Gaspard Monge – Father of Descriptive Geometry

Table of contents

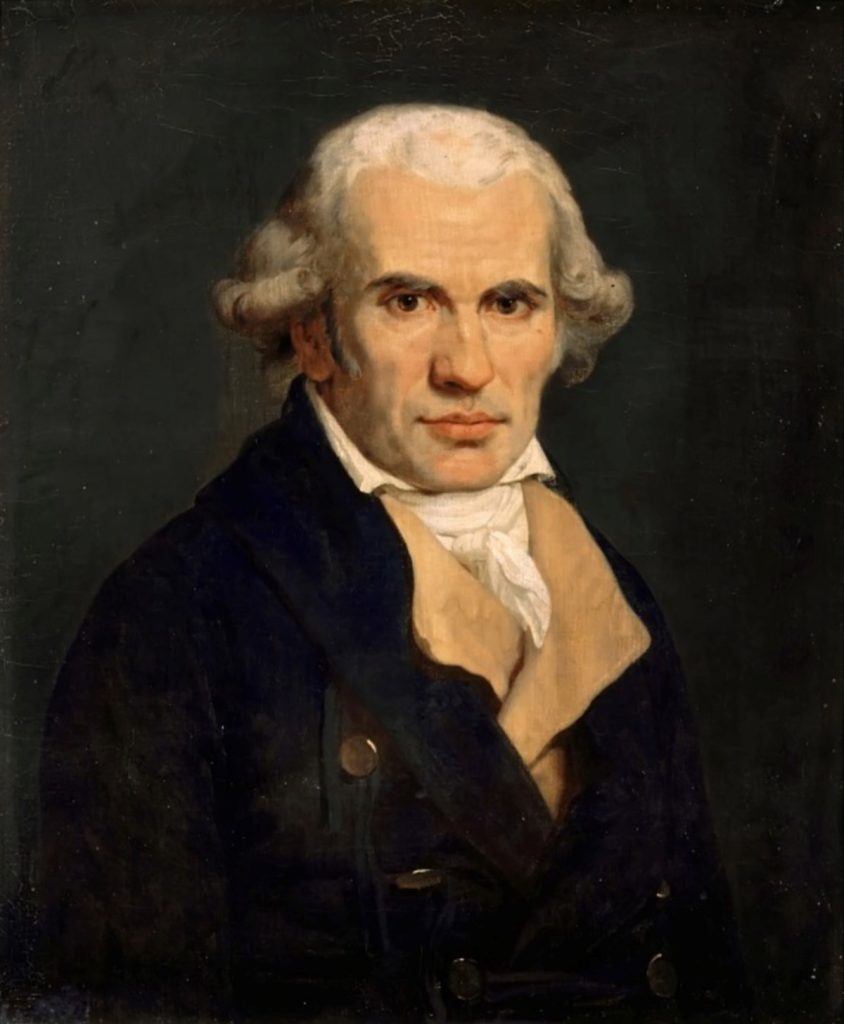

Gaspard Monge, born May 9, 1746, in Beaune, France, was one of the most influential mathematicians of the 18th century. He is recognized as the founder of descriptive geometry, a method that forever changed how we represent three-dimensional objects on a plane. His work in this field became the foundation of modern engineering and technical design, and its importance is still evident today in every branch of technical science. Thanks to its precisely defined principles, descriptive geometry is used in architecture, mechanics, and even art.

However, Monge’s contribution to science was not limited to geometry. He pioneered the study of surfaces and their curvatures, which contributed to the development of differential geometry – another key mathematical discipline. His work on the theory of differential equations and their applications in physics and engineering profoundly influenced subsequent generations of researchers. As one of his biographers notes: “Monge not only created new mathematical tools but also laid the foundation for a system of technical education that survives to this day.”

Monge also played an essential role in his era’s political and social life. His involvement in the French Revolution, his activities in the Ministry of the Navy, and his participation in founding the École Polytechnique – one of France’s most important technical universities – prove that he was a man with broad horizons and a deep sense of duty to society. This combination of mathematical genius and social commitment makes Monge a highly inspirational figure for scientists and engineers alike.

