Steels and alloys with special properties

Table of contents

Steels and alloys with special properties are designed when the durability of a component is no longer determined solely by classic mechanical parameters, and one dominant function comes to the fore: wear resistance, corrosion resistance, stability at high temperatures, or deliberately shaped physical characteristics, such as high electrical resistance, specific thermal expansion, or magnetic properties. In such materials, the chemical composition and processing are not selected ‘generally’, but directly for the mechanism that is to operate during use: the material is to harden itself in the surface layer, passivate in a given environment, or form a protective scale in hot gases.

In practice, there is very rarely an alloy that is ‘resistant to everything’. Corrosion resistance is strongly dependent on the type of environment, abrasion resistance depends on whether ‘grinding’, friction, or wear under high pressure and impact predominates, and high-temperature properties must be considered separately as heat resistance (oxidation resistance) and heat resistance (resistance to creep). Therefore, a meaningful description of special steels is based on understanding ‘what produces the effect’ and ‘what the boundary conditions are’, rather than memorising a few names.

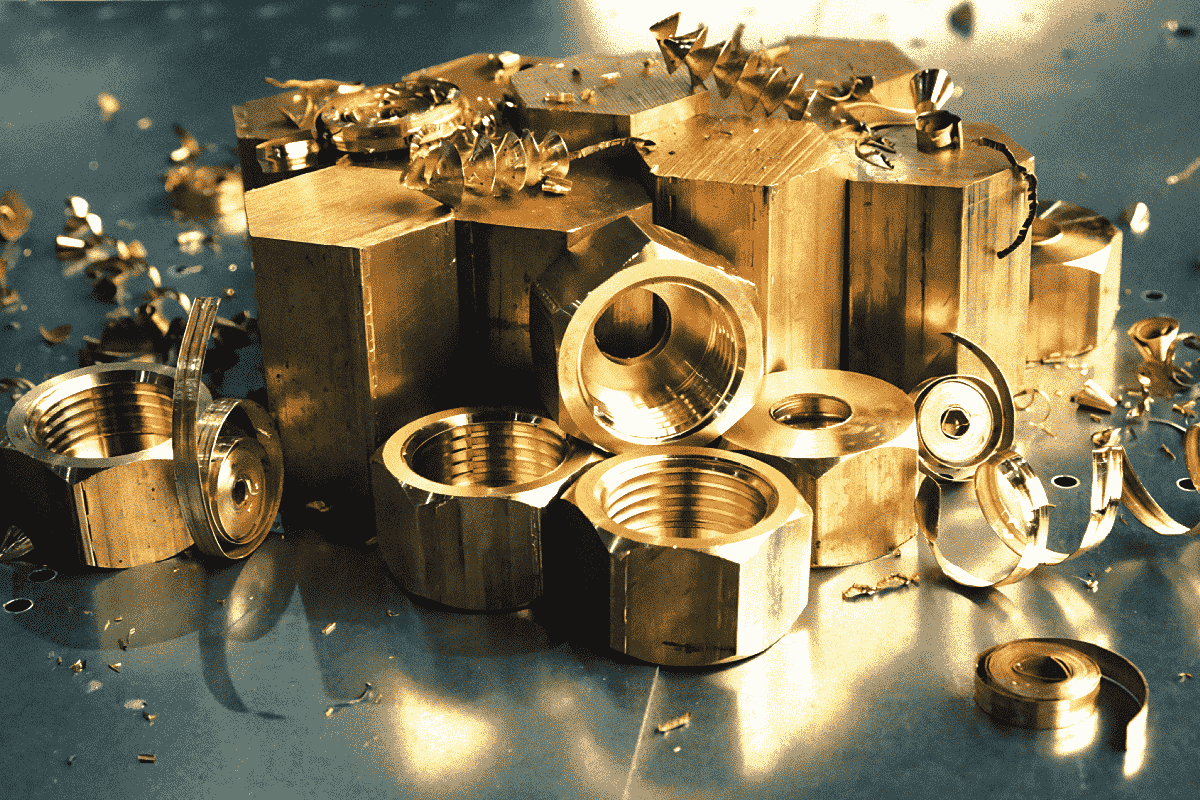

Abrasion-resistant steels

A very characteristic material with high abrasion resistance is austenitic manganese steel 11G12, containing approximately 1–1.3% C and 11–14% Mn, with a recommended carbon to manganese ratio close to 1:10, because only a sufficient carbon content ensures the durability of the austenitic structure. This steel, known as Hadfield steel, is distinguished by an unusual set of properties: it has a low yield strength (of the order of Re ≈ 400 MPa) and low hardness (approximately 210 HB), while at the same time having very high tensile strength (approximately Rm ≈ 1050 MPa) and exceptionally good plastic properties and impact strength (including A ≈ 50% and high Charpy impact strength).

