribution of carbides – a fine microstructure increases strength but can reduce resistance to brittle fracture, while larger grains and carbides improve ductility at the expense of strength. The designer must therefore find a compromise between strength and fracture resistance.

For titanium alloys, casting, forging and heat treatment processes, as well as surface treatment, are crucial. Titanium requires a protective atmosphere during high-temperature processing because it readily reacts with oxygen and nitrogen to form brittle surface layers. After initial mechanical processing, the surfaces of titanium implants are sandblasted, acid-etched, anodised or a combination of these processes, which results in favourable micrometre roughness and a modified oxide layer. Studies indicate that surfaces prepared in this way promote faster bone ingrowth and the formation of a strong mechanical and, potentially, chemical bond.

The processes of manufacturing shape memory alloys constitute a separate category. In their case, precise control of the chemical composition and heat treatment, which determine the martensitic transformation temperatures and the range of superelasticity, is crucial. NiTi stents or orthodontic arches must achieve the desired deformation and return to shape within a strictly defined temperature range, including physiological conditions.

Summary – Metallic biomaterials

Metallic biomaterials form an extensive family, in which each material occupies its own, fairly precisely defined functional niche. Stainless steels, especially type 316L, are relatively inexpensive and easy to process materials with good mechanical properties and sufficient corrosion resistance, which is why they are used primarily in temporary implants and less critical components. Co-Cr alloys offer very high strength, hardness and wear resistance, making them the material of choice for prosthetic cups and heads, as well as for stems, where durability under heavy loads is important. Titanium and its alloys, combining very good corrosion resistance, favourable elastic modulus, and high biocompatibility, have become the ‘gold standard’ for long-term implants, especially in orthopaedics and dental implantology.

Special alloys, such as shape memory NiTi, also play an important role, enabling completely new therapeutic strategies – from self-expanding stents to super-elastic orthodontic arches. Gold and amalgams remain important in dentistry, although their applications are being revised in light of aesthetic and safety requirements.

The common denominator for all metallic biomaterials is the need to control corrosion and tissue interaction. Pourbaix diagrams, polarisation curves, fatigue tests, and ion toxicity studies form the basis for the engineering design of these materials. Surface engineering is equally important – it determines the quality of the passive layer, wear resistance, cell adhesion, and the nature of the bond with the bone.

As a result, modern biomaterials engineering does not look at metals in isolation, but treats them as part of complex systems: a metal core can be coated with bioactive ceramics, surrounded by a polymer composite, or work with porous ceramic structures that support regeneration. Metals provide load-bearing capacity and plasticity, ceramics provide bioactivity and abrasion resistance, and polymers provide flexibility and the ability to form soft structures. Together, they form the foundation of modern implantology, where the goal is no longer just to ‘replace parts,’ but to achieve functional, biologically integrated organ reconstruction.