Childhood and youth

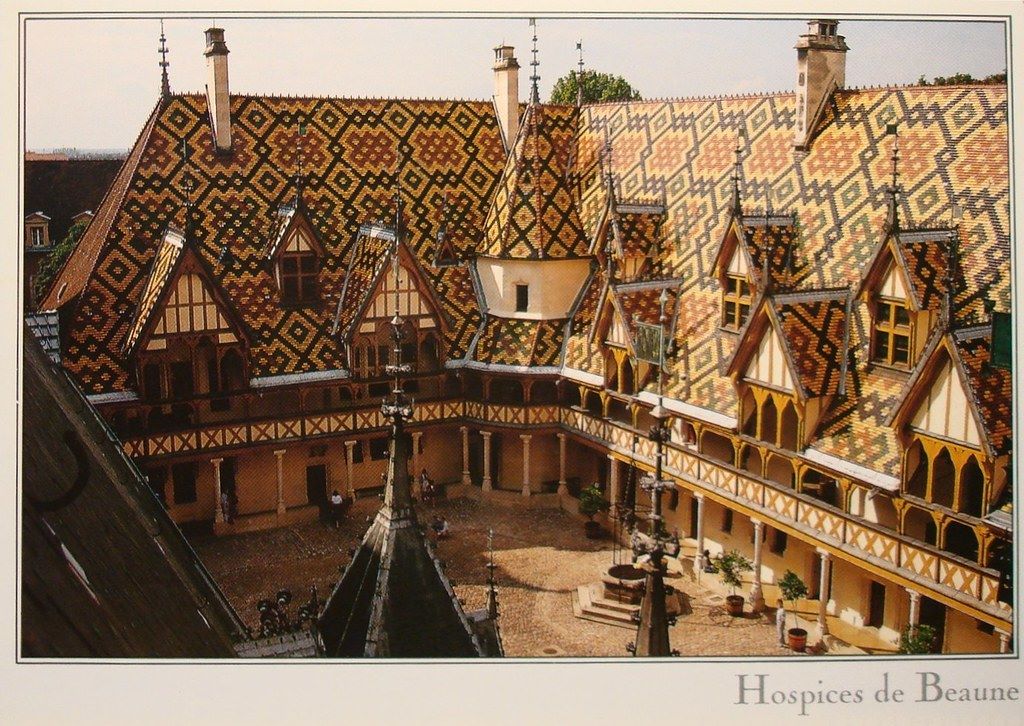

Gaspard Monge was born on May 9, 1746, in Beaune, a picturesque town located in the heart of Burgundy, a region known for its wine-making traditions. He was the son of Jacques Monge, a merchant initially from Haute-Savoie, and Jeanne Rousseaux, a representative of an old Burgundian family. Although not aristocratic, the Monge family led a comfortable life thanks to a growing trade, which allowed young Gaspard access to a good education. Even in his early years, he revealed a remarkable sharpness and curiosity about the world, which prompted his parents to provide him with a careful education.

Monge took his first steps in education at a school run by the Oratorian Order in Beaune. This institution, known for its high level of education, offered a broad program covering the humanities and natural sciences, which fostered Gaspard’s intellectual development. Mathematics was given a special place in the program, which quickly became his favorite subject. Even then, his teachers noticed his exceptional analytical skills and problem-solving talent.

At the age of 16, Monge moved to Lyon, where he continued his studies at the prestigious Collège de la Trinité. This school, run by the Jesuits, stood out for its innovative approach to education, emphasizing the sciences, as well as physics and chemistry. The young Monge quickly gained recognition for his achievements. Just a year after starting school, he was appointed as the school’s physics teacher, an unusual honor for a 17-year-old student. His teaching abilities and technical knowledge were several years ahead of his peers.

