Alloying elements in iron-carbon alloys

Table of contents

Carbon steel can achieve a very wide range of properties through heat treatment, but in many applications this is still not enough. The introduction of components other than iron and carbon into steel (or an increase in the content of certain additives, such as manganese and silicon) creates a group of materials called alloy steels. These deliberately added elements – alloying additives – interact simultaneously with iron, carbon and each other, resulting in a change in structure and properties. This makes it possible to achieve higher mechanical and technological properties, increased hardenability, high hardness and abrasion resistance, as well as special properties (e.g. corrosion resistance, heat resistance or heat resistance).

At the same time, alloy steel is generally more expensive, so it is used when carbon steel does not meet the requirements. In practice, it is also important that alloy steels are most often used in a heat-treated state, because only then do the effects of alloying fully manifest themselves: changed kinetics of austenite transformation, different tendency to grain growth, the possibility of producing and stabilising alloy carbides, and obtaining favourable combinations of hardness and plasticity.

How are alloy steels classified and why is this classification sometimes ambiguous?

The classification of alloy steels can be based on several criteria, but the most common classification is according to the type and amount of alloying additives, i.e. according to chemical composition. Hence the names such as chromium steels, manganese steels, chromium-nickel steels. However, the material points out that with today’s increasingly complex chemical compositions, this classification is less clear-cut, as steel may contain several important additives at the same time, and its behaviour depends on their combination, not just on the ‘main’ element.

From the point of view of technology and material selection, the classification according to the amount of alloying additives into low-alloy, medium-alloy and high-alloy steels is equally important, and with very low contents, we refer to micro-alloy steels. The classification according to application is also of great practical importance: we distinguish between structural steels, tool steels and steels with special properties. There is a simple logic behind this classification: different applications require different ‘mechanisms’ of strengthening (e.g. carbide precipitation, increased hardenability, structure stabilisation at high temperatures), and therefore different additives.

Marking of alloy steels

The material describes a marking system in which the steel mark consists of numbers and letters, and their meaning is closely related to the composition. The first number usually indicates the average carbon content in hundredths of a percent, while the numbers after the letters indicate the average content of a given alloying element in percent. If there is no number after the letter, it means that the content of the element does not exceed 1.5%. In addition, higher quality steels with very low phosphorus and sulphur content are marked with the letter A at the end of the mark.

It is also important to note that in the system cited, the letters originate from the Russian alphabet and correspond to specific elements (e.g. the letter for nickel, chromium or molybdenum in this system is different from that in modern chemical symbols). The material also provides an example of how to interpret the marking, showing how to read the carbon and main additive content ranges from the mark itself and how to recognise whether the steel is of ordinary or higher quality.

In tool steels, the marking system is different: at the beginning, there are letters indicating the functional group (e.g. steels for cold working, hot working and high-speed steels), and the following letters and numbers are used to indicate the main alloying additives or their groups and to distinguish between grades. The material also provides a list of letters assigned to elements in tool markings (e.g. separate markings for tungsten, vanadium, molybdenum, chromium, cobalt, etc.).

Alloying elements and iron allotropy

One of the most important effects of alloying is the influence of additives on the stability range of iron allotropes, i.e. on the temperatures at which austenite (γ phase) can exist. The material divides the elements into two basic groups according to how they shift the A3 and A4 transition temperatures. The elements of the first group lower A3 and raise A4, which means that the range of existence of the γ phase expands. With a sufficiently high content, a situation may arise in which the γ phase exists from ambient temperature to melting temperature – this is a system with an open austenite field. This effect has been described for iron alloys with nickel, cobalt and manganese, which form continuous solid solutions with iron.

If the elements expanding the γ field do not form continuous solutions, but only boundary solutions, the picture is more complex: the γ field may initially expand, but later – as a result of the appearance of two-phase ranges – gradually narrow until it even disappears. The material refers to this case as a system with an expanded austenite field and gives examples (including certain systems with copper or gold, as well as the influence of interstitial elements such as carbon and nitrogen).

The second group has the opposite effect: these elements lower A4 and raise A3, and with sufficient solubility in iron, they can lead to the formation of a closed austenite field, limited by the two-phase area α + γ. Outside this field, ferrite exists from normal temperatures up to the melting point. The material lists a wide range of elements that exhibit this effect (including aluminium, silicon, titanium, vanadium, chromium, molybdenum, tungsten and others). When the solubility in γ is too low, instead of a closed field, a system with a narrowed austenite field is formed, as described, for example, for alloys with boron, zirconium and caesium.

In what form do alloying additives occur in steel?