The source of its wear resistance is not its ‘initial hardness’ but its behaviour under load. Because the steel has a low yield strength, it easily and very strongly work hardens, significantly more intensively than many typical structural steels. In addition, under pressure, the austenite in the surface layer can transform into martensite, which locally increases hardness and hinders further wear. This mechanism makes Hadfield steel resistant to both abrasion and impact, while classic hardened steels, although resistant to abrasion, often lose out in impact applications due to their brittleness.

A homogeneous austenitic structure is a prerequisite for obtaining the desired properties. When cooled slowly, carbide precipitates appear alongside austenite, which deteriorates the properties. Therefore, 11G12 steel is supersaturated at around 950–1000°C with water cooling to obtain the most homogeneous austenite possible. From a practical point of view, the limit of applicability is also important: Hadfield steel is resistant to abrasion primarily when wear is accompanied by significant surface pressure; under ‘grinding’ conditions without pressure, it does not show its advantage. For this reason, it is used for railway turnout crossings, breaker jaws, and vehicle tracks, i.e., where high-pressure and frequent impact loads occur simultaneously. The price for these advantages is very difficult machinability – in practice, mainly permissible with carbide tools.

Stainless, acid-resistant, and rust-resistant steels

Corrosion is the process of metal destruction caused by the external environment, starting on the surface and progressing inwards, with this progress sometimes being uneven. In terms of mechanism, a distinction is made between chemical corrosion, typical of the action of dry gases at high temperatures, and electrochemical corrosion, which occurs in liquids (most often in aqueous solutions) with the participation of electrolyte and current flow in local cells. The key observation is that the process can be inhibited if a layer of corrosion products forms on the surface that meets the conditions of a ‘protective barrier’: it must tightly cover the metal, not dissolve in the environment, adhere well, and have an expansion coefficient similar to that of the metal so that it does not crack during temperature changes. This intuitively leads to the idea of stainless steels, whose resistance results from maintaining a stable, tight passive layer.

In stainless steels, the most important component is chromium, because only a sufficiently high Cr content allows for permanent passivation. The material distinguishes, among others, chromium steels with different carbon contents and shows how the composition affects the structure in the Fe–Cr–C system. At very low carbon contents (below about 0.1%), the ferrite field can extend across the entire temperature range, and the steel has a ferritic structure; at medium carbon (approximately 0.20–0.30%), partial austenite appears after heating, and after cooling, a mixture of ferrite and martensite is obtained, resulting in semi-ferritic steels; at higher carbon, the steel completely transforms into austenite after heating and becomes martensitic after cooling. Against this background, examples of typical chromium steels are given: 0H13 as ferritic, 1H13 as semi-ferritic, and 2H13–4H13 as martensitic, with heat treatment consisting of hardening at 950–1000°C and tempering at 600–700°C, which allows a wide range of strengths to be obtained depending on the carbon content. These steels are resistant to corrosion in water vapour and in some acids (e.g., nitric or acetic), but are not resistant to hydrochloric and sulphuric acids, which clearly shows that ‘stainlessness’ is not absolute, but environmental.

In practice, there are also chromium stainless steels with a higher Cr content, for example grades in the range of 16–18% Cr and approximately 0.1% C (e.g. H17), often with a ferritic or ferritic-martensitic structure, used in the food industry or for everyday products, as well as steels with 25-28% Cr (e.g. H25T) with a ferritic structure, less ductile, but also useful as heat-resistant materials at higher temperatures. A significant limitation of ferritic steels is that they do not undergo allotropic transformation, so they cannot be ‘improved’ by classic heat treatment – grain refinement is mainly achieved by plastic working.

The highest corrosion resistance in many applications is achieved by austenitic chromium-nickel steels. Modern grades typically contain 18-25% Cr and 8-20% Ni, and the most common is 18/8 steel (and its variants), which is resistant to many corrosive media. Alloying additions allow the resistance to be ‘fine-tuned’: molybdenum (approximately 1.5-2.5%) increases resistance in sulphuric acid environments, copper (approximately 3%) reduces susceptibility to stress corrosion, and silicon (approximately 2–3%) can improve resistance to hydrochloric acid. To ensure a homogeneous austenitic structure, these steels are subjected to saturation at 1050–1100°C with water cooling, which is one of the key elements of stainless steel technology.

At the same time, austenitic chromium-nickel steels have a typical ‘operational trap’: a tendency to intergranular corrosion after exposure to temperatures in the range of approximately 450–700°C, when chromium carbides can be released at the grain boundaries, depleting the boundaries of chromium and locally removing passivation. The material indicates classic ways of limiting this phenomenon: very low carbon content (in the range of 0.02–0.03%), stabilisation with strongly carbide-forming elements (titanium, niobium), stabilising annealing at around 850°C, and supersaturation. This is a good example of how, in special steels, the result is determined not only by the composition, but also by the ‘thermal history’ of the material.