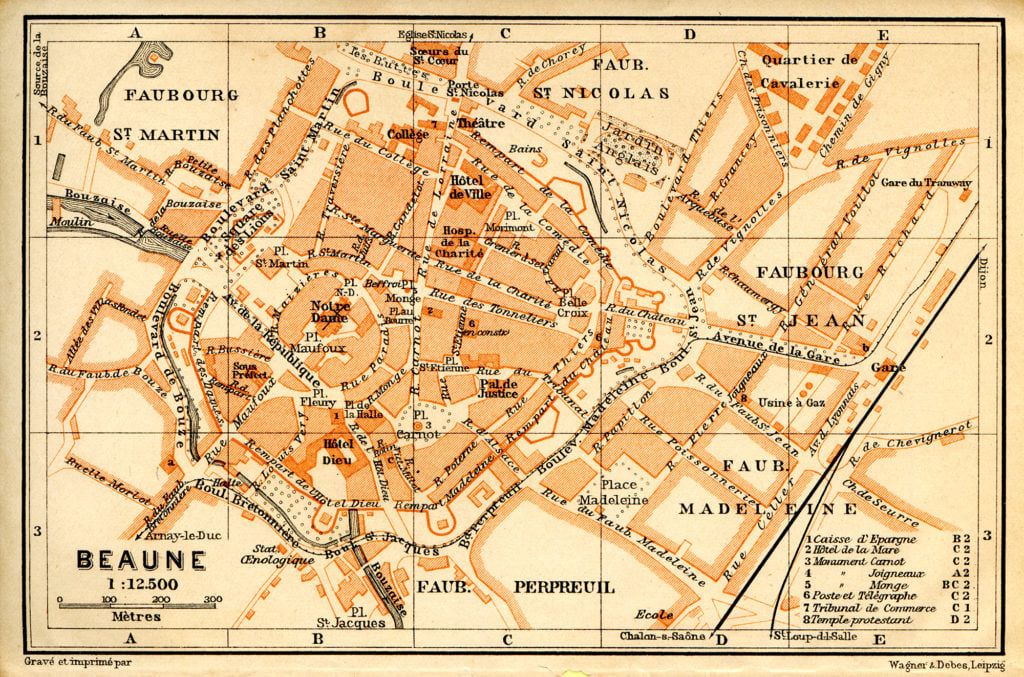

After completing his education in 1764, Monge returned to his native Beaune, where he undertook his first major project – making a detailed plan of the city. This work not only demonstrated his precision and technical talent but also revealed an innovative approach to observation and cartography. Beaune’s plan, in which he used instruments he had constructed himself, won the admiration of local authorities and military engineers. The document was later deposited in the city archives as a testament to his extraordinary abilities. As Monge himself later recalled: “This experience made me realize that science is a tool for changing the world.”

This work opened the door to his future career. In 1765, thanks to the recommendation of a military engineering officer, Monge was offered a job at the École Royale du Génie in Mézières, one of the most prestigious technical institutions of the time. Thus began his path to the heights of science and technology.

Scientific career and development of descriptive geometry

In 1765, Gaspard Monge took a position at the École Royale du Génie in Mézières and began working intensively as a draftsman, preparing plans and models for fortifications and military architecture. At first, his tasks were purely technical and did not require him to use his mathematical talent, which somewhat disappointed him. However, in his spare time, Monge developed his own ideas and experimented with new methods of representing spatial objects on a plane to revolutionize engineering and technical design.