How an additive works depends largely on where and in what form it is found in the microstructure. The material lists various possibilities: alloying elements can occur in solid solution, as carbides, as non-metallic inclusions, as intermetallic compounds or (rarely) in free form. At the same time, it is emphasised that in practically used alloy steels, two forms are of key importance: solid solution and carbides, as they most strongly determine the properties and behaviour during heat treatment.

Non-metallic inclusions usually occur in small quantities, and their influence depends more on their shape, size and distribution than on their chemical composition. Intermetallic compounds can form, but most often only at very high additive contents, so in typical engineering steels they are less important than solid solution and carbides. This conclusion guides further analysis: if we want to understand why alloy steel is harder, more hardenable or more resistant to overheating, we usually need to look at solution hardening and the role of alloy carbides.

The effect of additives in the solid solution on ferrite

Many alloying elements dissolve in ferrite or austenite, but the degree of this solubility is individual and related, among other things, to the matching of atom sizes. The material refers to the criterion of atomic diameter difference and shows the range in which the formation of solid solutions is particularly favourable, and also reminds us of interstitial elements (such as carbon, nitrogen or boron) that form interstitial solutions in iron.

The most important engineering effect is as follows: additives dissolved in ferrite increase tensile strength, yield strength and hardness, while decreasing plastic properties. The material points out that the greater the difference between a given element and iron (e.g. in terms of atomic size), the greater the change. Qualitative information is also provided on which elements harden ferrite the most: manganese, silicon and nickel, among others, cause significant hardening, while the effect of chromium, molybdenum and tungsten is less pronounced. With regard to impact strength, it is indicated that most of these elements (with the exception of chromium and nickel) reduce it, and of the additives considered, nickel is the most beneficial because it can increase both hardness and impact strength.

It is also worth considering the dependence on the cooling rate. The material describes that ferrite containing nickel, chromium or manganese in solution can form a needle-like structure similar in appearance to martensite when cooled rapidly, resulting in an increase in hardness of 100-150 HB compared to the state after slow cooling. For ferrite with silicon, molybdenum or tungsten, however, this dependence on the cooling rate is negligible. This is an important observation because it shows that even ‘the same composition’ can result in different hardness if the cooling process is changed.

Alloy carbides

In alloy steels, not only the solid solution but also the carbides often play a key role. The material explains that the tendency of elements to form carbides is related to their electronic structure, and the practical conclusion is that elements can be ranked according to their increasing ability to form stable carbides: Fe, Mn, Cr, Mo, W, V, Ti, Zr, Nb. The more stable the carbide, the higher the temperature at which it dissolves in austenite during heating and the more difficult it is to separate from martensite during tempering, which directly affects the selection of austenitising and tempering temperatures in alloy steels.

The material also cites Goldschmidt’s classification, which organises carbide types according to crystal structure and properties. Group I carbides, with a regular NaCl-type lattice and MC formula (e.g. TiC, ZrC, VC, NbC), are very stable, have very high melting points and very high hardness. Group II includes carbides with a compact hexagonal lattice, of the MC or M2C type (e.g. WC, W2C, MoC), with slightly lower melting points and hardness. Group III consists of M3C carbides with a cementite structure (including Fe3C and Mn3C), with lower hardness compared to the most stable carbides of groups I and II.

At the same time, it was emphasised that alloy carbides rarely occur ‘in their pure form’. They usually contain iron in solution, and if the steel has several additives, the carbides may also contain these elements. Carbides with a similar structure can dissolve each other (e.g. cementite and manganese carbide), and steels also contain carbides with more complex patterns, such as M23C6 or M7C3. The material also highlights an important technological distinction: simple carbides such as MC and M2C are very stable and difficult to dissolve in austenite even at high temperatures, while complex carbides dissolve more easily when heated.

Carbide-forming and non-carbide-forming elements

The material proposes a convenient classification of alloying elements based on their interaction with carbon. The non-carbide-forming group includes, among others, Ni, Si, Co, Al, Cu and N. In steels, these elements generally occur in a solid solution in iron, with important exceptions: copper with a content above approximately 0.5% can form a separate phase (a solid solution on a copper matrix), and nitrogen can form compounds in the form of nitrides.

Carbide-forming elements are more ‘dual-track’: they can occur both in solid solution and as carbides, and which form dominates depends on the carbon content and what other carbide-forming elements are present. The material provides practical logic here: with a higher carbon content and a small amount of carbide-forming additives, these elements will mainly be in carbides, while with a low carbon content and a high content of carbide-forming additives, the carbon will be bound in carbides and the ‘excess’ additives will remain in the solid solution. Which elements will bind in carbides first is determined by their affinity for carbon.

At this point, the material clearly emphasises that the effect of carbides on properties is generally many times stronger than the hardening of ferrite by additives dissolved in the solution. Furthermore, the ‘power’ of carbides in practice is mainly determined by their dispersion and morphology: large carbide particles have a lower strengthening effect, plate-like precipitates impair plasticity more than spheroidal ones with the same hardness, and carbides at grain boundaries can cause brittleness.