On the borderline between classic stainless steels are steels that are difficult to rust, used mainly for atmospheric corrosion. The idea behind them is that over time, the surface becomes covered with a layer of compact, low-permeability rust that adheres well to the substrate and slows down further corrosion; this protective rust is called patina. Copper (approximately 0.20-0.50%) plays an important role in this group, and to make the protective effect more pronounced, chromium (up to approximately 1.3%) and nickel are also used, while phosphorus in the presence of these components further increases resistance, which is why its content is sometimes increased. The well-known ‘Cor-ten A’ steel and its equivalent (10HNAP) are given as examples, which clearly show that sometimes the goal is not complete stainlessness, but rather to achieve stable protection in atmospheric conditions.

Heat resistance, heat durability, creep, and selection of material groups

Working at high temperatures poses two different requirements. Heat resistance means resistance to the oxidising effect of gases at temperatures above 550°C, i.e., in the red-hot range, where carbon steel quickly forms scale, and the rate of oxidation increases rapidly with temperature. Heat resistance is increased by additives such as chromium, silicon, and aluminium, which, having a greater affinity for oxygen than iron, form a compact, tightly adhering layer of oxides that inhibits further oxidation. The material provides a very practical relationship: with a content of above 10% Cr, steel can be heat-resistant at around 900°C, while ensuring heat resistance at 1100°C usually requires 20-25% Cr. It is also crucial that heat-resistant steel does not undergo allotropic transformations within the operating temperature range, as the associated volume changes can compromise the integrity of the protective layer.

The second requirement is heat resistance, i.e., the ability to withstand long-term loads at high temperatures without excessive deformation. This is where the phenomenon of creep comes into play: under constant stress, the material elongates over time, and a typical creep curve includes a section where the rate of deformation is approximately constant; it is this section that is particularly important when comparing materials. Creep can be understood as a ‘struggle’ between two processes: strengthening through the increase in dislocation density and high-temperature recovery, which removes this strengthening. In heat-resistant materials, the aim is therefore to ensure that the structure resists recovery and recrystallisation as effectively as possible at operating temperatures.

In heat-resistant steels, additions of molybdenum, tungsten, and vanadium are important, but they do not provide oxidation resistance on their own, which is why in practice, heat-resistant steels combine them with additives that increase heat resistance, primarily chromium, but also silicon and aluminium. If an austenitic structure is required, nickel and manganese are also used. The material also indicates the standard approach to heat resistance characteristics (in the context of creep) through time values: the stress causing a specific permanent deformation after a given time at a given temperature and the stress causing rupture after a given time at a given temperature, which emphasises that ‘high-temperature strength’ is always related to the exposure time.

The choice of material at high temperatures is highly dependent on the working range. The material shows a practical division: in the range of approximately 350–500°C, ferritic or ferritic-pearlitic alloy steels are used; in the range of 500–650°C, austenitic steels are more common; in the range of 650–900°C, nickel and cobalt-based alloys are used; and above 900°C – alloys of refractory metals (including molybdenum and chromium). This division explains well why Cr-Mo steels with moderate additives are typical for boilers and power installations, while turbines and jet engines require alloys with a completely different ‘class’ of structural stability.

In the group of heat-resistant ferritic and ferritic-pearlitic steels, intended for long-term operation usually up to about 500–550°C, the material gives examples of boiler tube steels containing approximately 0.1–0.2% C, about 1–2% Cr, and 0.5–1% Mo. They are weldable but require preheating before welding, and after welding, the joint is normalised and tempered (the material specifies tempering at approximately 700°C) in order to obtain the most stable structure possible. This shows that in high-temperature steels, the joint fabrication technology is part of the ‘material package’ and not an add-on at the end.

Heat-resistant steels include chromium-aluminium, chromium-silicon, and chromium-nickel steels, and in applications such as engine valves, steels with increased chromium and silicon content are used, for example, so-called silchroms containing approximately 0.4–0.5% C, 8–10% Cr, and 2–3% Si. Their heat treatment includes hardening at around 1050°C and tempering at 680–700°C, which combines the heat resistance of the component (chromium/silicon) with the strength requirements of the element.

For the most demanding conditions, especially in turbines and jet engines, the material is described by special groups of heat-resistant alloys: austenitic iron-based alloys with chromium and nickel, complex Cr-Ni-Co-Fe alloys, cobalt-based alloys, and nickel-based alloys (nimonic). Typical operating temperature ranges and characteristic heat treatments are indicated, for example, supersaturation and ageing (for Cr-Ni-Co-Fe alloys, supersaturation in a very high temperature range and ageing at around several hundred degrees; for Nimonic alloys, supersaturation in the range of approximately 1050–1200°C and ageing at approximately 700°C). This is a different philosophy than in structural steels: here, the properties result largely from creep resistance and controlled precipitation hardening at high temperatures, and not just from ‘hardening and tempering’.