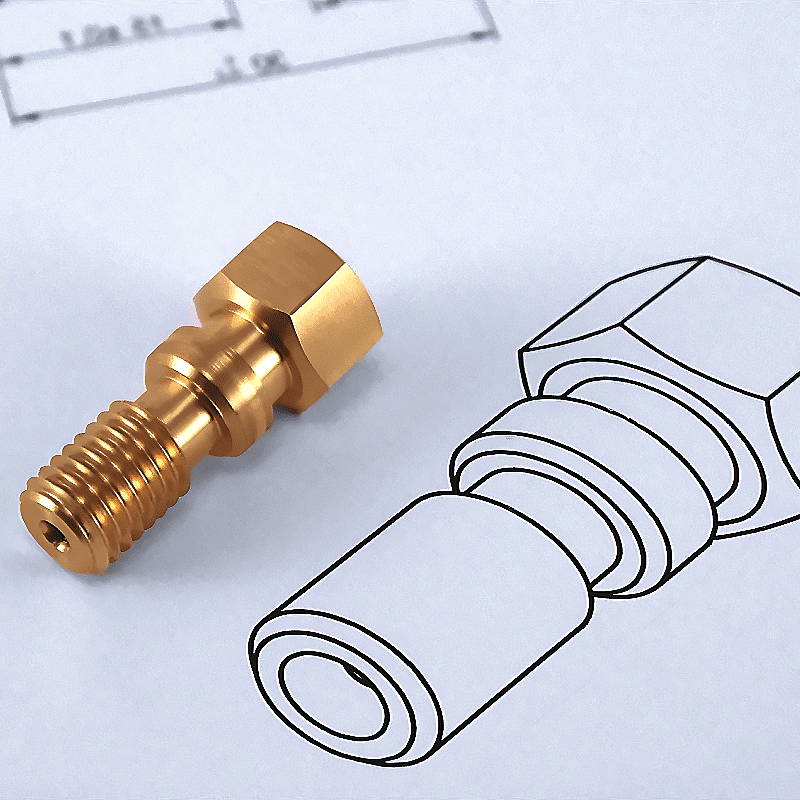

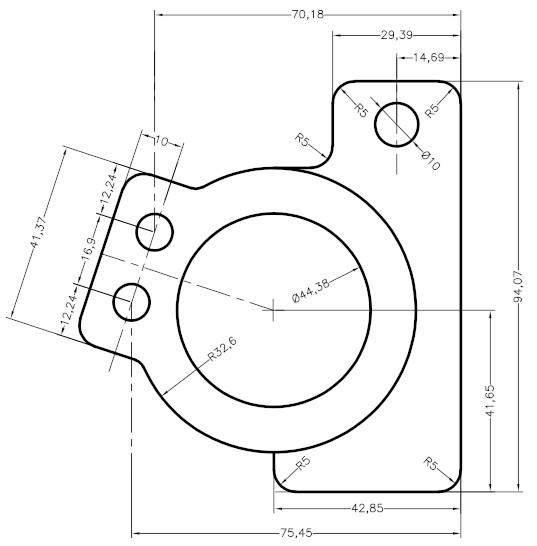

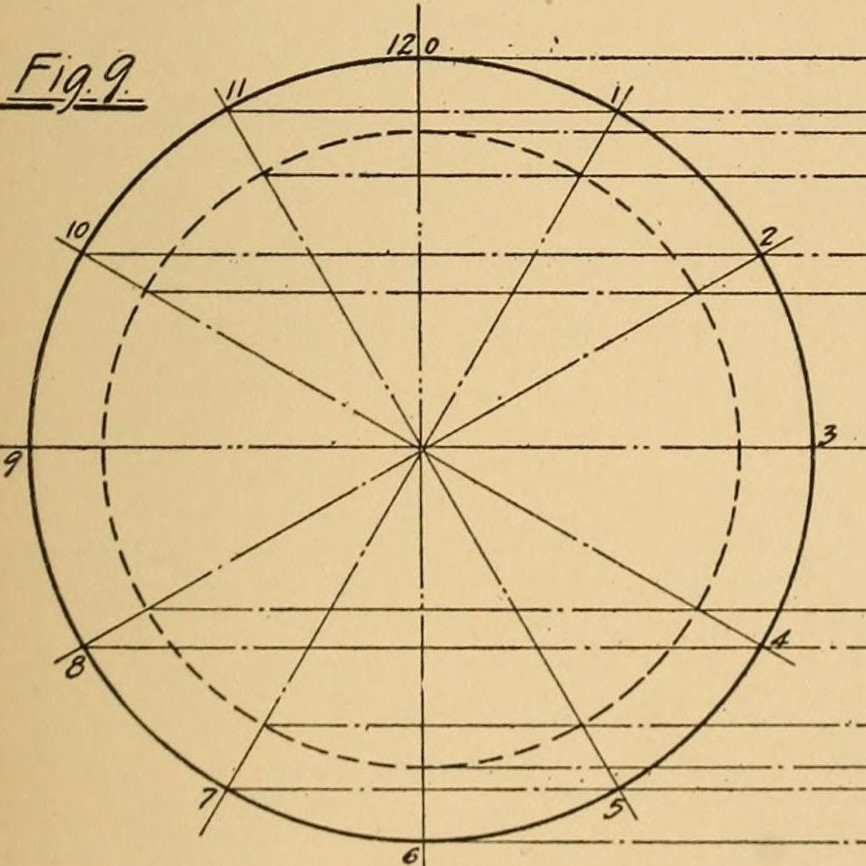

His career breakthrough came in 1765 when he was given the task of designing a plan for a fortification, which was to provide maximum protection against enemy fire, regardless of the enemy’s position. Traditional techniques for solving this problem required tedious mathematical calculations, but Monge proposed a new method based on rectangular projections and graphical representation of solids. His method was so innovative and effective that it was initially met with disbelief. As he himself recalled: “The simplicity of my approach caused suspicion, but the accuracy of the results quickly dispelled any doubts.” At this time, descriptive geometry was born – a discipline that allows three-dimensional objects to be accurately represented on a two-dimensional surface.

The success of this method brought Monge recognition at the École Royale du Génie, where he was soon promoted to professor of mathematics and physics. His innovative approach to teaching geometry was based on the