How do alloying additives change the Fe-Fe₃C system?

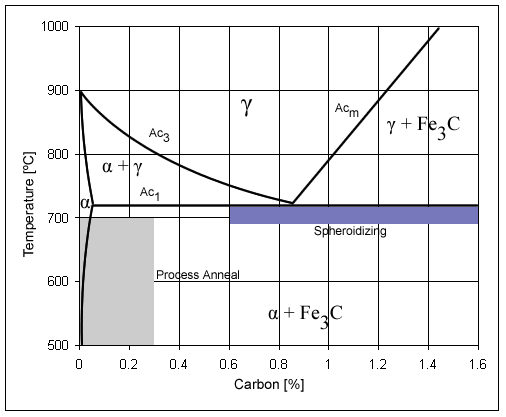

The introduction of alloying additives changes the position of characteristic temperatures and points in the iron-cementite system. The material states that elements that extend the range of the γ phase lower the Ac3 transformation temperature, while elements that narrow the γ field raise Ac3, which is particularly evident at low carbon content. A similar effect (to a certain extent) applies to the eutectoid transformation temperature, because there is also an allotropic transformation ‘in the background’.

The effect on the carbon concentration at the eutectoid point is also very important. The material states that all alloying elements shift the pearlite point S to the left, i.e. towards lower carbon contents, reducing the carbon content in the alloy pearlite. Similarly, most additives shift point E, which determines the solubility limit of carbon in austenite, to the left, with the strongest effect being exerted by (in ascending order of effect) W, Si, Cr, Mo, V, Ti. The shift of point E can be so large that even with a carbon content below 2% in alloy steels, a ledeburitic structure may appear, which is a strong signal that a simple Fe-Fe₃C diagram is no longer sufficient to predict the structure of alloy steels.

The material draws an unambiguous methodological conclusion from this: the more additives and the higher their content, the more the transformation temperatures and the position of characteristic points change, which is why for alloy steels one should not ‘mechanically’ use only the iron-cementite system, but remember the multi-component nature of equilibrium.

The influence of additives on CTPi graphs

The most ‘practical’ for heat treatment is how alloying additives change the transformations of supercooled austenite visible in CTPi graphs. The material explains that non-carbide-forming elements (e.g. Ni, Cu, Si, Al, Co) usually do not change the shape of the curves of the beginning and end of the austenite transformation, but shift them to the right, which means an increase in the stability of supercooled austenite and a slowdown in its transformations. At the same time, an exception is indicated: cobalt may act differently and accelerate the transformation.

In the case of carbide-forming elements, the picture is more complex, especially at higher carbon contents. The material states that these additives cause, in particular, a delay in pearlitic transformation, often also an increase in the maximum temperature of pearlitic transformation (with the exception of manganese), a lowering of the upper limit of bainitic transformation temperatures and a delay in bainitic transformation, but usually less than in pearlitic transformation. The result is a ‘spreading’ of the perlitic and bainitic transformation ranges, which can overlap in non-alloy steels. With increasing alloying additive content, two distinct transformation rate maxima may appear, separated by a range of high austenite stability.

However, it is very important to note that the effect of carbide-forming additives on the stability of austenite depends on how much of them is actually present in austenite, i.e. whether they have had time to dissolve during austenitisation. The material emphasises that carbide-forming elements increase the stability of supercooled austenite only if they have been completely dissolved in it during heating. If, on the other hand, they remain as undissolved carbides, the effect may be the opposite: austenite becomes poorer in additives and carbon, and the carbides themselves can act as nuclei, promoting accelerated transformation. This explains why the right temperature and austenitisation time are so important in alloy steels.

Alloying elements in iron-carbon alloys – summary

From an engineering perspective, alloying elements in Fe-C steels can be understood as a tool operating on three related levels. First, they modify the phase equilibrium, shifting the transformation temperatures and austenite stability, sometimes to the point of forming systems with an open, closed or narrowed γ field. Secondly, they influence the kinetics of transformations, shifting CTPi diagrams, increasing the stability of austenite, changing the pearlite-bainite relationship and shaping hardenability by lowering the critical cooling rate. Thirdly, they build properties through microstructure: they solution harden ferrite, but above all, through alloy carbides, they enable strong strengthening, grain growth control and special effects during tempering, including secondary hardness.

In practice, this means that alloying additives are not ‘bonuses to the composition’ but elements of a structure control system: their real effect depends on whether they are dissolved in austenite or occur as carbides, what their dispersion is, and how austenitisation, cooling and tempering proceed. Only a consistent view of these relationships allows the full potential of alloy steels to be exploited.