Special physical properties

In electric heating and resistance elements, materials with high specific resistance, low resistance increase at high temperatures, and at the same time high heat resistance, low thermal expansion, and high melting point are required. The material emphasises that a solid solution structure is advantageous here, as this type of structure promotes greater electrical resistance than phase mixtures. In practice, two main families of materials are used: nickel-chromium alloys (nichromes) or austenitic chromium-nickel steels with a composition similar to heat-resistant steels, as well as ferritic chromium-aluminium steels known under trade names (e.g. Kanthal, Alchrom).

A separate group consists of alloys designed for a specific thermal expansion coefficient. The material shows a particularly strong dependence of expansion on the composition of Fe-Ni alloys. A classic example is invar, containing about 36% Ni, which has very low expansion in the range of approximately –80 to +150°C, with the coefficient increasing significantly outside this range. Even lower expansion in a certain temperature range is achieved by superinvar, containing approximately 30–32% Ni, 4–6% Co, and very little carbon. These alloys are used in instruments and mechanisms that should not change their dimensions with temperature fluctuations, as well as in gas condensation devices.

The second family of Fe-Ni alloys is selected so that the expansion matches that of glass. An example is platinumite with a content of approximately 46% Ni and low carbon, used for melting into glass in light bulbs and electron tubes. In the same area of application, there are also bimetals, i.e., two-layer strips obtained by welding materials with different expansion coefficients. When such an element heats up, the difference in expansion causes it to bend, which is used in temperature measurement and control devices, switches, relays, and thermal protection devices.

Magnetic properties – soft, hard, and non-magnetic materials

In electrical engineering, materials are divided into magnetically soft, magnetically hard, and non-magnetic, and the requirements for each group are different. Magnetically soft materials are easy to magnetise and demagnetise, so their structure should be coarse-grained and as close to equilibrium as possible, and the content of carbon and harmful impurities (sulphur, phosphorus, oxygen, nitrogen) should be as low as possible, as they increase coercivity and losses. The simplest example is technically pure iron used for electromagnets and relay cores, but low-carbon steels are also commonly used. In practice, silicon steels, in which silicon is present in a solid solution, are also very important; these are the basic materials for electrical steel sheets.

The material also points out that Fe-Ni alloys can exhibit particularly good magnetic properties, and permalloy (an Fe-Ni alloy with a high nickel content) is often cited as an example of a classic alloy with very high magnetic permeability, which corresponds well with the practice of using nickel alloys in precision equipment. In the field of permanent magnets, i.e., magnetically hard materials, the aim is for the material to retain its magnetisation after magnetisation, which requires different structural characteristics and often different alloying additives. The material emphasises that the best magnetic properties (in the context of magnets) are exhibited by steels containing cobalt, although their use is limited by the availability of cobalt.

A very important family of alloy magnets are Fe-Ni-Al-Co alloys, known as alniko, typically containing 14-28% Ni, 6-12% Al and 5–35% Co. Their properties are obtained not only through their composition, but also through heat treatment involving homogenisation at high temperature, followed by supersaturation (in water or oil) and then ageing in a medium temperature range. This allows alnico to be used to make strong magnets with small dimensions and low weight, which is crucial in many devices.

In some applications, however, non-magnetic materials are needed, which behave neutrally in a magnetic field. The material indicated here is chromium-nickel-manganese steel (e.g., H12N11G6) and chromium-manganese steel (e.g., G18H3), which are heat-treated by supersaturation, and whose mechanical properties can be further improved by cold deformation. This shows that in the ‘magnetic’ group, special steel can be designed both to maximise and to minimise magnetic phenomena.

Steels and alloys with special properties – summary

Steels and alloys with special properties are materials designed for the dominant working mechanism rather than for ‘average’ strength. In wear-resistant steels, such as Hadfield steel, self-hardening under load and the possibility of surface transformation are key, which provides wear resistance while maintaining impact strength, but at the same time introduces operational and technological limitations (pressure, machinability). In stainless and acid-resistant steels, the basis is passivation based mainly on chromium, while the actual durability depends on the structure, alloying additives, and thermal history, an example of which is the problem of intergranular corrosion in austenitic steels after heating to certain temperatures. In high-temperature applications, the requirements for heat resistance and heat resistance must be separated, understanding the role of protective scale and creep, and the choice of materials ranges from Cr-Mo steels to nickel and cobalt-based superalloys as the operating temperature increases. Finally, physical properties such as electrical resistance, thermal expansion, and magnetism show that steel and alloys can be designed as functional components of a device – from resistance wire and thermal bimetal to permanent magnets made of aluminium and non-magnetic steel for use in magnetic fields.