practical application of rectangular projections and spatial analysis. In 1771, Monge published his first scientific paper on spatial curves and expandable surfaces, opening the door to Paris’s academia. With the support of such scientific luminaries as d’Alembert and Condorcet, Monge established a relationship with the Academy of Sciences and began a series of publications that established him as one of France’s leading mathematicians.

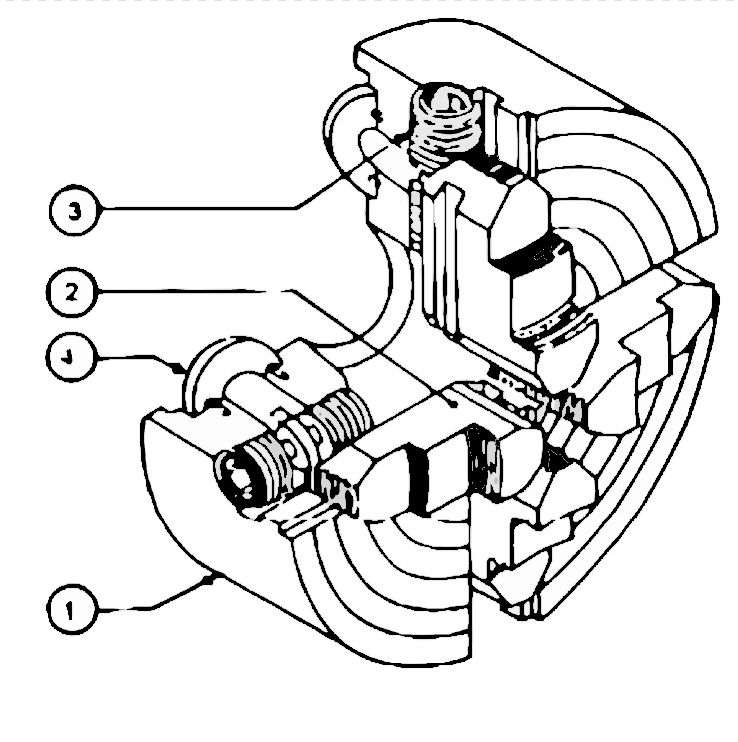

The development of the principles of draughtsman geometry came in the 1770s when Monge began to systematize his methods and demonstrate their application to engineering, architecture, and the military. Using basic elements such as rectangular projections on two planes, he created a set of rules that allowed precise representation of solids, calculation of their properties, and analysis of their interrelationships. This innovative discipline gained great recognition because it made it possible to design technical objects quickly and accurately, which was crucial in an era of intensive development of infrastructure and technology.

One of Monge’s most outstanding achievements was the development of the principles of polyhedral projections and spatial curves, which were widely used in military engineering. His method made it possible to optimize projects such as fortifications, bridges, es, and machinery, which directly impacted the development of infrastructure in France. In his publications, Monge emphasized: “Descriptive geometry is not just a mathematical tool, but a universal language of engineering that combines science and practice.”

However, Monge did not limit himself to descriptive geometry. His interests also included differential geometry and surface theory, which led to new discoveries in curvature analysis and the applications of differential equations to describe spatial shapes. Through his interdisciplinary work, Gaspard Monge became a pioneer of modern applied mathematics, and his work was fundamental to the development of science and technology in the 19th century.

Activities during the French Revolution

The French Revolution was a turning point in Gaspard Monge’s life as a scientist and citizen. During the tumultuous socio-political changes, Mong, as an ardent supporter of revolutionary ideals, devoted his skills and knowledge to the young republic. His involvement ranged from educational reform efforts to direct military support, making him one of the key figures of revolutionary France.

In 1792, Monge was appointed Minister of the Navy, recognizing his organizational and scientific skills. In this position, he was responsible for improving the production of armaments for the French Navy and organizing war logistics. One of his greatest achievements was writing the manual “Description de l’art de fabriquer les canons,” which described the process of producing artillery guns in detail. Monge not only coordinated this work but personally supervised the armaments factories, a unique combination of his scientific knowledge and practical involvement. During that period, he recalled, he worked almost tirelessly, trying to provide the republic with the necessary resources to fight numerous external and internal enemies.

At the same time, Monge played a key role in the Weights and Measures Committee, which introduced the revolutionary metric system – one of the greatest scientific achievements of the era. This was a step to simplify and standardize units of measurement throughout France, which was of great importance for both science and commerce. Together with other scholars, such as Pierre-Simon Laplace and Joseph-Louis Lagrange, Monge worked to precisely define new units, such as the meter and kilogram. The introduction of the metric system was not only a technical achievement but also a symbol of the revolutionary idea of equality and universality.

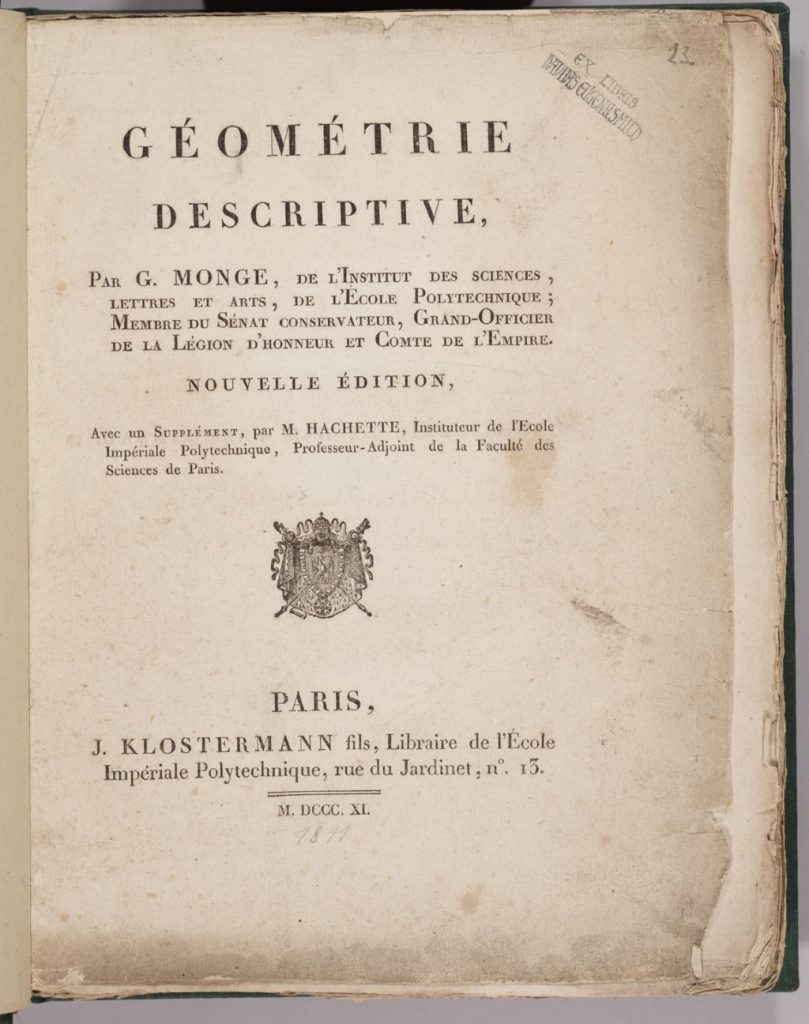

In parallel with his work in the administration, Monge was intensively involved in education reform, believing that the development of science and technology was the key to the future of the republic. He was one of the prime movers behind the creation of the École Polytechnique in 1794 – a school designed to train engineers and scientists capable of carrying out major technical projects for the modern state. Monge himself participated in the organization of the curriculum, placing particular emphasis on descriptive geometry, which he considered an essential tool for any engineer. His lectures, later published as “Géométrie descriptive,” became a textbook that revolutionized the teaching of this area of mathematics.

Monge was not only a teacher but also a mentor who inspired his students to take on new challenges and broaden their horizons. As one of his students recalled: “Monge taught not only drawing and calculations, but also how to think in space – he showed how to see the world through the eyes of an engineer.” His commitment to the development of technical education went far beyond the École Polytechnique program – Monge also supported the establishment of other educational institutions, such as the École Normale, whose goal was to train teachers for secondary schools.

Gaspard Monge’s activities during the French Revolution exemplify a remarkable combination of science, politics, and passion. His work on behalf of the republic contributed to France’s technical and educational development and demonstrated the enormous role that scientists can play in shaping society. Monge will forever remain a symbol of the scientific revolution that accompanied the political revolution.

Collaboration with Napoleon

In addition to his scientific work and involvement in the French Revolution, Gaspard Monge played an important role in the Napoleonic era. His close collaboration with Napoleon Bonaparte began during the campaign in Italy in 1796-1797. As a member of the Commission of Sciences and Arts, Monge accompanied the Napoleonic army, helping select works of art and artifacts to be transported to France. This was the time when Monge established a close relationship with Napoleon, which was based on mutual respect and admiration. Napoleon appreciated Monge’s knowledge, practicality, and commitment, and he often entrusted him with responsible tasks that required scientific precision and organizational ability.

However, Monge’s greatest challenge was the expedition to Egypt in 1798. Driven by both military and scientific ambitions, Napoleon took with him not only an army but also a group of scientists known as “savants,” which included Monge. The expedition aimed not only to conquer territories but also to study Egypt’s history, geography, and culture. Serving as president of the Egyptian Institute, Monge played a key role in organizing the scientific work. This institute, modeled on the Paris-based National Institute, was dedicated to documenting Egyptian monuments, studying flora and fauna, and solving engineering problems such as irrigation systems for the Nile Valley.

While in Egypt, Monge drew attention to the phenomenon of desert mirages, which fascinated both scientists and soldiers. Mirages, which gave the impression of distant bodies of water on hot sand, were mysterious to many. Using his knowledge of optics and physics, Monge was the first to provide a scientific explanation for the phenomenon.

He noted that mirages are the result of light refraction in layers of air at different temperatures, which creates the illusion of water. He wrote in his report: “Desert mirages are not magic, but a triumph of physics – proof of how nature plays with the senses through the laws of light.” His research was published in Mémoires sur l’Égypte and became one of the first scientific reports devoted to the phenomenon.

In addition to his optical research, Monge also participated in analyzing ancient Egyptian technologies and construction methods. He was enthralled by the monumentality and precision of the pyramids, which inspired his thinking about the role of geometry in architecture. At the same time, his organizational skills supported military and scientific logistics, ensuring that scientific research was carried out even under difficult wartime conditions.

Monge left Egypt with Napoleon in 1799, returning to France after the campaign’s fall. Back home, he continued to work with Napoleon, taking up the post of director of the École Polytechnique and overseeing the publication of scientific results collected during the Egyptian expedition. Although the expedition was militarily unsuccessful, its scientific significance was immense, and Monge went down in history as one of its key participants. His research and achievements in Egypt demonstrate not only the versatility of his mind but also his ability to combine science with the practical needs of expedition and exploration.

Last years of life

After returning from the Egyptian expedition, Gaspard Monge continued his scientific and teaching work. As director of the École Polytechnique, he was passionately committed to training future engineers and scientists. His lectures on descriptive geometry and mathematical analysis were widely appreciated, and his publications, such as “Application de l’analyse à la géométrie” (1807), contributed to the further development of differential geometry and applied mathematics. Monge was a dedicated teacher who not only imparted knowledge but also inspired his students to think independently and innovate.

However, Monge’s life changed dramatically after Napoleon’s defeat in 1815. As one of Napoleon’s closest collaborators, he became a target of repression by the new regime. He lost his posts, titles, and membership in the French Institute. The authorities considered him too closely associated with the fallen emperor, and his republican views made him persona non grata in the monarchist system. Overnight, Monge found himself on the margins of public life, deprived of the influence and recognition he had earned through his work.

He spent the last years of his life in solitude and poverty. Although he still tried to engage in scientific activities, limited opportunities, and his deteriorating health prevented him from being fully involved. Nevertheless, he remained true to his ideals, never backing down from expressing his republican beliefs, which deepened his isolation. He died on July 28, 1818, in Paris, abandoned by most of his former colleagues but surrounded by the affection and gratitude of his students.

Monge’s funeral at Père-Lachaise Cemetery became a symbolic tribute from his students and supporters, who, despite pressure from the authorities, attended in large numbers. His life, marked by outstanding scientific achievements and deep social commitment, was not forgotten. In 1989, on the bicentennial of the French Revolution, Monge’s remains were ceremoniously transferred to the Pantheon in Paris – where France’s greatest national heroes rest.

Monge was also honored in the Eiffel Tower, where his name was among the 72 names of France’s greatest scholars. A monument commemorating his life and achievements has been erected in his hometown of Beaune, and his scientific works continue to be cited and studied by generations of scholars. Monge remains a symbol of the combination of scientific genius and a steadfast commitment to building a better society. His legacy, in both mathematics and technical education, lives on today, reminding us of the role science can play in shaping the world.

Gaspard Monge – a summary of his achievements

Gaspard Monge was a unique figure who harmoniously combined scientific insight with a deep commitment to social and political issues. His work on descriptive geometry not only revolutionized the way three-dimensional objects are represented but also became the foundation of modern engineering and technical design. Thanks to his methods, it became possible to accurately design buildings, machines, and systems, which was crucial in an era of rapid technological development.

Monge did not limit himself to mathematics. His contribution to educational reform, particularly in the creation of the École Polytechnique, made the institution a model of modern technical teaching. He taught students knowledge and the ability to solve practical problems and think in space, which was crucial to their future careers as engineers and scientists. Through his involvement in the Committee on Weights and Measures, he also contributed to the introduction of the metric system, which is still the foundation of science and commerce today.

His work during the French Revolution and cooperation with Napoleon showed that a scientist could also be a citizen dedicated to his homeland. Monge combined science with practice, contributing both to the development of military technology and to the preservation of cultural heritage, as during his expedition to Egypt. His studies of mirages and ancient construction techniques show the versatility of his mind and his curiosity about the world.

Although the last years of Monge’s life were difficult, and political repression robbed him of the recognition he deserved, his legacy has stood the test of time. Gaspard Monge’s legacy is a reminder of how great a role science and education play in shaping societies. His life is a testament to the fact that knowledge can be used to both solve technical problems and build a more just world. Monge remains an inspiration to scientists and engineers, demonstrating that passion, innovation, and social commitment can go hand in hand to create a lasting foundation for the future.